Britain’s new immigration system

Free movement from the EU ends next year and Britain has taken back control of its borders. What will that mean in practical terms? And who benefits?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What has happened?

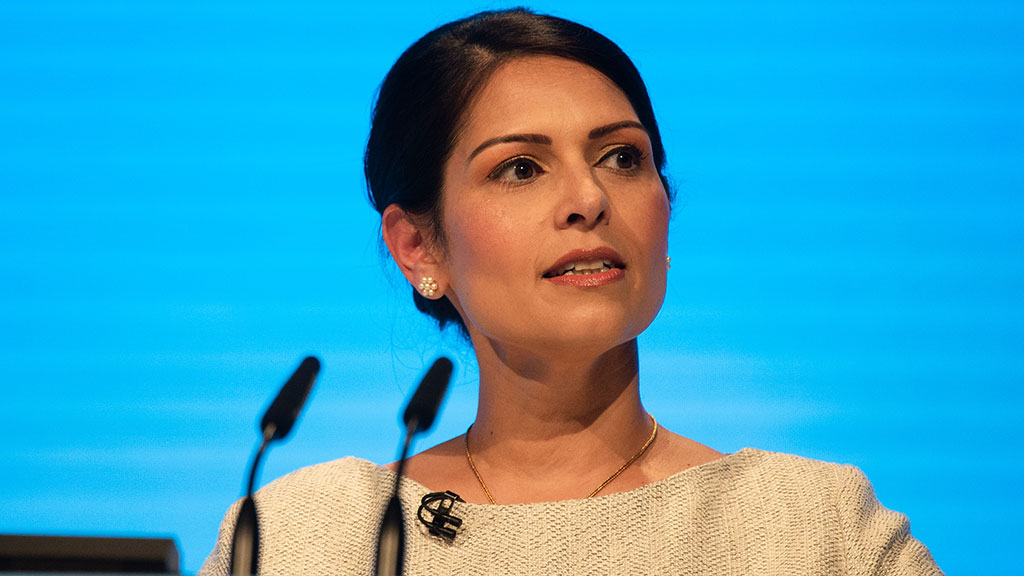

The government has announced details of its new “firm and fair points-based immigration system” that will take effect from 1 January 2021, when free movement between the UK and EU will end. The overall aim of the new system, according to the home secretary, Priti Patel, is to “take back control of our borders”, cut the overall level of immigration and move away from relying on “cheap labour” from Europe. Instead, the UK wants to “encourage people with the right talent” to move to the UK from all around the world with the underlying vision of creating a “high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economy”.

What are the details?

Although the scheme is branded as an Australian-style “points-based system”, the reality is more of a “blunt instrument”, says the Financial Times. To qualify for a work visa, applicants have to gain 70 points. But 50 of these are simply the “points” awarded for meeting three mandatory qualifications: speaking English; having a job offer from an “approved sponsor” before coming; and that job being above a “skills threshold” defined by the government.

To get the final 20 points, there are only two main routes: have a salary above £25,600; or have a job offer in a shortage occupation (as defined by the government’s advisory body on migration). Then there are exceptions for (presumably recent) PhDs who don’t yet earn £25,600: they can get the necessary 20 points if they have a PhD in a science-related field relevant to their job, or if they have a PhD in an unrelated field and earn more than £23,040. There’s no route in for lower-skilled workers, or the self-employed.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Will this cut immigration?

Not necessarily, because in important respects the changes mark a liberalisation of the rules, rather than a tightening. The UK’s damaging cap (of 20,000) on the number of skilled work visas has been scrapped. Applicants no longer have to have an undergraduate degree and be earning at least £30,000. Instead, an upper secondary qualification (equivalent to A-levels) and a job paying £25,600 will suffice.

And finally, the “Resident Labour Market Test” – which requires employers to advertise and try to fill vacancies domestically first – has also been dumped. So even though the Home Office estimates that 70% of the European Union citizens currently in the UK would not qualify under its new system, applicants from the rest of the world will find it easier.

What’s the reaction been?

On the whole, businesses are delighted with the overall loosening of the rules on recruiting overseas, but fearful about the effect of ending free movement for EU migrants who fill so-called low-skilled and unskilled jobs in the care sector, agriculture, construction, hospitality and food processing. At a time of near full-employment, cutting off a supply of mobile, flexible and relatively cheap labour is a gamble for the UK economy. The health sector will be protected by a separate “NHS visa”, but social care, where there are already tens of thousands of vacancies, is looking especially vulnerable. The government insists the existing 3.4 million EU citizens in the UK will help fill vacancies in hard-pressed sectors, but many in those industries are sceptical and worried.

Could “inactive” Britons fill the gaps?

Patel’s assertion that the new rules present an opportunity for 8.48 million “economically inactive” Britons aged 16-64 to join the workforce was met with scepticism. At 76.5%, the UK’s employment rate has never been higher. There are 800,000 unfilled vacancies and unemployment (3.8%) is at a 45-year low. According to official figures, 2.3 million of the “inactive” are students; 2.1 million are long-term sick or disabled; 1.9 million are caring for their families; 1.1 million are early retirees; and 160,000 are off-work due to temporary illness. That leaves 1.87 million who might be looking for a job.

Might they be tempted?

They might, says Philip Aldrick in The Times. The labour market is more fluid than ever, with hundreds of thousands of people moving in and out of it each quarter. The Centre for Cities think tank reckons that if you add the 1.1 million early retirees, plus the 700,000 who are either short-term sick or prefer not to work, plus various other kinds of “missing workers”, you are looking at as many as three million people.

If even a third of these could be tempted into work, it would more than offset the anticipated drop in immigration after Brexit – from around 250,000 a year to the official estimate of 165,000 a year – for a decade. “Which makes you think Ms Patel might have a point after all,” says Aldrick. If the government can offer the right policy nudges – more support for childcare and mental health, and flexible hours or a higher minimum wage to tempt the “retired” young – then “more inactives might move”.

Will all this boost productivity?

That’s the big question. Optimists point to Australia, Canada and New Zealand: all three operate a points-based immigration system and all have done better than the UK on improving productivity (and growing their economies) over the past decade. But the evidence of a causal link is disputed.

The UK government hopes that making it harder for low-paid sectors to rely on immigrant labour will force up wages and somehow “force” us to morph into a higher-skilled, higher-wage economy. But there’s no automatic relationship between higher wages and higher productivity, and the UK is facing a radical demographic challenge, which it is making more acute by ending low-skilled immigration.

The banal truth, says Bronwen Maddox in the FT, is that the new system is a politically driven gamble whose effects are “impossible to calculate”. As such, the government “would be well advised to build in” some wriggle room.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

No peace dividend in Trump's Ukraine plan

No peace dividend in Trump's Ukraine planOpinion An end to fighting in Ukraine will hurt defence shares in the short term, but the boom is likely to continue given US isolationism, says Matthew Lynn

-

Europe’s new single stock market is no panacea

Europe’s new single stock market is no panaceaOpinion It is hard to see how a single European stock exchange will fix anything. Friedrich Merz is trying his hand at a failed strategy, says Matthew Lynn

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

Britain’s inflation problem

Britain’s inflation problemInflation in the UK appears to be remaining higher for longer when compared with similar rich countries. Why? And when can we expect a return to normal? Simon Wilson reports.