With the right political will, inflation can be defeated

Governments and central banks can easily control inflation, says Merryn Somerset Webb – they just need the will.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The latest numbers on UK inflation are out; the consumer price index is rising at 3.2% a year. That’s pretty nasty, but look to the US and you will see something nastier: there, prices are rising at 5.3%. We haven’t seen these kinds of numbers in the West for decades. You might think they aren’t much to worry about – the various economic distortions caused by the extraordinary policy response to Covid-19 were hardly going to just fade away, and the meeting of supply constraints with unlimited money printing was always going to have consequences – but it is perfectly reasonable to think they will work through the system and we will soon be back to our old mildly-disinflationary normal. This bout of inflation, our central bankers say, is “transitory.” Are they right?

The jury is obviously still out, but it is looking less transitory by the minute. In this week's magazine, Philip Pilkington argues that real long-term inflation is usually driven by labour shortages. We definitely have those: there are well over a million job vacancies in the UK. And it is no good trying to blame that on Brexit – there are labour shortages everywhere. In the US, there are ten million-plus job openings (many more than there are jobless people) – nearly four million more than pre-pandemic. Half of US small firms are hiring; of those, 60% say they can’t find qualified applicants. Around 50% are raising prices – presumably in part because they are having to raise wages to get staff. Explanations vary: school closures have forced parents to stay at home with kids; lifestyle preferences have changed; vaccination mandates have locked people out of career paths; and perhaps pandemic savings have allowed some to opt out of work or to retire early.

There is also, as Philip notes, fear: in the UK, 42% of people still say they are “very” or “somewhat” scared of catching Covid-19 (YouGov). How much might you have to pay someone scared to come to work, to come to work? How much might you have to pay someone who doesn’t want a vaccine to get one in order to work? And how much might you have to pay someone who has decided they are happy to forgo a lot of their pre-pandemic consumption habits in order to stay out of the labour market? Add this dynamic to ongoing supply disruption (it doesn’t seem to be working itself out in a hurry), and the fiscal stimulus still being offered by governments, and if I were forced to choose a word for today’s inflation, I might ditch “transitory” for “persistent.”

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The good news is that governments and central banks can easily control inflation: they can pull back from creating endless demand via vast public spending programmes financed by binge money-printing and they can raise interest rates. Inflation is then mostly a function of their policy decisions (or lack of). The bad news is that those decisions are really hard to make. Who wants to be the one who reneges on “build back better” promises, or who drives businesses into bankruptcy and homeowners into default with sharp rate rises? You need brave governments with eyes to the long-term greater good for that, and I’m not sure we have those.

This matters. According to the Financial Conduct Authority, 8.6 million people have more than £10,000 in cash savings. With interest rates stuck close to zero and inflation over 3%, those cash pots lose value every day – and are likely to continue to do so. They need protecting. How? Some of the answers are in this week's magazine.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

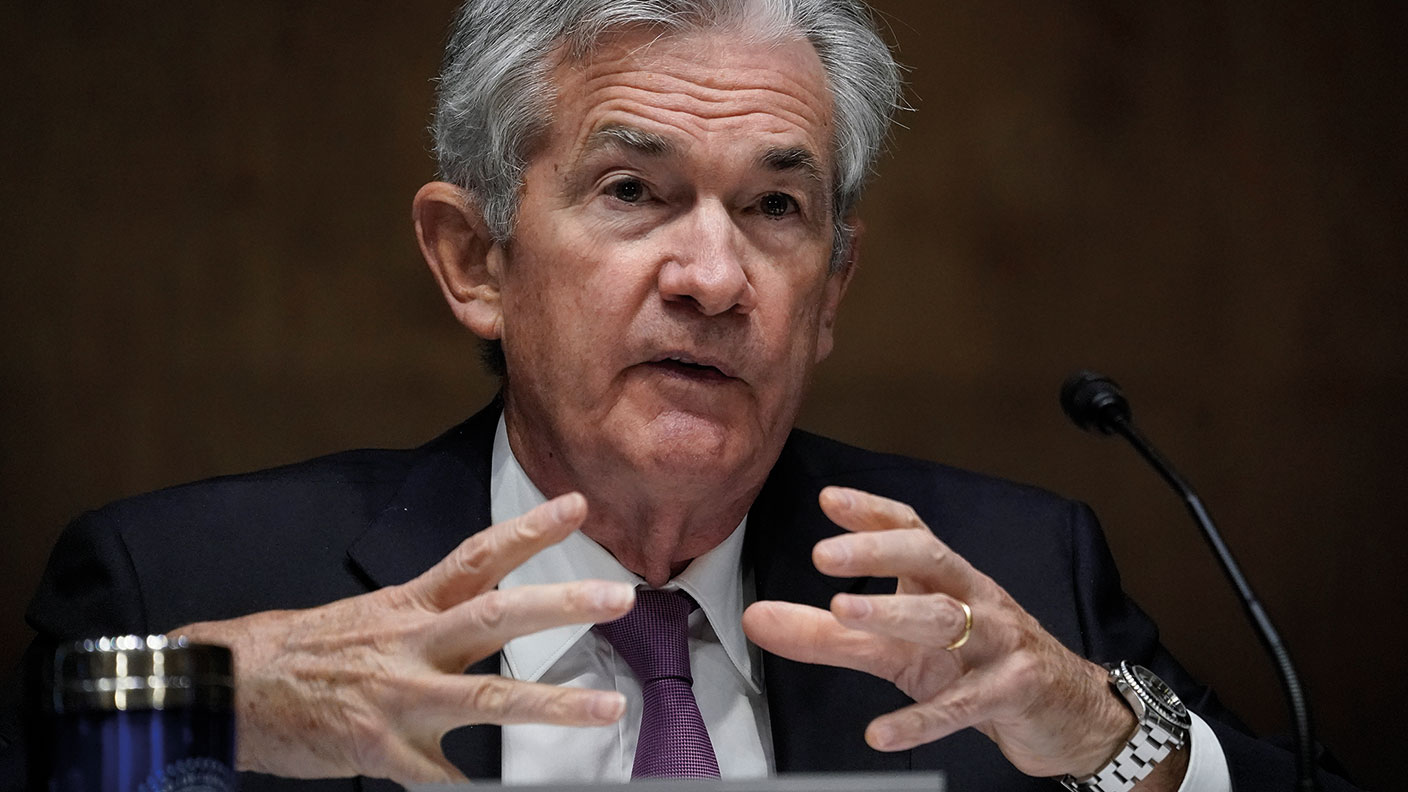

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn