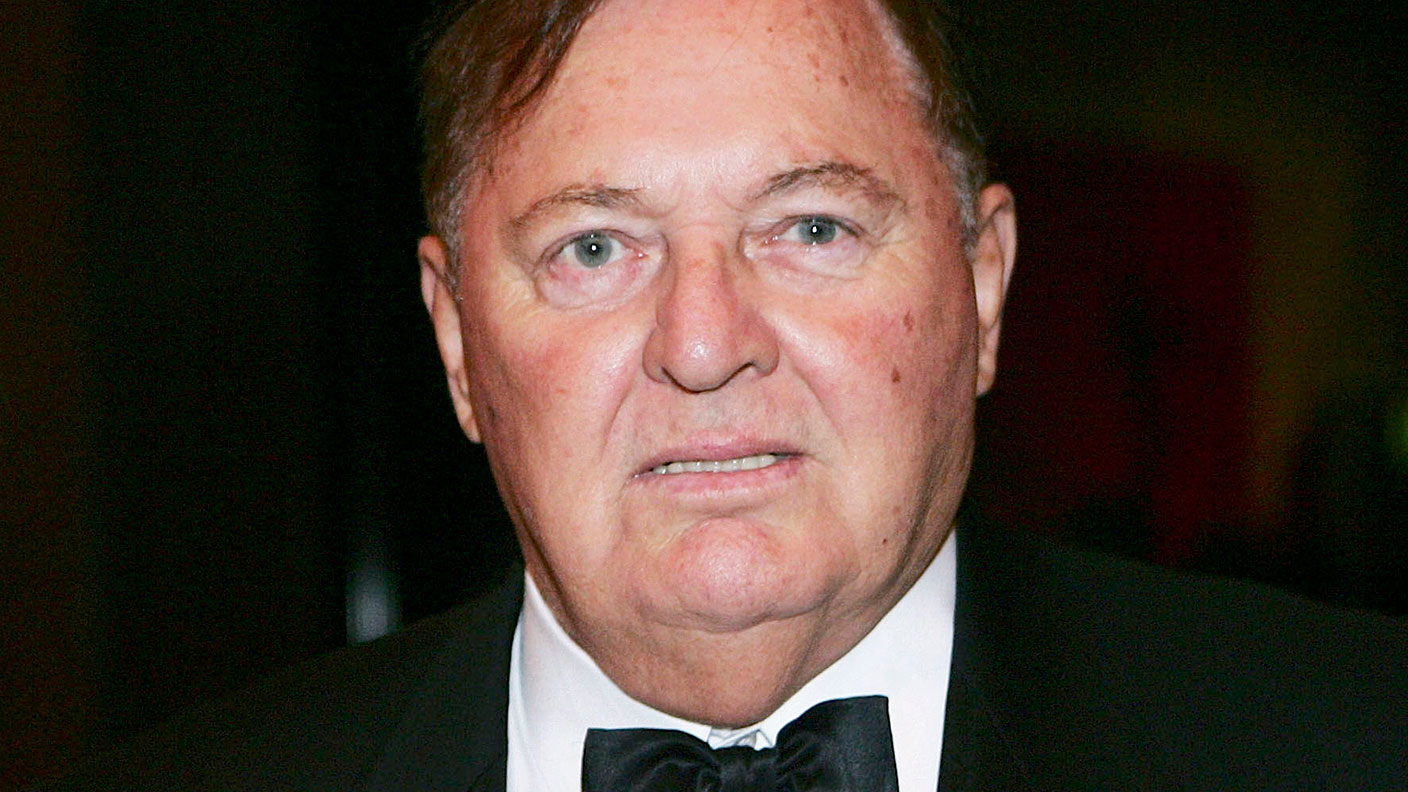

Great frauds in history: Albert Grant

Albert Grant made his money buying worthless companies and using fraud, hype and manipulation to sell them to the public at vastly inflated prices.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

How did it begin?

Born Abraham Gottheimer in Dublin in 1831, Albert Grant set up the Mercantile Discount Company in 1859, which failed two years later. In 1864 he set up a brokerage house, Crdit Foncier and Mobilier of England, which he used to promote various companies that he helped float on the stock exchange. By 1865 he was rich enough to own a large mansion in Surrey, get elected to parliament as MP for Kidderminster and buy Leicester Square as a gift to the public. He was also created an Italian baron in 1868.

What was the scam?

Albert Grant made his money buying worthless companies and using fraud, hype and manipulation to sell them to the public at vastly inflated prices. Perhaps his most notorious case was his involvement with the Emma Silver Mining Company in 1871, where he helped a consortium involving US senator William Stewart float a Utah mine on the stockmarket. As well as paying the distinguished geologist Benjamin Silliman $25,000 ($530,000 in 2018) to certify that it was "one of the great mines in the world", Grant even bribed the financial editor of The Times to let him write articles puffing the company under a pen name.

What happened next?

Despite scepticism from mining journals, the favourable coverage in newspapers and financial magazines, along with monthly dividends coming from silver that had been apparently been mined, propelled the value of the Emma Silver Mining Company to £5m (£457m today). However, in the summer of 1872, disaster struck when a manager claimed that a flood had shut down production and a rival was insisting that Emma's silver ore was in fact its own. While the company briefly limped along thanks to its dividends (funded by a loan from one of the directors) these were suspended and by 1873 the firm had collapsed.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Even counting dividends, shareholders only received a fraction of their investment back. Litigation would lead to the collapse of Grant's empire and his bankruptcy in 1877. By 1876 the value of the 37 companies that he floated had declined from £25.1m in 1872 to only £5.6m a loss of nearly £19.5m (£1.8bn in 2018). A major red flag that might have alerted investors was the promises of huge dividends, at one point equal to 80% of the original share price.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?With gold and silver prices having outperformed the stock markets last year, mining stocks can be an effective, if volatile, means of gaining exposure

-

8 ways the ‘sandwich generation’ can protect wealth

8 ways the ‘sandwich generation’ can protect wealthPeople squeezed between caring for ageing parents and adult children or younger grandchildren – known as the ‘sandwich generation’ – are at risk of neglecting their own financial planning. Here’s how to protect yourself and your loved ones’ wealth.

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.