The return of antimicrobial resistance – the silent pandemic

Before the advent of antibiotics, a small cut could be fatal, and surgery and childbirth were extremely hazardous. Is the rise of antimicrobial resistance sending us back to that era? Alex Rankine reports.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What’s happened?

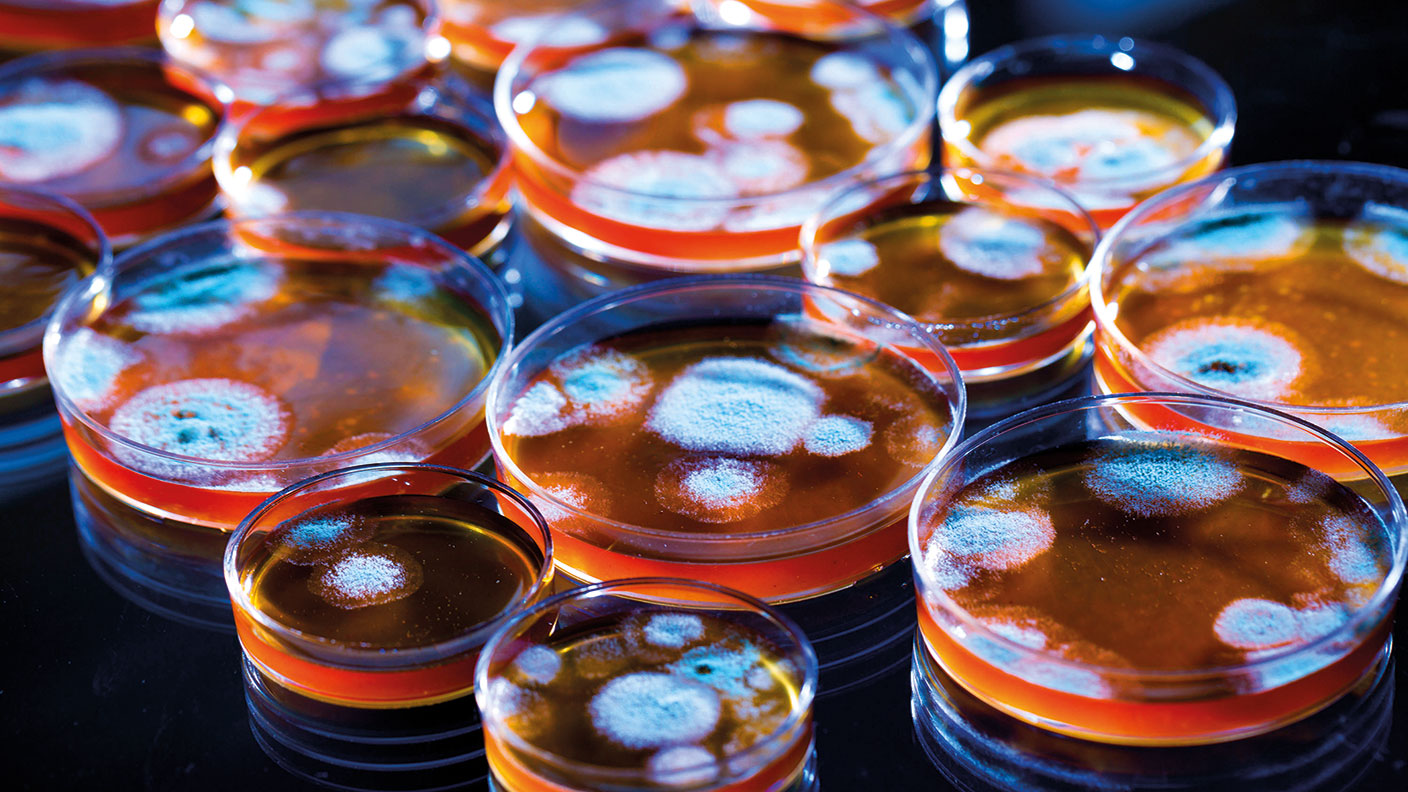

Humanity has had the upper hand in the battle against pathogens since Alexander Fleming’s discovery of the antibiotic penicillin, which fights bacteria, in 1928. Yet bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites are constantly evolving to evade the drugs we use to treat them. Some of these drug-resistant “superbugs” are well known: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a particular danger in hospitals. Strains of drug-resistant bacteria that cause tuberculosis kill hundreds of thousands each year. Globally, at least 700,000 people are thought to die every year of drug-resistant diseases. A report by the UN predicts that number could hit ten million come 2050 if no action is taken.

How do the bugs evade drugs?

Evolution by natural selection. Antimicrobial drugs create a strong selection pressure in favour of the survival of variants of the bugs that aren’t affected – because they produce enzymes that neutralise the drugs, for example, or have biological pumps that remove them from the cell. The problem has got worse as a result of overuse of antibiotics. Doctors have often overprescribed the drugs, even for ailments like colds against which they do nothing. The problem of overuse is acute in agriculture: healthy livestock in much of the world are routinely fed antibiotics to ward off infection and promote growth. That gives the pathogens billions of new opportunities to find ways around our treatments.

What are the consequences?

No new class of antibiotic has been found since the 1980s. As pathogens develop resistance to existing treatments, we are running out of options. Antimicrobial resistance has been dubbed the “silent pandemic”. The problem is likely to worsen, gradually but unrelentingly, killing ever more people as each year passes. In the future, a simple cut could prove fatal, as in the centuries before the discovery of effective antibiotics. Surgery and childbirth would become far more dangerous. Procedures like hip replacements might become too risky to countenance. “The standard treatment for tuberculosis before antibiotics used to be – fresh air,” says Toby Sealey for the BBC. The “post-antibiotic era” is not a place anyone wants to live.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What about the economy?

Widespread antimicrobial resistance could radically alter our lives – it is easy to forget just how much of modern life rests on effective antibiotics. Take risky sports.

People might be more cautious about going skiing, for instance, if an accident on the slopes carried a real risk of hospitalisation, infection and death. A review by the economist Jim O’Neill in 2016 found that the cumulative cost of antimicrobial resistance between 2015 and 2050 could hit $100trn if nothing is done. The World Bank estimates that annual global GDP would be 3.8% lower by then in a “high-impact scenario”. The O’Neill review found that it would cost the world $40bn over a decade to address the problem by fixing broken drug pipelines. Evidently, “this is tiny in comparison to the cost of inaction”.

Why don’t we do it then?

There is no money in saving the world. Take the case of US biotech business Achaogen, which developed a drug that treats superbug urinary tract infections. It couldn’t turn a profit and had to file for bankruptcy in 2019. “Bringing a drug from the laboratory to the clinic typically takes a decade and costs around $1bn,” says The Economist. The rewards are minimal. Pharmaceutical firms make money on volume. That is one of the reasons they invest so much cash into finding treatments for chronic conditions, which can be sold again and again. But we don’t want new antibiotics to be used regularly: they are humanity’s last line of defence, not a pill to be popped every day.

What is to be done?

Governments increasingly understand that they need to create better incentives for antibiotic development. O’Neill suggested giving firms cash prizes of up to $1.3bn for developing new treatments. This would cost a tiny fraction of total G20 healthcare spending. An alternative is dubbed the “Netflix model”. Healthcare providers would pay a subscription to receive antimicrobial drugs on demand, rather than paying per pill. The NHS is currently trialling a version of this idea, paying upfront for the development of two antibiotics according to their value to the service rather than the quantity bought.

Will technology solve the problem?

The World Health Organisation reports that there are 43 antibiotics in clinical development. Yet many of these are just small tweaks to existing drugs. None look likely to turn the tide against the 13 most-concerning superbugs. Yet humans are an ingenious bunch. One idea is to vaccinate vulnerable people against the most dangerous microbes. GlaxoSmithKline is working on jabs targeting priority pathogens. Perhaps even more promising is artificial intelligence, where scientists have made tremendous strides in recent years. Last year researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology reported that they had used a deep-learning algorithm to analyse 107 million molecules for anti-bacterial potential. They have already found one promising candidate, called halicin. Where finding new antibiotics was once a matter of happy accident, today the process proceeds at computer-enabled warp speed.

So it’s not all bad news then?

No, but all this innovation will be for nothing if humanity just overuses the new drugs in the same way as the old ones, causing the cycle of microbial resistance to repeat. But there has been progress: UK sales of antibiotics for use in food-producing animals are down 40% since 2014, but overuse elsewhere – especially in Asia – remains a pressing concern.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alex is an investment writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2015. He has been the magazine’s markets editor since 2019.

Alex has a passion for demystifying the often arcane world of finance for a general readership. While financial media tends to focus compulsively on the latest trend, the best opportunities can lie forgotten elsewhere.

He is especially interested in European equities – where his fluent French helps him to cover the continent’s largest bourse – and emerging markets, where his experience living in Beijing, and conversational Chinese, prove useful.

Hailing from Leeds, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Oxford. He also holds a Master of Public Health from the University of Manchester.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?