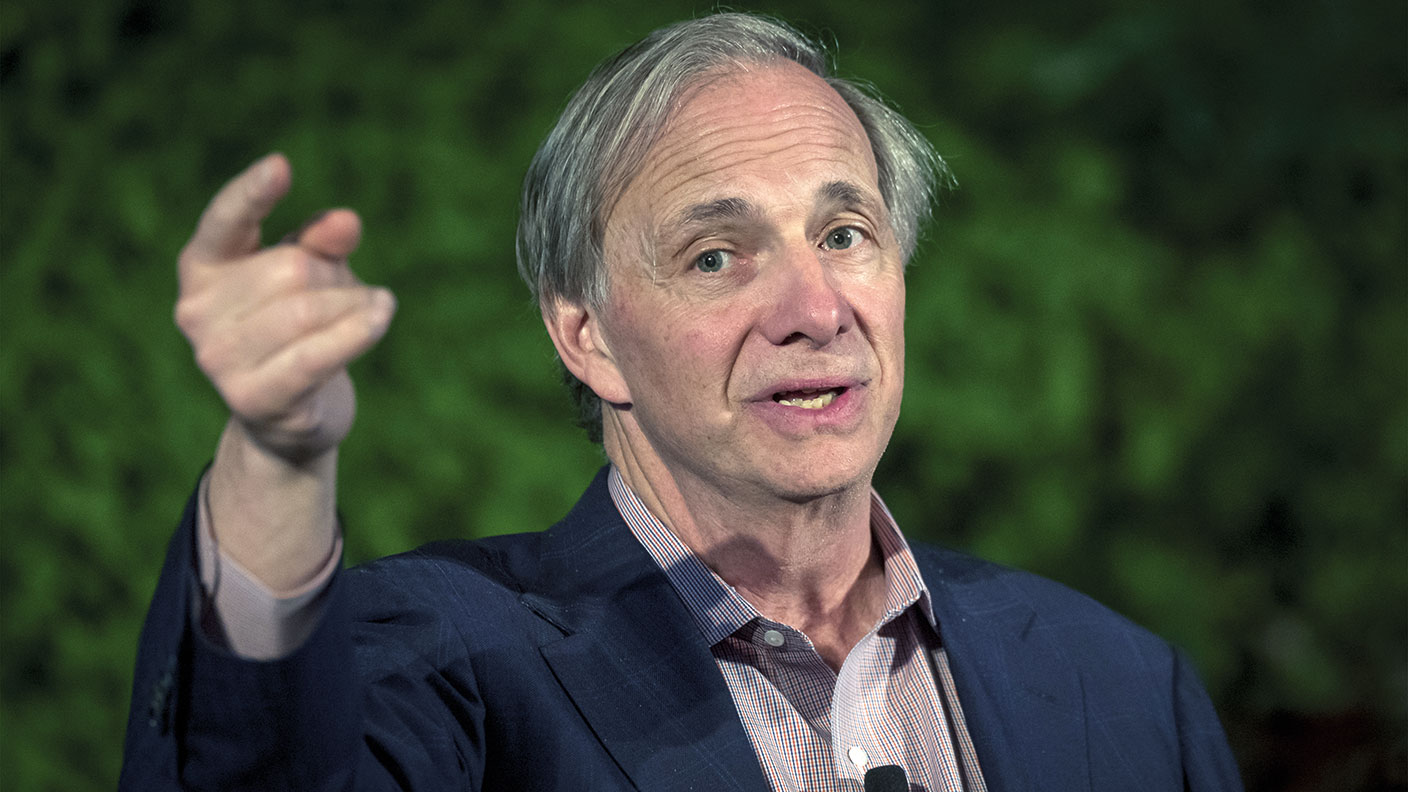

Ray Dalio: the seer blindsided by a bug

When the financial crisis struck in 2008, Ray Dalio’s hedge fund was well prepared to profit and he has since enjoyed a reputation for prescience. He was, he admits, not so fortunate this time round.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“It’s never easy to admit that you’re wrong, especially when you have previously earned fame (and billions of dollars) by calling the future right,” says Gillian Tett in the Financial Times. Yet Ray Dalio has done just that. The founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates, with a personal fortune previously estimated at £18bn, concedes he was badly wrong-footed by the coronavirus market turmoil – “in sharp contrast to the 2008 financial crisis, when he and his team predicted events with such prescience that they profited handsomely”. This time around, Dalio’s $160bn flagship fund is down by about 20% because, as he admits, Bridgewater’s analytic systems couldn’t “offer any guidance” about a rare event such as a pandemic.

A Young Turk humbled

Dalio will surely be taking it in his stride. A key story in Dalio’s best-selling book – part memoir, part how-to guide – tells of his meltdown in 1982, when a series of bad bets on bonds nearly imploded his fund, wrecking his reputation as a Young Turk of the markets, says The New York Times. “Being so wrong – and especially so publicly wrong – was incredibly humbling and cost me just about everything,” he writes. “I saw that I had been an arrogant jerk… betting everything on a depression that never came.” He had to let all his staff go and borrow from his father to pay his bills.

Ultimately, Dalio’s love of markets saw him through. It began at a young age in the early 1960s. Growing up in Long Island, the son of a jazz musician, he started investing at 12, getting tips from golfers for whom he caddied. The first stock he bought was Northeast Airlines. Thanks to “a lucky merger”, the young investor “tripled his money”, notes CNBC, and he was “hooked”. By the time he graduated from high-school, Dalio had built an impressive portfolio worth thousands. After a stint at Harvard Business School, Dalio headed for Wall Street, becoming a commodities trader at Shearson Hayden Stone. But he was “temperamental” and didn’t last long, says The Times. In 1974, he punched his boss at a party; shortly after he was fired. The following year, aged 26, he founded Bridgewater from his apartment in New York city.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Calmed by meditation

Aside from its performance (over four decades, the firm has made more money for its investors than any other hedge fund in history, according to Bloomberg), Bridgewater is best known for its unique culture, says The New York Times. Staff at his fund rate performance during meetings, scoring colleagues out of ten for open-mindedness, creativity and assertiveness and so on. Their overall rating is taken into account in investment decisions. Critics have likened this “social experiment” to Big Brother – there are horror stories about the “often brutal feedback” and turnover among new employees is high.

Still, Dalio claims to have overcome his own fiery tendencies by practising transcendental meditation. He says he is now far more interested in “the gorgeousness of nature, not the things you buy”. Based on the assumption that what he calls the “success” phase of his life is over, Dalio is no longer chasing personal glory – though doubtless recent setbacks will galvanise him to make good the fund’s losses. Confident that his legacy has been secured by the uptake of his principles, he says he now feels “free to live, and free to die”. Ommmmmm.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?Was the VICE bankruptcy inevitable? We look into how the once multibillion-dollar came crashing down.

-

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?Warren Buffett, sometimes referred to as the “Oracle of Omaha”, is considered one of the most successful investors of all time. How did he make his billions?

-

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory right

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory rightProfiles Kwasi Kwarteng, who studied 17th-century currency policy for his doctoral thesis, has always had a keen interest in economic crises. Now he is in one of his own making

-

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all away

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all awayProfiles Outdoor-equipment retailer Yvon Chouinard is the latest in a line of rich benefactors to shun personal aggrandisement in favour of worthy causes.

-

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goods

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goodsProfiles Johann Rupert, the presiding boss of Swiss luxury group Richemont, has seen off a challenge to his authority by a hedge fund. But his trials are not over yet.

-

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket king

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket kingProfiles Alvin Chau made a fortune catering for Chinese gamblers as the authorities turned a blind eye. Now he’s on trial for illegal cross-border gambling, fraud and money laundering.

-

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzy

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzyProfiles Ryan Cohen was credited with saving a clapped-out videogames retailer with little more than a knack for whipping up a social-media storm. But his latest intervention has backfired.

-

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest man

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest manProfiles India’s Gautam Adani started working life as an exporter and hit the big time when he moved into infrastructure. Political connections have been useful – but are a double-edged sword.