How to profit as technology transforms the way we learn

Education and training could be a $10trn business by 2030. Innovations such as e-learning and digitisation will offer huge opportunities for investors to cash in on the boom, says Stephen Connolly.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Medical breakthroughs, new technology and the disruption of established industries have become part and parcel of daily business news. By comparison, education and training can seem much less exciting, despite being critical raw materials for innovation and advance. A dynamic, cutting-edge and productive global economy is a result of a highly skilled and educated workforce. And in the same way that businesses must become increasingly nimble and adaptable with products and services, so too must the process of training the workforce of the future.

Global workers, often facing significant financial vulnerability and inequality, can see that their knowledge and skills are a passport to career progression, higher incomes, and better living and working conditions. At the same time, businesses can't allow their employees' skills to fall behind those of competitors making corporate investment in training an imperative. These are powerful drivers: an individual's instinct to progress and a business manager's need to compete and succeed.

Serving them has helped to make education and training a significant industry with an attractive outlook. Spending on education was estimated at some $5trn (£4.1trn) in 2015 and is projected to double to $10trn by 2030, outpacing global economic growth, according to researchers HolonIQ. Witnessing the positive trends back in 2012, John Fallon, who had just taken over as chief executive of Pearson the global education and publishing business said that he thought education "would turn out to be the great growth industry of the 21st century".

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What education means for investors

Understanding how these changes could benefit investors requires a better appreciation of what education means. Unlike, say, the oil, mining and banking industries, there's no clear-cut sector of businesses involved in education. Furthermore, many people are used to thinking of education provision as largely a not-for-profit activity in the UK, for example, there are state and private schools, but the latter hold charitable or similar statuses and don't have shareholders. But of course, it's for-profit businesses that are of interest to investors. They're not new and their success differs depending on the education services they offer, but their presence and influence are growing as they emerge in new niches, or even disrupt established but outdated education practices.

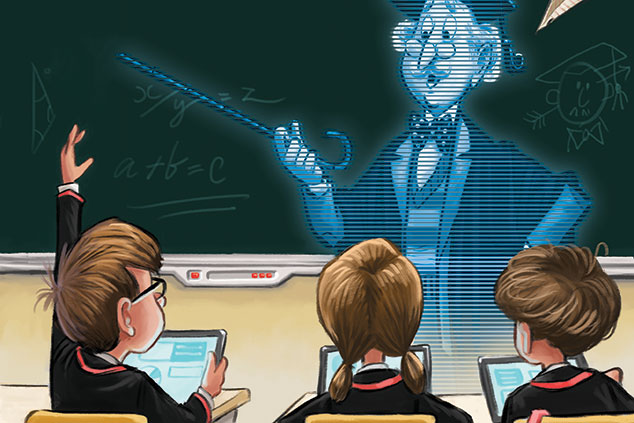

Think of global, borderless education emerging from an accelerating use of the still under-utilised internet; training delivered via the ubiquitous mobile phone; virtual reality applications to enhance experiences and take training to new levels; and gamification employing video-game technology to engage with users and make them come back for more. These sorts of initiatives and breakthroughs are leading to premium share prices and strong growth expectations in other sectors. Niche and imaginative for-profit approaches to education should be little different.The best approach is to break down for-profit education into key parts: schools and colleges; e-learning and professional/trade certification; textbooks, digitisation, distance learning and virtual attendance; and student accommodation and facilities management. This in turn gives a better idea of how various education and training trends are likely to translate into growth for investors.

A world of increasing regulation, for example, means whole industries have to put their staff through courses to get certificates often annually under continuous professional development that confers a level of competence required to continue in their roles. Financial services in the UK are a good example. Some employees undertake more ambitious training up to, and including, masters degrees to augment skills or build specialisms a junior lawyer studying intellectual property and patent law in-depth, perhaps. Or there are staff who must have regular training to keep their skills up to date aircrew hours in flight simulators would be an example.

At the same time, there are individuals who pay to undertake study to enhance their career prospects at their own expense and in their own time. Global population growth and an expanding middle class are drivers of this trend. Competition for good jobs and careers is high and, for many, the investment required is a price worth paying. In countries such as the UK, a common piece of urban wisdom passed on is the importance of saving for a deposit to get on and stay on the housing ladder. In areas such as London, however, it's redundant for many younger first-time buyers who have been priced out of the market and for whom the prospect of owning a property seems to keep getting further away. For the ambitious, accelerating their careers and income can be attractive as a means of catching-up. Rather than putting down a deposit for bricks and mortar, some are choosing to invest to lay down the building blocks of better jobs. The words of 18th-century US politician Benjamin Franklin seem as relevant today as they doubtless were more than 200 years ago: "An investment in knowledge always pays the best interest".

Global demand

Look beyond the UK to regions such as the Far East and the demand for further education is higher than in developed markets. The global middle class, a grouping that represented barely 5% of the global population in 1950, could make up nearly two-thirds by 2030, says The Brookings Institution think-tank in Washington. In 2015 the middle class spent $35trn on goods and services, a figure expected to leap to $64trn by 2030. Only a fraction of that increased spending will be from today's advanced economies it's mostly coming from countries such as India, China, Vietnam, Indonesia and Brazil. Education is likely to be a big beneficiary of the increased private-spending power and is likely to be further boosted in some countries by government support.

These factors together are making for a particularly fast-growing learning sector. But it goes both ways other countries with ageing, rather than younger, populations still need to push education. Getting older in a demographically older population may mean working beyond typical retirement age. That will require more ongoing development training and refreshing skills to switch to more suitable employment.

And, once in retirement, a number of people return to education to pursue personal interests. This is an important distinction to note because, unlike career development and corporate training, it plays into the theme of millennial aspiration. There is undoubtedly a shift that favours personal experiences and a more balanced lifestyle. Education is one route to fulfilling this it's less about degrees and more about bite-sized courses in skills such as painting or music as well as life-coaching and mentoring.

More importantly, perhaps, those who can learn from and understand how millennials respond to this type of training can design the kinds of corporate courses that will engage and prove popular with them millennials are growing into a dominant force socially and in the workforce.

Digitising education

There are many elements to education, but the most profitable hunting ground for investors is likely to be in innovation and the disruption of traditional approaches. Among the areas where this is occurring is digitising the delivery of courses and the further development of qualifications that can be achieved online without physically attending a bricks-and-mortar institution. This significantly opens up education to many more people anywhere in the world as the physical limits of capacity are removed. And, once the initial investment in developing the course, online portal and content has been made, each new pupil becomes extremely profitable over multiple course cycles even with syllabus updates and revisions. Not everyone can access colleges due to time and mobility constraints or personal commitments, and this should underpin demand for online distance learning, which is already showing good growth. Babson Survey Research Group, which has analysed trends in the US, reports consistently rising uptake of online courses for well over a decade. And the US Department of Education reports that 15.7% of all students in 2017 were enrolled exclusively on an online course, up 4% compared with 2016. A further 6.4% were studying online as well as taking other courses.

Major textbook publishers such as Pearson and McGraw-Hill have been going digital and reducing physical printing. What were once simply books are becoming interactive study aids, or even developing into standalone course modules. Accelerating digitisation goes hand in hand with online education offerings, although digital books also have wide application with students in traditional colleges.

E-learning goes mobile

Many of the approaches being adopted at colleges and other institutions to engage with students remotely in a compelling way are being picked up by e-learning developers. This is not unique to the corporate world (there are many subjects that aren't work-based at all), but e-learning has been especially fast in establishing itself as a routine part of life for workers as employers seek to boost skills or put in place a programme of short courses that help meet legal or regulatory requirements. This can mean anything from setting out health-and-safety rules, defining what discrimination is, or knowing when a customer should be suspected of an offence such as money laundering.

E-learning has already established itself as a multi-billion dollar global industry set to grow at the best part of 10% a year to 2025, according to researchers at Global Market Insights. Unsurprisingly, therefore, e-learning has attracted major players from software, consultancy and cloud computing, including Microsoft, Oracle, Citrix and Cisco Systems. Much of the training is undertaken on desktop computers, but there is a strong drive to make it as flexible and accessible as possible. The mobile phone is increasingly seen as the platform of choice for short courses and training. While e-learning can still seem novel and unfamiliar to employers, its expansion and the use of technology used in broader education is making people more familiar with it, and happier to use it.

Making training fun

Providers of training recognise, however, that it must be engaging and compelling because, for many, sitting down and completing online courses can come to be regarded as a distraction and a chore. Techniques are being borrowed from the world of gaming, for example, to help with this.

Work in these areas loosely falls under the umbrella of an aspect of the training industry referred to as education technology, or EdTech for short. Getting people to engage with learning is critical. At the global level, more than 380 million children complete primary education unable to read or carry out basic maths, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco). Anything that motivates them to want to learn and practise is no bad thing. For workers, meantime, who think they are familiar with e-learning, there's much still to come. Forget the clunky PC-based slides with the ten-question quiz. Get ready for enhanced digital whiteboards; machine learning and artificial intelligence developments that assess whether an employee really understands and shift the training dynamically; virtual reality to make training as realistic and practical as possible; and adaptive learning in which computers monitor where employees' skills are weak and direct individual programmes of learning until they're satisfied that gaps have been filled.

Physical institutions won't disappear

Of course, despite all these advances there will still be universities, colleges and many other types of learning institution. Investors will be drawn to the advanced developments, but there are still more down-to-earth ways to profit from education. An important one is real estate specifically, student accommodation. Good centres of academic excellence want to attract well-funded and competent students from all over the world. Modern, secure accommodation can be an important consideration. Building in certain locations allows property developers to demonstrate a required commitment to social provision. For investors, the rental streams, particularly from financially-backed overseas students with few alternative living options, can be reliable. This increases by seeking out the most committed students who are less likely to drop out masters or PhD students, for example.

So there are clearly many options for investors in the broad world of education. Below we look at some stocks that give exposure to many of these themes.

Four plays on the education sector

UK-listed Pearson (LSE: PSON) has been trying to grow market share by digitising its academic materials and textbooks. It is also active across education more broadly, with e-learning, professional certifications and virtual schools. Adjusting to the changing nature of education has been a drawn-out process and there have been disappointments for investors. However, there are signs that a revival is finally gaining traction while recent half-year sales were up just 2%, profits rose 35% to £144m, and the market responded positively. Pearson has still got progress to make and critics to disprove, but this could be a good opportunity to buy into a long-awaited turnaround. The shares trade on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of 14, with a dividend yield of 2.35%.

An alternative in the textbook market is Chegg (NYSE: CHGG). Once simply a seller of textbooks, this US-based business has successfully transformed itself into a dynamic digital education-service company with its main operations being renting out textbooks to hard-up students and online tutoring and support. The share price has been hitting fresh highs earlier this year. It continues to grow and is becoming profitable. Expectations are upbeat, meaning the shares are highly valued, on a forecast p/e ratio of 60. But its domestic market still represents a huge opportunity in which competitors have frequently struggled to build effective business models and perhaps lack the more grassroots engagement with students that Chegg seems to have.

Although much smaller, K12 (NYSE: LRN) has attracted investors with its model of offering public and private online schooling with ground-breaking curricula and technology solutions. There is a proven market for this among those educators and parents who feel children are not reaching their potential in traditional settings. The shares trade on a p/e of 32.

Leading UK student accommodation provider Unite Group (LSE: UTG) has recently agreed a deal to buy around 24,000 student beds at mid to high-quality institutions, taking its total bed count to 73,000 in 173 properties in 27 UK locations. The company is now valued at nearly £3bn, with its net assets valued at around £2.7bn by analysts. Free cash flow is strong and the stock currently yields 3.2%. The dividend is expected to grow around 13% a year, taking the yield to over 4% by 2021.

Unfortunately, investing in EdTech is not so easy because many of the emerging companies tend to be owned privately and aren't listed on stockmarkets. It's a common problem with emerging tech. Some of these companies will eventually be listed. In the meantime, Pearson, Chegg and K12 are all firms that bring exposure to EdTech they're developing their own technology, investing in small ventures and collaborating with others, so investors can get into EdTech opportunities under the cover of established broader businesses.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Stephen Connolly is the managing director of consultancy Plain Money. He has worked in investment banking and asset management for over 30 years and writes on business and finance topics.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement today (3 March). What can we expect in the speech?

-

Invest in space: the final frontier for investors

Invest in space: the final frontier for investorsCover Story Matthew Partridge takes a look at how to invest in space, and explores the top stocks to buy to build exposure to this rapidly expanding sector.

-

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growth

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growthCover Story It’s time to invest in Brazil as the economic powerhouse looks set to profit from the two key trends of the next 20 years: the global energy transition and population growth, says James McKeigue.

-

5 of the world’s best stocks

5 of the world’s best stocksCover Story Here are five of the world’s best stocks according to Rupert Hargreaves. He believes all of these businesses have unique advantages that will help them grow.

-

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sector

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sectorCover Story Move over, Silicon Valley. Over the past two decades the UK has become one of the main global hubs for tech start-ups. Matthew Partridge explains why, and highlights the most promising investments.

-

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?Cover Story Gold has always been the most reliable form of money. Now collaboration between China and Russia could lead to a new gold-backed means of exchange – giving prices a big boost, says Dominic Frisby

-

How to invest in videogames – a Great British success story

How to invest in videogames – a Great British success storyCover Story The pandemic gave the videogame sector a big boost, and that strong growth will endure. Bruce Packard provides an overview of the global outlook and assesses the four key UK-listed gaming firms.

-

How to invest in smart factories as the “fourth industrial revolution” arrives

How to invest in smart factories as the “fourth industrial revolution” arrivesCover Story Exciting new technologies and trends are coming together to change the face of manufacturing. Matthew Partridge looks at the companies that will drive the fourth industrial revolution.

-

Why now is a good time to buy diamond miners

Why now is a good time to buy diamond minersCover Story Demand for the gems is set to outstrip supply, making it a good time to buy miners, says David J. Stevenson.