How to protect yourself from dividend disappointment

Vodafone just cut its dividend. And it’s not the only company on shaky ground. John Stepek explains what’s so great about dividends, and how to protect your portfolio from dividend cuts.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

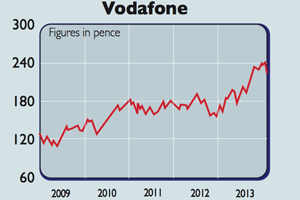

Earlier this week, Vodafone slashed its dividend.

It wasn't a huge surprise. A 9% yield screams "it's not going to be paid". Which is exactly what happened, as we discussed earlier in the week.

The thing is, Vodafone isn't the only UK-listed stock with a precarious payout. And they're not all quite as obviously at risk as Vodafone's was.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So as an investor, how can you protect yourself from these sorts of disappointments?

Why I like dividends

I like dividends. That's quite an old-fashioned view these days.

Clearly, not every company is at a stage where it can pay dividends. The presence or absence of a dividend payout does not mean a company is "good" or "bad". There are plenty of investment styles that entirely ignore dividends.

And I appreciate that there are all sorts of arguments about the tax efficiency of share buybacks (more so in the US) and arguments that any spare money should be re-invested in the business. A lot of these make sense. But they also, I feel, neglect certain aspects of real-world relationships.

Every publicly listed company has an agency problem. The people who run the company (the managers) are not the same people who own the company (the shareholders).

The management team is employed to make money for the shareholders. But managements also have their own self-interest, and sometimes what's good for the managers isn't good for the shareholders (or certain shareholders, anyway).

How do you think executive pay has climbed to its current ludicrous levels?

(And that's before we even point out that this principal-agent problem is made even worse by the fact that the ultimate owners of the company usually have another self-interested agent in the middle, in the form of a fund manager.)

So what I like about dividends is that they very visibly remind managements of who they're working for. The dividend payout can't be swept under the carpet or fudged with financial shenanigans. If it can't be paid, then managers face the embarrassment of having to cut or scrap it. They don't like that, as the reluctance to trim Vodafone's clearly overly-hopeful dividend demonstrates.

In short, a commitment to a dividend represents a rare incentive structure that works firmly in favour of the owner rather than the manager. It imposes a bit of discipline, which is no bad thing.

How to check on the safety of your dividend

So I have a lot of sympathy for investors who focus on dividends. The difficult thing is making sure that your payout is safe. And at the moment probably partly because of quantitative easing and the "pro-growth" environment it has created a lot of the stocks paying the chunkiest dividends are also not necessarily companies you'd be desperately keen to invest in otherwise.

For example, do you want to invest in high-yielding utilities, given the risks of re-nationalisation hanging over the sector? Do you want to invest in high-yielding retailers, given the misery on the high street that we're constantly warned about? Do you want to invest in high-yielding housebuilders, given both the risk of government support being withdrawn and the general slowdown in the market?

There are ways to check on how safe your dividend is. The obvious one is to look at dividend cover. This looks at how well dividend payouts are covered by earnings. You simply divide earnings per share by dividend per share.

A dividend cover of below one means that earnings don't cover the dividend payout, and suggest the dividend is on borrowed time. Vodafone, for example, had a dividend cover of around 0.9. Meanwhile, very few companies particularly the highest-yielding ones have dividend cover of more than two, which used to be deemed the benchmark for a "safe" payout.

Dividend cover is basic and it doesn't work uniformly. But it's not a bad starting point.

Also, like it or not, the yield itself is a massive clue. Right now, for example, utility group Centrica is yielding more than 12%. Is that going to be paid? I wouldn't bet on it.

Looking at dividend cover and yield won't, of course, protect you from unexpected events. There are risks with every industry. Any company involved in resource exploration can be hit by natural or operational disasters. Any company operating in the drugs business might be storing up a future liability in the form of side effects that only become apparent in the long term.

The irritatingly dull truth is that there's only one way to protect yourself from dividend cuts, and that's to diversify. You need to own a range of stocks across a range of industries. That way, if one cuts, your income isn't completely ruined.

I looked at some income-producing funds, focusing on the UK, that might be worth considering towards the end of last year. You can read that piece here.

However, I'd also suggest diversifying internationally. The FTSE 100 is a relatively high-yielding index but a lot of that yield is provided by a small number of companies, many of them with precarious dividend cover. We'll have more on that in MoneyWeek magazine later this month get your first six issues free here, if you don't already subscribe.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

Vodafone shares yield more than 6% – should you buy, or steer clear?

Vodafone shares yield more than 6% – should you buy, or steer clear?Analysis Vodafone grew revenue by 4% and profit by 11% last year, and offers investors a 6.4% dividend yield. So should you buy Vodafone shares? Rupert Hargreaves looks at the numbers.

-

Are your dividend payments at risk?

Tutorials Vodafone cut its dividend payment by 40% earlier this month. How can you avoid similar disappointments?

-

Vodafone takes fight to BT

News Telecoms giant Vodafone has vowed to take on BT in the broadband and television market.

-

Which companies will benefit most from Vodafone’s cash bonanza?

Which companies will benefit most from Vodafone’s cash bonanza?Features Vodafone shareholders are about to get a windfall. Ed Bowsher looks at how this will affect the markets, and how you could take advantage.

-

Company in the news: Vodafone

Company in the news: VodafoneTutorials If you own shares in Vodafone, you're in for a big pay-out. Phil Oakley explains how it will work, and what you should do next.

-

Company in the news: Vodafone

Features Vodafone shareholders are in for big windfall following the deal with Verizon. But once the money's paid out, are the shares worth keeping? Phil Oakley investigates.

-

Vodafone’s $130bn deal

News Mobile-phone giant Vodafone has sold its stake in Verizon - the biggest deal for a decade.