The SNP’s record in Scotland: how does it stack up?

The SNP has been in power in Scotland since 2007, and the country is going to the polls again. So how has it performed?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What does Scotland’s government spend?

Spending on services that are largely devolved came to to £41.6bn in 2019-2020, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. This includes the vast majority of Scottish public spending on health, education, social care, transport, public order and safety, environmental and rural affairs, and housing. The IFS calculates that this equates to £7,612 per person in Scotland, which is an astonishing 27% higher than the £5,971 per person spent on those areas in England, and 13% higher than the £6,748 spent in Wales (where the population is older, poorer and sicker than in Scotland). Since 2007, the party spending that money has been the Scottish National Party, either as a minority government or, from 2011 to 2016, with an overall majority at Holyrood.

How has the SNP performed?

In its manifesto for next week’s Scottish election, the SNP trumpets its biggest achievements as “transforming education”, strengthening the NHS, creating a new social-security system with “game-changing benefits” and building thousands of affordable homes. The party boasts of creating a “fairer” country with a more progressive tax system, and delivering the “best public services” in the UK. The SNP has certainly spent heavily – in particular on subsidised childcare, early learning, enhanced child benefits and university tuition – but Scotland’s performance on a wide range of social indicators remains dire.

How dire?

Healthy life expectancy (HLE; the number of years lived in “good” or “very good” general health) is the lowest in Europe, at 61.8 years compared with an average of 68.3. Inequality is high: there’s a vast 25-year gap in HLE between the most- and least-deprived areas. Overall life expectancy is two years lower in Scotland than in the UK as a whole. Rates of poverty (including child, in-work and pensioner poverty) have all risen under the SNP. But the SNP’s most glaring failures concern its drugs deaths and (despite its boasts) its abysmal record on education.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What’s the story on drugs?

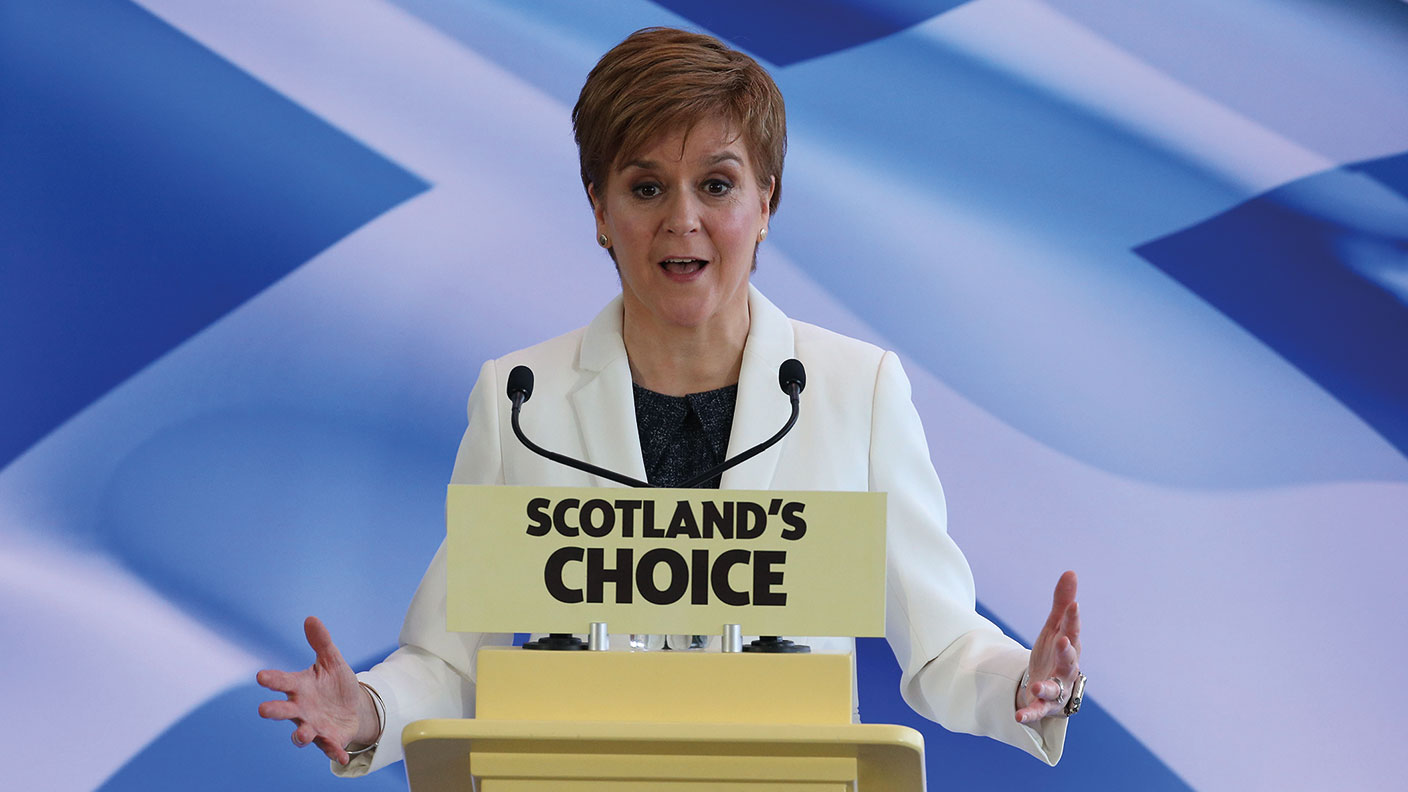

In 2019, 1,264 people died drug-related deaths in Scotland, more than twice as many as five years earlier – and the sixth year in a row to hit a new record high. According to The Economist, Scotland’s drug-death rate per person is now more than three times that in the rest of the UK, ten times the European average – and is probably higher even than in the US, a country ravaged by an opioid epidemic. The median age of those dying has risen from 28 to 42 over the past two decades – suggesting a close link with entrenched social deprivation – and 94% of all drug-related deaths involve people who took more than one substance. Heroin and morphine were implicated in more than half of the total, and “street” benzodiazepines were named in almost two-thirds of deaths, more than in any previous year. In December, after the long-delayed publication of the latest figures, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon called them “indefensible”, admitted her government had taken its “eye off the ball”, and sacked her public health minister. A shocking one in five Scottish adults are on anti-depressants; one in three on a range of drugs for sleep, depression or pain relief.

And education?

At the 2016 election Sturgeon made improving education the “defining mission” of her government, explicitly telling voters that narrowing the poverty-related attainment gap between well-off and poor pupils was the issue she “wanted to be judged on”. But last month the watchdog Audit Scotland found that the gap “remains wide” and progress towards closing it slow. Under the SNP Scotland’s once-proud education system has seen a near-constant slide down the PISA assessments comparing global educational attainment standards. It now ranks lower than England, and lower or alongside many much less wealthy countries. In 2010, the then First Minister Alex Salmond withdrew Scotland from two other international measures of maths, science and literacy, making such comparisons harder. And in 2017 the Sturgeon government scrapped the long-standing Scottish Survey of Literacy and Numeracy, making it harder to track the decline in both. It’s an odd way of delivering on your most critical mission.

How are public finances under the SNP?

Even before Covid-19, they were shaky. According to the most recent official data, published in August 2020, Scotland had a notional budget deficit of 8.6% of GDP in 2019-2020. That compares with 2.5% for the UK as a whole. In cash terms Scotland’s deficit was estimated to be £15.1bn. And that’s “just an appetiser” for what followed the pandemic, says David Smith in The Sunday Times. According to IFS projections, the 2020-2021 Scottish deficit (ie, for the fiscal year just ended) was 22%-25% of GDP – a peacetime record high. That compares with 14.5% for the UK as a whole, or around 16% including expected future write-offs on coronavirus loans. In cash terms, Scotland’s deficit will have been “comfortably more than £40bn”.

Why does that matter?

Fiscal instability matters in terms of Scotland’s future economic performance, and it also affects the prospects for independence and rejoining the EU. The UK budget deficit is projected to fall to around 3% of GDP over the next five years and historic data suggest its deficit will remain in, or close to, double digits for the foreseeable future. That would appear to rule out EU membership, a condition of which is sustainable public finances including (normally) a deficit of 3% of less. Scotland hasn’t had that for two decades. Scotland under the SNP doesn’t look it is actually preparing for independence. Rather, its high public spending and low tax revenues, compared with the UK as a whole, suggest its high degree of fiscal dependence on the rest of the UK is set to continue.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?