Goodwin heads for calmer waters

Profitability at British engineer Goodwin has slid in the past few years, but the outlook has greatly improved.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Goodwin (LSE: GDWN), a British engineering firm founded in 1883 that grew rapidly for most of this century, has had a tough time of it in recent years. But the outlook is improving.

Before the oil price crashed in 2014, 60% of the revenue from Goodwin's mechanical engineering division stemmed from oil and gas companies. The manufacture of giant valves used in pipelines, terminals, rigs and tankers is the main activity here.

When customers reduced investment, profitability slumped, but this year's annual report promises a prosperous future, and at the firm's annual general meeting earlier this month the board's confidence was palpable. And the positive outlook is not just based on the rising oil price.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Preparing for recovery

While fewer orders were flowing through the foundry, Goodwin took the opportunity to install bigger and more sophisticated plant capable of casting even larger products weighing up to 35 tonnes a size that relatively few foundries around the world can match. Goodwin completed the lengthy approval process required to supply the US Navy last year, and has secured the first of what the company believes will be many orders supplying its shipbuilding programme. It is also targeting the US civilian and military nuclear industries, which also require huge high-integrity castings for nuclear reprocessing and propulsion systems.

Goodwin has averaged a return on capital of 9% over the last three years, way below the long-term average, but it could have been worse had it not been for Goodwin's other key division, refractory engineering.

This group of companies mostly supplies minerals for making wax moulds used to cast jewellery. The mass production of relatively low-value silver, brass and gold jewellery is big business in the Far East, where the market is growing strongly and profit margins have been transformed since an erstwhile major competitor, Kerr, stopped selling jewellery-casting powder. Earnings from refractory engineering modestly eclipsed those of mechanical engineering in the year to April 2018.

Oil prices will boost sales

The third factor in Goodwin's likely resurgence is, of course, the higher oil price, which is strengthening the finances of oil and gas companies and should give them the confidence to invest again. Goodwin expects to be doing more oil-related business next year, too, lifting it above the 40% of revenue it currently provides. Thanks to the group's new revenue streams, however, the majority of revenue from mechanical engineering is unlikely to come from oil again. That is probably a good thing, given the rapid adoption of renewable energy.

Growing optimism is reflected in the share price, which has risen sharply since the company reported strong cash flows and a modest increase in profit for the year to April 2018. The share price values the firm at about 20 times adjusted profit on a debt- adjusted basis, but this may be one of those occasions where historic earnings multiples are not particularly revealing. If the company fulfils its promise, relatively low levels of profit in 2016, 2017 and 2018 will be footnotes in Goodwin's financial history.

The Goodwin AGM

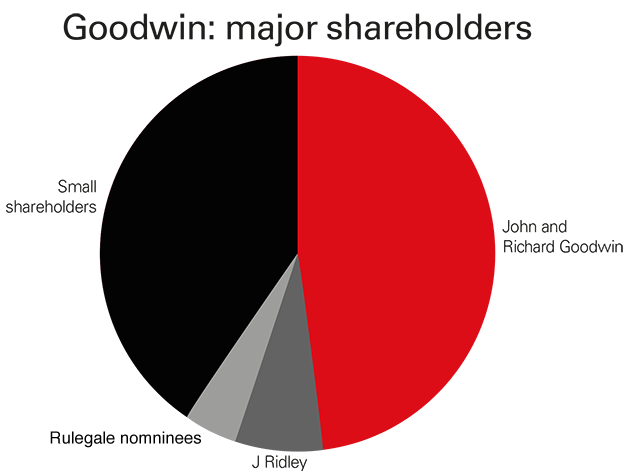

Goodwin is run by brothers Richard and John Goodwin, who own the largest portion of the shares. A restricted pool of shares prevents funds buying them in the quantities they require, and they might not want to in any case because the Goodwin family's shareholding gives it control of the company.

Lack of institutional interest means there are no broker forecasts, and few articles in the press, but it also means Goodwin is easily overlooked and may be undervalued. One way for investors to find out more about a company with a low profile is to attend its annual general meeting (AGM). You must be a shareholder to vote, but often firms will allow outsiders to attend and ask questions after the formal business is finished.

I attended Goodwin's AGM as a shareholder, partly to confirm my impression that it is a very well-managed business, and partly to decide whether I can trust the family to act in the interests of all shareholders.

The AGM confirmed my favourable assessment of the firm. Goodwin has earned an average return on capital of 18% over the last decade. It has patents and facilities that mean it can do work few other firms can, and the board says it only takes on high-margin work so profitability should recover.

My one reservation is a pay policy introduced in 2016 that will give each executive director shares worth up to 1% of the total value of the company in April 2019, depending on the performance of the share price.

This represents a transfer of ownership from shareholders to the board, four of them sons of Richard and John Goodwin. Although shareholders' stake will have increased in value by much more than the dilution they will experience if the award is triggered in full, the convoluted nature of the incentive plan has left me questioning the motives of the board for the first time. Its openness and attentiveness to shareholders at the AGM has mollified me somewhat, but before the board puts pay to the vote at next year's AGM I shall petition it to adopt a more transparent policy.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Richard Beddard founded an investment club before joining Interactive Investor as an editor at the height of the dotcom boom in 1999. in 2007 he started the Share Sleuth column for Money Observer magazine, which tracks a virtual portfolio of shares selected for the long-term by Richard. His career highlights include interviewing Nobel prize winners, private investors and many, many company executives.

Richard is freelance writer who invests in company shares and funds through his self-invested personal pension. He has worked as a teacher and in educational publishing, and is a governor at University Technology College, Cambridge. He supports the Livingstone Tanzania Trust, a charity supporting education and enterprise in Tanzania.

Richard studied International History and Politics at the University of Leeds, winning the Drummond-Wolff Prize for "distinguished work in the field of international relations".

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King