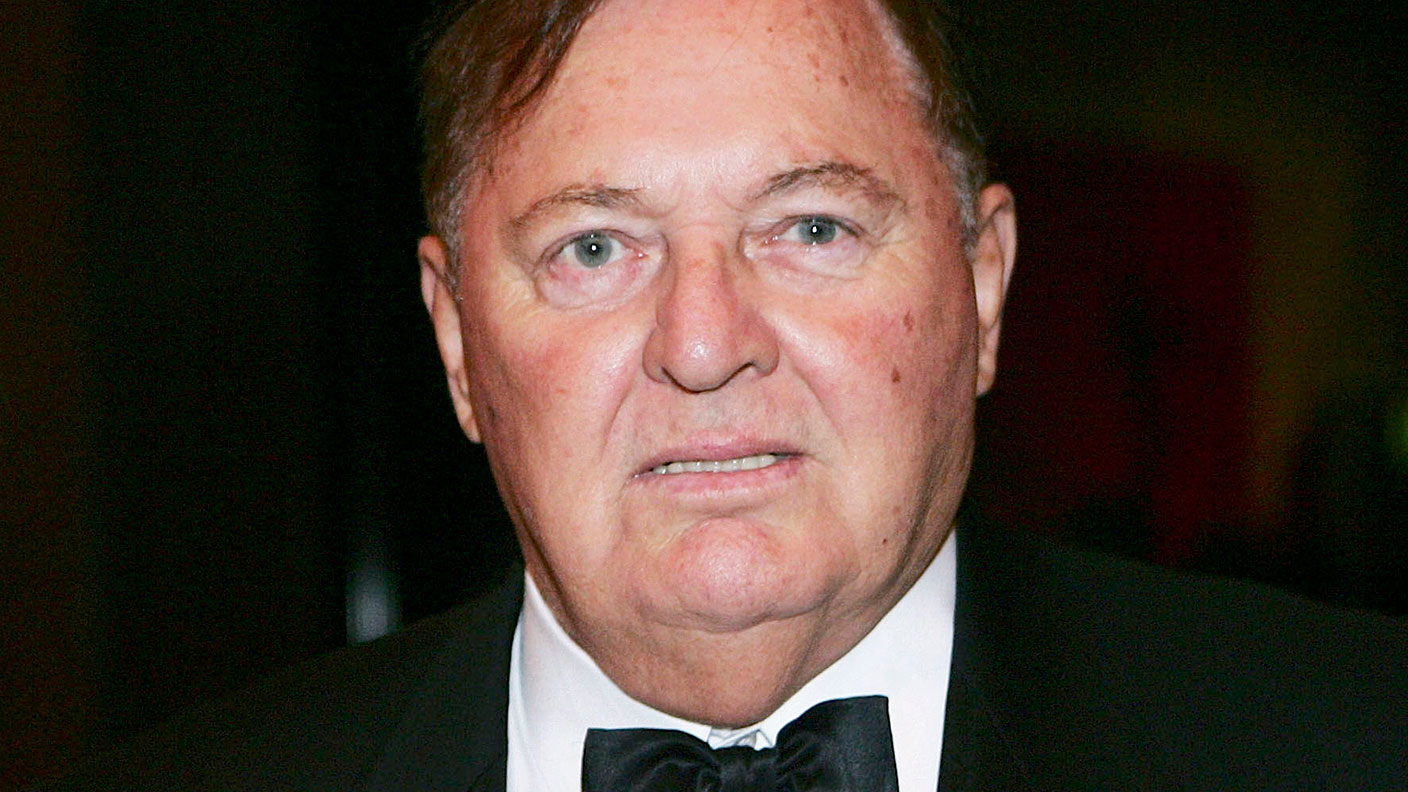

Great frauds in history: Takafumi Horie and Livedoor

Takafumi Horie used Enron-style dummy partnerships to inflate the revenue and operating profits of his company Livedoor.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

How did it begin?

Born in the city of Yame in 1972, Takafumi Horie studied at the University of Tokyo before dropping out to found Livin' on the Edge (renamed Livedoor in 2004), a web-services start-up that went public in 2000. Its rapidly-growing profits and soaring share price allowed it to go on series of acquisitions. Horie's talent for self-promotion and his willingness to engage in hostile takeovers won him an equal number of admirers and detractors. At its peak Livedoor employed 1,000 people and had a market capitalisation of $7bn.

What was the scam?

Livedoor's strategy of paying shares, rather than cash, for the firms that it bought, gave it an incentive to keep the share price as high as possible: the higher the share price rose, the bigger Livedoor's purchasing power. In order to keep Livedoor's share price rising, Livedoor resorted to accounting manipulation, using Enron-style dummy partnerships to inflate its revenue and operating profits. In 2003-2004 the effect of this manipulation transformed losses of 310m (£2.2m at current exchange rates) into supposed profits of 5bn (£35m). It also spread market rumours designed to boost the share price of listed subsidiaries.

What happened next?

Livedoor's bid for broadcaster Fuji in 2004 and Horie's bid for Japan's parliament in 2005 ruffled many feathers in the country's establishment and led to increased regulatory scrutiny of Livedoor. In January 2006, Livedoor's offices were raided by regulators and one of Livedoor's bankers committed suicide. Horie was arrested days later and Livedoor was delisted. Horie was convicted in 2007 of fraud and sentenced to two and a half years in jail. Fund manager Yoshiaki Murakami was imprisoned for taking advantage of insider tips from Horie about which firms he was going to try to buy.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Livedoor would eventually be sold to a Korean firm NDH in 2010 for only 6.3bn (£44.3m), a fraction of its peak value, although shareholders did get some additional money back from various lawsuits against both Livedoor and Horie himself. An acquisition spree, especially when the underlying company is barely breaking even, is a cause for concern, since companies may be tempted into manipulating accounts (as Livedoor did). Acquisitions can also be used by management to provide cover for any subsequent accounting irregularities that emer

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

Pensions vs savings accounts: which is better for building wealth?

Pensions vs savings accounts: which is better for building wealth?Savings accounts with inflation-beating interest rates are a safe place to grow your money, but could you get bigger gains by putting your cash into a pension?

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.