Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

As new technologies become ever more sophisticated, we're generating mind-boggling volumes of data. The firms capable of analysing it are sitting on a gold mine, says Ben Judge.

Ever since tally sticks were invented, humans have used data to keep track of the world around them. Writing allowed us to store and retrieve data. The abacus enabled us to make complex calculations. Then in the 20th century the world went digital, and data came in the form of machine-readable ones and zeroes. But it was with the arrival of the internet and widespread wireless communication that our capacity for generating, storing and analysing data went through the roof.

The sheer volume of data we generate is mind-boggling. An oft-quoted statistic from computer-giant IBM is that we generate 2.5 billion gigabytes of data every single day, and that 90% of the data ever created has been made in the last two years. But that statistic comes from 2012. In the subsequent five years, the number of monthly active Facebook users has almost doubled to around two billion, and the number of internet users in China has doubled to one billion, according to statistics website Statista, the majority of them using smartphones.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This data explosion is "giving rise to a new economy", says The Economist. It is "unlike any previous resource"; it "changes the rules for markets and it demands new approaches from regulators Flows of data have created new infrastructure, new businesses, new monopolies, new politics and crucially new economics." The new economy need not be market driven, either. Some observers believe that "big data" as the sector has become known could even revive the planned economy. "Big data will make the market smarter and make it possible to plan and predict market forces so as to allow us to finally achieve a planned economy," argues Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, China's biggest e-commerce conglomerate (although as someone who operates at the indulgence of a Communist government within a heavily centralised, planned economy, Ma may have ulterior motives for presenting big data in this way).

In any case, a whole new industry encompassing data collection, storage, analysis and sale has sprung up in line with the escalating quantities of data. The UK now employs more than 30,000 people in specialist roles, according to the government a number that is expected to more than triple in the next five years. In fact, Britain is the largest data-centre market in Europe, with more than 26% of the region's capacity. The industry is expected to generate £241bn in economic value by 2020.

There is no sign of this growth levelling off. Not a single aspect of our lives remains that has not been, or will not in the very near future, be digitised in some way. More than half of the world's households have access to the internet, according to the International Telecommunication Union, and 70% of the world's youth is online. Moreover, people are increasingly using the internet via mobile devices there are 2.3 billion smartphone users in the world, according to Statista which means that their "connected" devices accompany them pretty much wherever they go.

If you use a smartphone, you're generating data. You might not think that where you go and what you do is particularly interesting to anyone else. But add up all the data generated by people going about their everyday lives, and a surprising amount of information can be inferred. We now use our phones as "remote controls for life", says Liz Brandt of the consultancy Ctrl-Shift. The amount of computing power we now routinely carry around is unprecedented. In the West, technology giants including Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Google collect and store vast amounts of data on their customers. In China, Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu do exactly the same thing.

The "internet of things" (which covers both smartphones and more mundane household devices that happen to be connected to the internet) is constantly sucking up data and relaying it to huge data farms for analysis. And these connected devices are proliferating rapidly. There are 27 billion internet-connected devices globally, says IHS Markit. By 2030, Markit expects that to be at least 125 billion, as consumers buy ever more smart home (such as internet-enabled thermostats, say), and wearable devices, such as smart watches.

Smarter cities and hospitals

The public sector is getting in on the act, too. "Smart cities" will in theory use data from sensors to improve everything from traffic flow and pollution to public safety and energy usage. Over the next 20 years, cities around the world are expected to spend $41trn on smart-city initiatives, says the SmartAmerica Challenge, a White House programme set up to harness new technology for public benefit. In a typically American solution, for example, the city of Boston is just one of several that has been using a network of sensors to detect gunshots since 2008, says Aneri Pattani on CNBC.The system produced and marketed by listed company ShotSpotter alerts the police within seconds with details of where the shots were fired. In the UK, Transport for London used data from passengers' smartphones to map out how they navigated the underground rail system. They hope the data will help them to find ways to reduce overcrowding. And in a pilot study earlier this year, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) tracked the commuting patterns of thousands of people via their phones. The hope is that the ONS will be able to use this type of analysis, coupled with scraping its already huge public databases for information, to supplement, improve on, or even replace census data.

The NHS, meanwhile, hopes to use the huge volume of data it collects to improve patient care. NHS Scotland, which started digitising patient records in 2011, has trialled the use of data analytics to improve diabetes care. If the same process were used in NHS England, says Capgemini, it could save £37m a year in reduced amputations. A controversial tie up between London's Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust and Google's DeepMind artificial intelligence unit aims to develop an app that can detect early signs of kidney failure and alert medical staff. Acute kidney illness is involved in as many as 40,000 deaths in England each years, costing the NHS more than £1bn, says the Royal Free. However, the trial fell foul of data-protection rules. The Information Commissioner, the UK's data regulator, acknowledged that "there's no doubting the huge potential that creative use of data could have on patient care and clinical improvements, but the price of innovation does not need to be the erosion of fundamental privacy rights".

Who is hanging on to your data?

The case highlights the concerns many people have that unfettered access to personal data by commercial companies or public-sector bodies is not necessarily a good thing. And indeed, the regulatory regime in Europe is changing to address some of those fears. On 25 May 2018, the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force. GDPR will tighten up the rules on collection and processing of personal data, and will apply to any company that stores or processes the data of EU citizens including US firms. US companies do appear to be taking it seriously 92% of those surveyed by PwC considered it a "top priority on their data-privacy and security agenda", with 68% of them saying they will invest between $1m and $10m; 9% expect to spend over $10m.

In China, the government has no such qualms about personal privacy. "Ten years ago, the internet revolution seemed to present a threat to authoritarian rulers. Today, Big Data plays into their hands," says Sebastian Heilmann in the Financial Times. The government is hoping to use information on currency movements, credit flows and investments to fine tune the economy and "allow for smarter resource allocation than market-based price echanisms" (echoing Jack Ma's comments above). More sinisterly, by 2020 all citizens will be enrolled in its "Social Credit System", whether they like it or not. Everything they do will be monitored what they buy, who they talk to, even if they obey traffic rules and used to create a "Citizen Score" that determines trustworthiness and loyalty to the regime, and is publicly ranked alongside others' scores. Tencent recently released an app that shows speeches made by Chinese premier Xi Jinping, and rates the enthusiasm with which users applaud. It's "a dream come true for authoritarian regimes focused on maintaining order", says Heilmann.

Big data and the City

At the other extreme, financial professionals are using big data to make more profitable investment decisions. "The exponential growth in data is fuelling our investment decisions and research agenda," says Dennis Walsh of Goldman Sachs' Quantitative Investment Strategies team. The growth of "non-traditional data sources such as internet web traffic, patent filings and satellite imagery" gives Goldman an "informational advantage", adds his colleague Osman Ali. Hedge funds are increasingly turning to "non-traditional" forms of data 46% of those featured in consultancy EY's 2017 Global Hedge Fund and Investor Survey now use it, with 18% of those investing heavily in big data. Of those who are not currently using non-traditional data, 21% expect to do so. The most popular source is social media, with 27% of respondents using or planning to use it; 27% plan to use private-company data; and 25% credit-card data.

As a result, companies have sprung up to harvest this data and sell it on. "There's a gold rush in data mining," Sandy Rattray, chief investment officer of Man Group, tells the FT. "Most people who went off to prospect for gold came back penniless, but that doesn't mean there wasn't any gold." The website AlternativeData.org, backed by YipitData, one of the biggest data providers, suggests there are nearly 200 firms now providing this sort of data.

The data treasuries

All of this data might seem ephemeral but it has to be stored somewhere. Firms are now spending record sums on building data centres. "Investment in data-centre real estate has reached fever pitch," says real-estate investment firm CBRE. In the first half of 2017, a total of $18.2bn was invested, more than double that of 2016 as a whole. Amazon, Microsoft and Google are the biggest players in the sector, and yet the world's biggest data centres are not in the US. The biggest is the Range International Information Hub in Langfang, northern China, covering more than six million square feet. It is run jointly by IBM and Beijing-based Range Technology Development Company. By comparison, Switch's "Super NAP" data centre in Las Vegas, the biggest in the US, covers just over two million square feet.

But all this data is worthless without the ability to analyse it. Whereas in the early days of data collection, data was logically structured in relatively easy-to-read databases, it is now unstructured (which is where the notion of "big data" comes from), and has to be analysed by artificial intelligence and machine learning processes. The provision of software and systems that can help make sense of this data is a major growth industry. Below, we look at firms making strides in this area.

Five investments to buy now

As with any hot sector, stocks in the big-data niche tend to be expensive. However, there is little by way of funds that invest specifically in the area. The one exchange-traded fund (ETF) that did exist, PureFunds ISE Big Data ETF, closed earlier this year, partly because of a lack of interest from investors its exposure to the sector wasn't considered "pure" enough. That said, in an era where ETF launches can often signal overheating in a sector, this is perhaps a good sign.

On the data storage and infrastructure side, the biggest players are the tech giants: Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN), Microsoft (Nasdaq: MSFT) and Google's parent Alphabet (Nasdaq: GOOGL) in the US, and Baidu (Nasdaq: BIDU), Tencent (HK: 0700) and Alibaba (NYSE: BABA) in China. You have exposure to pretty much all of these if you own the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (LSE: SMT). The trust which has done spectacularly well in recent years is currently part of the MoneyWeek investment trust portfolio, but we're eyeing it warily given the increasing scrutiny of the big tech stocks (we'll update on the portfolio before the end of the year).

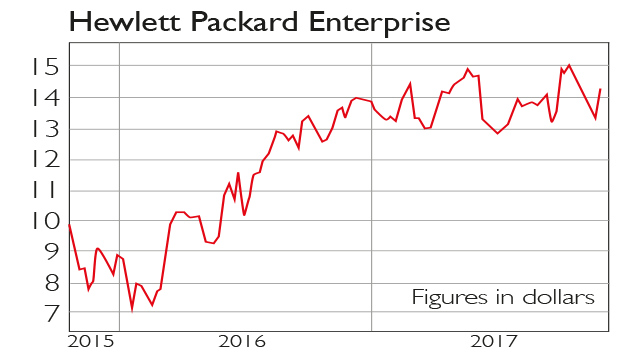

On the hardware side, Cisco (Nasdaq: CSCO) is one of the world's biggest network hardware firms. It trades on a price/earnings (p/e) multiple of 15, and yields around 3%. In 2016, hardware manufacturer Hewlett Packard split into two: HP Inc continued to make computers and printers, while Hewlett Packard Enterprise (NYSE: HPE) focused on data-centre hardware and big-data analytics it trades on a p/e of 11 and yields 2%.

San Francisco-based Splunk (Nasdaq: SPLK) makes software that can analyse machine-generated big data. It takes the unstructured data generated by sensors and the like and turns it into something that firms can work with. Splunk's shares leapt this month, after third-quarter earnings beat expectations. It aims to double annual sales to $2bn by 2020.

Much of the processing of big data sets is done via the Apache Foundation's open source Hadoop software. IBM provides analytics software on Hadoop, and has partnered with Hortonworks (Nasdaq: HDP) to do so. The latter's share price is about 25% below its 2014 listing price, but has rallied rapidly this year.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King