Coronavirus: Big Brother widens his embrace

The coronavirus crisis has led to a massive expansion of the state into all areas of daily life. Should we be worried?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What has happened?

In countries all over the world the scale of state interventions and the scope of state powers are growing fast in the wake of the Covid-19 emergency. In some places, this has been sinister: in Hungary, Viktor Orbán has seized full control of the state with powers that enable him to rule by decree indefinitely. In some countries, it has been chaotic and deadly: millions of impoverished city-dwellers are on the march in locked-down India, scrambling to survive the crisis in their home villages in the biggest exodus since partition.

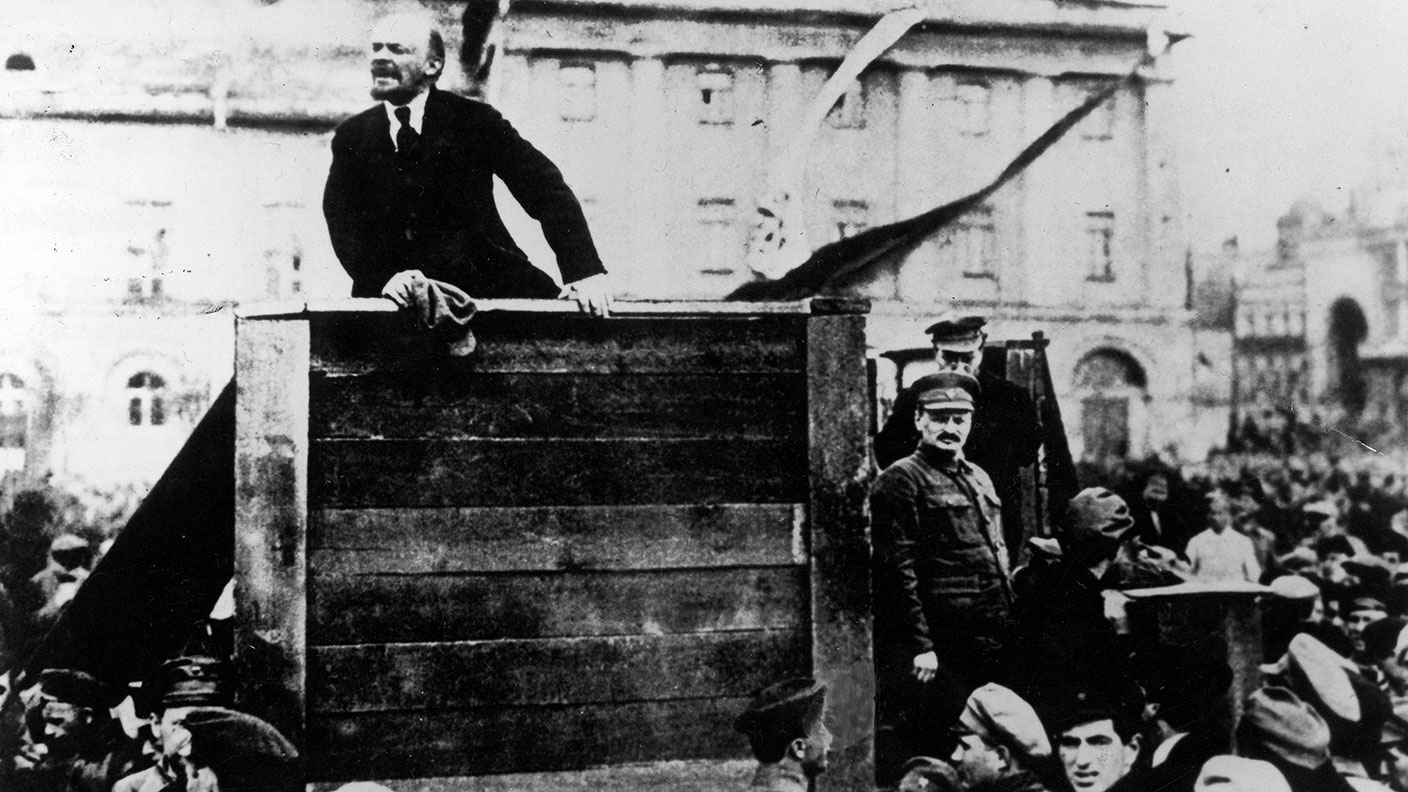

Never has Lenin’s famous maxim seemed more true: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” It is not an academic question as to whether the conditions for great social upheavals are being sown by the current crisis. The signs from Italy, where the sound of singing from balconies has faded and unrest has begun in the impoverished south, do not augur well.

Isn’t all this over-egging it a bit?

Not necessarily. Stable democracies such as Britain may not be on the brink of revolution, but nor is it likely that the rapid assumption of emergency powers – and the expansion of the state – will have no lasting effects.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In recent weeks, Western governments have promised trillions of pounds of public money to keep their economies on life support. In the US, the package amounts to 10% of GDP, twice what was promised during the 2007-2009 financial crisis. Credit guarantees in the UK and France amount to 15% of GDP. “For a while, at least, governments are seeking to ban bankruptcy,” says The Economist – and central banks are printing money to buy up assets they used to spurn.

All told, it’s the “most dramatic extension of state power” since World War II. In the past week, in the UK alone the government created £200bn to stave off a run on its bonds; announced that it would pay the wages of most self-employed people (as well as the employed); quietly renationalised the railways and ordered the population to stay indoors – conceivably for months rather than weeks.

But emergency action is needed, isn’t it?

Yes, but there’s a fiery debate brewing – certain to get more heated in coming weeks – about the tensions between individual liberties and state powers. Why were police officers shaming dog-walkers in the Peak District when London Underground carriages remained packed? Who has the power to define “essential” travel to help a “vulnerable” person?

The eminent jurist Lord Sumption, not known for hyperbolic excess, argues that the UK under our current lockdown-by-consent has quietly become a police state: “a state in which the government can issue orders or express preferences with no legal authority and the police will enforce ministers’ wishes”.

There is a separate but related debate emerging about the state’s role in “bio-surveillance” as a means of easing lockdowns while avoiding a second wave of viral infections.

Aren’t all these measures temporary?

Milton Friedman once acidly observed that “nothing is as permanent as a temporary government programme”. It is broadly agreed by modern historians that wars and other profound social crises tend to increase the size of the state and the scope of its functions. The growing fiscal reach of European states from the 1600s onwards, for example, was driven by the need to fight increasingly complex and far-flung wars.

Famously, Great Britain first introduced an income tax in 1799 as “a temporary measure necessary for the prosecution of the war” against Napoleon. The rate started at 1% on annual incomes of £60, rising to 10% on incomes above £200; rates have risen since then. France had no income tax in 1914; by 1919 the top rate was 50%. In Australia, direct federal taxation began in 1915, in Canada in 1916. In the US, the number of taxpayers liable for income tax grew from seven million in 1940 to 42 million in 1945, and so on.

Won’t the state shrink back again?

It might not. In Britain, and much of Europe, the vast expansion of the 1940s wartime state paved the way for the post-war welfare state, nationalisations and the massive long-run increases in taxes and spending lasting to the 1970s. More broadly, since 1900 UK government expenditure has risen from well under 10% of GDP to touching 40%.

All governments appear to find it easier to raise spending than to cut it again. Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak may not be natural “big state” enthusiasts, but they will find that it is easier to give guarantees to businesses, and grants to workers, than to withdraw them. The “novel notion that the government needs to preserve firms, jobs and workers’ incomes at any cost may endure” well beyond the crisis, argues The Economist.

So the government is making a mistake?

The point is more that the economic and political consequences could be seismic. Take, for example, the decision to pay 80% of “furloughed” workers’ wages on behalf of their employers. Obviously, this has a massive direct cost.

But it will also have a longer-term indirect cost by keeping unviable firms alive and thus encouraging the misallocation of resources. “Technology causes a certain churn in any employment market,” argues Daniel Hannan in The Daily Telegraph. “There are fewer secretaries, video-rental employees and local journalists than there were 15 years ago, but more people working in biotech, 3D printing and online gaming.”

By failing to discriminate between viable and near-obsolete companies and sectors, the massive state underwriting of businesses will damage this entirely normal process of creative destruction – a necessary feature of all capitalist economies. That’s just one example of how the government’s emergency decisions will have long-term effects. But it won’t be the only one.

Once the belief takes root that a magic money tree can be located in a crisis, many will wonder why it can’t be shaken more often.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.