“Peak Water”: how to invest in a world that’s drying up

There’s water everywhere, but if there is to be a drop to drink in the future, big changes will be needed. Investors can help keep the taps running, says Stuart Watkins.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There's water everywhere, but if there is to be a drop to drink in the future, big changes will be needed. Investors can help keep the taps running, says Stuart Watkins.

Early this year Cape Town's four million residents were keeping an eye on dam water levels with an obsessiveness usually reserved for Twitter, as local academic Hedley Twidle puts it in the Financial Times. Daily water consumption was restricted to just 50 litres per person per day about a third of average UK usage. "Day Zero" the date the city's rapidly evaporating reservoirs were expected to reach critical levels was months away.

At that point, the taps were to be shut off and about a million households would have to queue at water-collection points for daily rations of just 25 litres. Following an unprecedented drought, Cape Town was on course to become the world's first city to run out of water.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Reaching "Peak Water"

This was just the latest episode in a growing global water-shortage crisis that many predict will get worse with climate change, and which could lead to major public-health disasters, social and political unrest, and even wars. Cape Town, like many places in the world, has reached "Peak Water", as water scientist Peter Gleick told National Geographic. "What's happening in Cape Town could happen anywhere."

As we all know from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem, finding water and a drop to drink are different propositions. Three-quarters of the Earth's surface is covered with the stuff, but only about 3% is fresh.

And while shortages of potable water have been a recurrent concern for decades, the problem is getting worse for several reasons: worsening pollution as industrialising societies produce vast quantities of pesticides, fertilisers and heavy metals; increasing population and urbanisation, which places new demands on supply; and climate change. The latter tends to make drier areas drier, causing droughts, and wetter ones wetter still, causing flooding. Other global changes, such as deforestation, only add to the challenges.

Demand is on the rise

We live on an increasingly thirsty planet. The world's population has grown to more than 7.5 billion, yet more than one billion lack access to water. Of the world's 500 largest cities, reports the BBC, one in four are estimated to be in a situation of "water stress" when demand for water exceeds supply over a period of time. According to projections endorsed by the United Nations (UN), global demand for fresh water could exceed supply by 40% in 2030. The water we draw from our taps or use to flush our loos is only the most visible part of a much bigger iceberg of demand for "invisible" or "virtual" water.

The scale is captured nicely in a line by Fiona Harvey in the Guardian: how do you get 130 litres of water into a single cup? Just fill it with a cup of coffee. Growing coffee beans is a thirsty business, she says, as is growing cotton 10,000 litres goes into a pair of jeans, 2,500 into the average T-shirt. Even bottles of water themselves are highly water-intensive products.

Overall global demand for water has been increasing at a rate of about 1% a year over the past decades and will continue to grow for the foreseeable future, according to a UN report. Industrial and domestic demand is set to rise faster than agricultural demand, although agriculture will remain the largest overall user: it uses about 70% of fresh water across the globe; 20% goes to industry, 10% to households.

And the vast majority of the growth in demand will occur in countries with developing economies. Unless comprehensive action is taken to reduce the stress on rivers, lakes, aquifers, wetlands and reservoirs, the trend points to more than five billion people suffering water shortages by 2050, the report warns.

Are we heading for water wars?

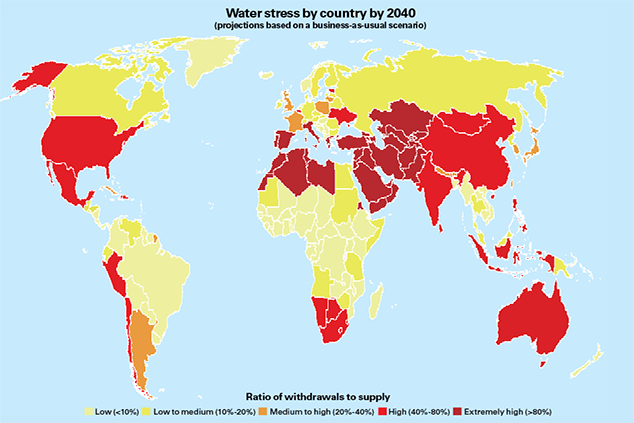

The global distribution of water supplies and geopolitics can exacerbate the demand-supply imbalance. The Earth's water resources are unevenly distributed (see map below), and getting it from where it is to where it's needed is expensive and laborious, particularly if it has to move across borders. As the world's population grows and becomes ever more concentrated in cities, finding enough water both to grow food and keep the taps running can be a great challenge, and is responsible for the over-exploitation of many rivers and groundwater aquifers worldwide.

But if you're situated downstream from a geopolitical rival on that overexploited river, your problems are only just beginning. As John Dizard puts it in the FT, if it is bad for a country to lack the foreign exchange necessary to meet operating expenses or debt payments, then it is much worse for it to lack water. Much of the Middle East faces just such a prospect. Turkey's recent damming of the Tigris river, for example, and its filling of a reservoir, left downstream Iraq to face up to the fact that "water poverty more than offsets oil wealth".

Turkey, where the Tigris and Euphrates originate, has much more latitude than is typical in the West in how it releases water to its neighbours. Water shortages pose an immediate existential threat to Turkey's regional rival Iran, where drought afflicts 97% of the country. Iran's most serious recent protests were not about internal politics or relations with America, but about water.

Since 2000, 357 disputes over water have occurred worldwide, according to the Pacific Institute, a US think tank. Of those, 93 took place in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by 90 in the Middle East and 60 in south Asia, corresponding to areas with high population growth that are prone to drought damage. Scott Moore of Foreign Affairs reckons the chances of these disputes turning into wars is small, but they can destabilise local and national politics, and lead to large-scale population movements and other challenges for foreign and security policy.

Tackling the problem

All this may seem a long way from our drizzly shores, but we don't get off scot-free either. London ranks among the 11 cities after Cape Town most likely to run out of water, reports the BBC. With an average annual rainfall of about 600mm (less than the Paris average and only about half that of New York), London is likely to face supply problems by 2025 and "serious shortages" by 2040.

Should we panic? Well, you needn't as long as someone else is. As Twidle reports in the FT, she was never too concerned about the panic in Cape Town as she knew someone in the water-policy world who was adamant that Day Zero would never actually happen. It was a social and political fiction, he said. Yet it was also a necessary fiction in other words, the dangers are real, and public concern itself entered the equation as a factor in whether or not, or with what sense of urgency, something was actually done about them.

Day Zero has now been pushed forward to 2019, and remarkably that was largely down to the authorities urging the public to save water. A good ticking off and an education campaign may be all it takes to save the world from disaster. When it comes to thinking about serious environmental issues, it's easy to veer off in one of two directions, as Twidle says.

Either you think we're heading for "a Mad Max dystopia, a world of water barons and social meltdown", or there will be some "miraculous fix of hydro-modernist geo-engineering, a utopian cure-all". The reality is likely to be more messy an overlapping series of small changes and accommodations, a mixture of "slowly retrofitting existing systems and gradually modifying what once seemed natural behaviours".

Indeed, newspapers may be awash with alarming stories warning of a water crisis, says Moore in Foreign Affairs, but "a funny thing happens between the headlines: surprisingly little". Cape Town provides a prime example. Still, that doesn't mean the water crisis is not real. It's just that the problem is relatively simply if not easily solved. It just takes enough money and willpower.

Water pricing may seem to be the obvious way forward solving the water crisis will require behavioural change, as Moore says, "something high prices are uniquely good at motivating". Yet political and ethical issues make this hard to achieve in reality. The UN has proclaimed access to water a human right, which makes it politically difficult to then charge for it, especially as those worst affected will struggle to pay.

How technology will help

That leaves technical solutions. These should allow most places to avoid a true water crisis, says Moore. Areas facing water scarcity can do much to improve their security of supply simply by using the water they have more efficiently, for example. In most cities rain is channelled into sewers, but storm water can be collected and recycled, as can waste water, which cities such as Singapore treat and use to meet some 40% of total water needs. In agriculture, water conservation technologies can help, including "drip irrigation", which gives crops exactly the right amount of water to maximise yield.

Desalination technologies which are energy-intensive but are rapidly improving in efficiency could protect coastal cities such as Cape Town from drought. Newer technologies, such as small-scale solar-powered desalination, or "off-grid" systems that harvest water from the air, might help too. Veragon, a London-based company, says it has a commercially viable solution for condensing water from air that is being sold to the Italian military, Nato and the UN World Food Programme, reports the FT, as well as to commercial distributors.

Israel shows the way

Israel could be a model for the rest of the world, as Ruth Schuster points out in Haaretz, an Israeli newspaper. According to Seth Siegel, author of the best-selling book Let There Be Water, 60% of Israel's land is desert and the rest is arid. Rainfall has fallen to half its 1948 average, apparently due to climate change, and since 1948 Israel's population has grown tenfold. Yet rather than submit to its fate, Israel has "largely separated its water consumption from Mother Nature" by implementing a holistic, centralised water-management system.

It has drilled deep wells, embarked on a massive desalination programme, reused treated sewage for farming, found and fixed leaks early, engineered crops to thrive in onerous conditions, discouraged gardening, made efficient toilets mandatory, priced water to discourage waste and introduced drip irrigation. The world doesn't need to figure out how to solve its water problem, says Siegel: Israel has done the work already. But it's expensive work. The real question for the world's water sector remains, says Moore, not how much blue, but rather "how much green flows into it".

A staggering amount of green

A staggering amount will be needed, says the FT. Annual investments of $449bn in water infrastructure are required to meet the targets laid out in the UN's Sustainable Development Goals, according to Global Water Intelligence. Others say even more spending is needed, with estimates ranging from $6.7trn by 2030 to $22.6trn by 2050. But there is a growing awareness in industry that water stewardship matters, Kate Brauman, lead scientist at the University of Minnesota's Global Water Initiative, told MoneyWeek.

She is particularly impressed with work done by the sustainability organisation Ceres, which collaborates with institutional investors to address water issues. As Mindy Lubber points out on Ceres's blog, water scarcity issues can have some unexpected consequences for investors. For instance, at least 50% of the stocks listed in each of the four major US stock indices are in industries with medium to high water risks, according to its own research. The heatwaves and droughts across Europe and Asia have sent wheat futures to three-year highs.

Four nuclear power plants in France were temporarily shut down this summer when they were unable to withdraw cooling water from unusually warm rivers. And according to a report that hit the headlines last week, extreme heatwaves and droughts, exacerbated by climate change, will increasingly damage the global barley crop, which will lead to beer shortages. If that doesn't concentrate minds, nothing will.

The water stocks to buy now

The cheapest and simplest way to invest in companies tackling global water scarcity is through exchange-traded funds (ETFs), though many of these have large parts of their portfolios allocated to conventional water utilities. One that concentrates more on technology aimed at addressing water shortages, with an emphasis on small and mid-cap companies, is the PowerShares Water Resources Portfolio (Nasdaq: PHO).

It tracks Nasdaq OMX US Water, an index of companies that focus on the provision of potable water and its treatment. The ETF has made a total return of just over 16% in three years and has a total expense ratio of 0.62%. It's not exactly an exciting holding, as James Brumley on InvestorPlace.com says, but it is a steady performer that should pay off in the long run. The case for buying it "holds water". UK-listed alternatives include the iShares Global Water(LSE: IH20) and Lyxor World Water (LSE: WATL) ETFs, although these have greater exposure to water utilities.

Perhaps the best individual stock to play the theme, and a top-ten holding in all three of those ETFs, is Xylem (NYSE: XYL). It operates in water infrastructure and applied commercial and industrial water technologies. But it is the company's smallest division, in measurement and control technologies, that is "arguably its most exciting", says Lee Samaha on Motley Fool.

When water is scarce, it's crucial that public utilities and industrial companies be able to monitor water usage to ensure they're using it efficiently. The firm's $1.7bn acquisition of Sensus (a global leader in smart meters, network technology, and data analytics) in 2016 helped boost Xylem's growth rate. "As long as public utilities (47% of Xylem's revenue) in developed and emerging economies are spending on water and wastewater projects, then Xylem has a bright long-term future."

One of US investment magazine Barron's favourite plays is Tetra Tech (Nasdaq: TTEK). It provides consulting, engineering, and programme-management services to big water-infrastructure projects. Tetra Tech earns roughly 40% of its revenues from US federal, state, and local governments, and 30% overseas. Its order backlog from international developments has grown 34% year over year to a record $2.5bn. Recent deals, such as its acquisition of Eco Logical Australia, have expanded its exposure to environmental and water services in the Asian-Pacific region.

Mueller Water Products (NYSE: MWA) manufactures a broad range of water infrastructure and flow-control products for use in water-distribution networks and water and wastewater treatment facilities, including engineered valves, hydrants and pipe fittings. It is a financially robust, dividend-paying company with a history of strong performance, says Arjun Bhatia on Simply Wall St News. Earnings are up 86% over the past year. The company has plenty of cash on its balance sheet and a history of regularly increasing dividend payments over the past decade.

Finally, consider French infrastructure giant Veolia (Paris: VIE). It is generally regarded as a plodding rubbish-disposal group, but its water treatment divisionis also a global leader in seawater desalination technology, notes Garry White, an analyst at Charles Stanley. That makes up a small but promising part of its overall business: Veolia has built more than 1,950 desalination systems in 85 countries over the last four decades.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Stuart graduated from the University of Leeds with an honours degree in biochemistry and molecular biology, and from Bath Spa University College with a postgraduate diploma in creative writing.

He started his career in journalism working on newspapers and magazines for the medical profession before joining MoneyWeek shortly after its first issue appeared in November 2000. He has worked for the magazine ever since, and is now the comment editor.

He has long had an interest in political economy and philosophy and writes occasional think pieces on this theme for the magazine, as well as a weekly round up of the best blogs in finance.

His work has appeared in The Lancet and The Idler and in numerous other small-press and online publications.

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026

-

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continue

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continueIt was another difficult year for fund inflows but there are signs that investors are returning to the financial markets

-

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debt

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debtCover Story Rising interest rates and soaring inflation will leave many governments with unsustainable debts. Get set for a wave of sovereign defaults, says Jonathan Compton.

-

Why Australia’s luck is set to run out

Why Australia’s luck is set to run outCover Story A low-quality election campaign in Australia has produced a government with no clear strategy. That’s bad news in an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment, says Philip Pilkington

-

Why new technology is the future of the construction industry

Why new technology is the future of the construction industryCover Story The construction industry faces many challenges. New technologies from augmented reality and digitisation to exoskeletons and robotics can help solve them. Matthew Partridge reports.

-

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?Cover Story Universal basic income, the idea that everyone should be paid a liveable income by the state, no strings attached, was once for the birds. Now it seems it’s on the brink of being rolled out, says Stuart Watkins.

-

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolio

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolioCover Story Unlike in 2008, widespread money printing and government spending are pushing up prices. Central banks can’t raise interest rates because the world can’t afford it, says John Stepek. Here’s what happens next

-

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?Cover Story Joe Biden’s latest stimulus package threatens to fuel inflation around the globe. What should investors do?

-

What the race for the White House means for your money

What the race for the White House means for your moneyCover Story American voters are about to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will take the oath of office on 20 January. Matthew Partridge explains how various election scenarios could affect your portfolio.

-

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?Cover Story Politicians of all stripes increasingly agree with Karl Marx on one point – that monopolies are an inevitable consequence of free-market capitalism, and must be broken up. Are they right? Stuart Watkins isn’t so sure.