India: the "almost-perfect" emerging-market investment story

India is almost the perfect emerging-market investment story. But don’t just pile blindly into Indian stocks, says Merryn Somerset Webb. There are much better ways to invest.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Want to ride on a Shinkansen? Of course you do. Everyone wants to ride on a bullet train. But unless you get to Japan at some point in the next few years, you might find that most of India rides on one before you do.

This week, Japan's prime minister Shinzo Abe headed to India to lay the first stone in a Japanese-financed $17bn bullet train project set to cover the 310 miles between Mumbai and the industrial city of Ahmedabad. This is exciting stuff. That's partly because bullet trains are amazing in themselves this one will cut the journey time from eight hours to under three.

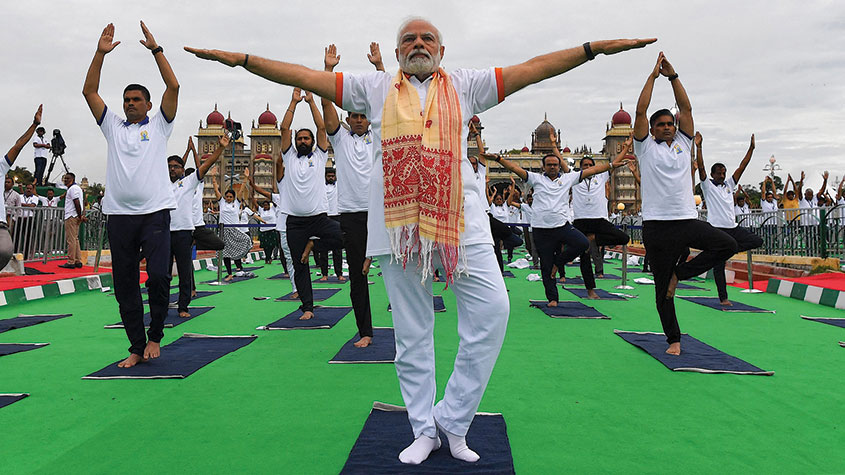

It is partly because the Japanese have offered a fabulous deal on the finance and are signing various other investment deals along the way. But the really interesting thing is the speed of delivery of the project: India's prime minister Narendra Modi first decided to bring high-speed trains to India only two years ago.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Two years from thought to first stone laying is quite something for a major infrastructure project. For comparison, you might note that the new tram system in Edinburgh, where I live, was first proposed in 2001. It was completed in 2014. It covers 8.7 miles. Very slowly.

"My good friend prime minister Narendra Modi is a far-sighted leader", said Abe this week. Such compliments are a rare thing in politics. Perhaps Modi is far-sighted; it is certainly true that he is prepared to make decisions that bring nasty short term pain and hit growth with a view to long-term gain.

Late last year, he brought chaos to India's economy with the abolition of two large-denomination banknotes in an attempt to move towards a clean and taxpaying digital economy. The consumer economy stalled; there were huge lines at the banks; and everyone working in the black economy found themselves having to choose between coming clean or losing their savings. But Modi held firm.

He has done the same with this summer's implementation of a national goods and services tax. It has subdued growth across the board but should pay huge dividends as it slashes corruption, simplifies the tax system and boosts revenues.

This is all good. But it is just the icing on the cake of an almost perfect emerging-markets story. India has fabulous demographics (two-thirds of the population are of working age); a booming middle class keen on consumption; a fast-shrinking current account deficit (under 1& of GDP); a government committed to housing and infrastructure spending (there is a kind-sounding "Housing for All" scheme on the go); and a low fiscal deficit (down to 3.5%).

It also has a high level of foreign-exchange reserves (about $400bn) and inflation looks to be properly under control (down to more like 2% nowadays, compared to about 6% a year ago).

Some of these things could reverse if the oil price rises again the current-account deficit would rise again, for example. But for now, while there are some worries around employment and credit growth, the macro environment looks mightily impressive (imagine how thrilled we would all be if the UK's numbers looked anything as good).

India's stockmarket looks good, too. It is one of the few emerging markets with real depth and breadth: you can get exposure to pretty much any part of the economy you want via a listed company (not all are top quality, of course, but that's not exactly an emerging-market specific problem).

Finally, it is worth noting that India's stockmarket is supported by local investors rather than just by the fickle international investors who cause so much volatility in emerging markets (they were the ones who sold so energetically when Donald Trump was elected and when the geopolitics around North Korea started to heat up last month, for example).

You will all be wanting to rush in. Don't. I am not exactly the first to point out the merits of investing in India. They are obvious to everyone hence the 23% rise in the market so far this year and the stunningly high valuations of the type of companies international investors fancy.

The average valuation of companies that make up India's benchmark NSE Nifty 50 Index is about 18 times earnings. This may come down fast as the growth-damping effects of demonetisation and tax harmonisation disappear (earnings relative to GDP are close to historical lows at the moment, and these things do tend to revert to the mean). But 18 times is still far from cheap for an emerging market.

That said, when I was asked at the FT Weekend Festival a few weeks ago if you should have exposure to India, I gave a firm "yes" in reply. You should own a starter stake and plan to buy more when the inevitable global correction comes.

You should do this via a fund. There is no planet on which someone sitting in front of a laptop in the UK Home Counties can possibly know enough about individual companies in India successfully to pick stocks (the same goes for China, by the way). If you try this and end up making money, it will have been a fluke.

So a fund it is. There are three India-focused investment trusts worth looking at in the UK, including the Aberdeen New India (LSE: ANII) and the JP Morgan Indian investment trust (LSE: JPII). But the one that looks most interesting to me at the moment is the India Capital Growth Fund (LSE: IGC). It isn't particularly cheap (it has an irritatingly high ongoing charge of 1.79%), but invests in high-quality mid- to small-cap stocks in India for the long term (most current holdings have been in the fund for three years or so). The fund has a good team on the ground, and trades on a 14% discount to net asset value, despite a sparkling record: the net asset value is up 200% over the past five years.

If India is a bit too spicy for your investment appetite, you might look at Nick Greenwood's CF Miton Worldwide Opportunities Fund. He holds a portfolio of investment trusts trading on interesting discounts. Buy in, and you will find yourself with a hefty exposure to property in Berlin via two of his holdings (Taliesin Property and Phoenix Spree Deutschland) but you'll get nice bit of India in the mix as well: nearly 5% of the fund is invested in the India Capital Growth Fund for which Mr Greenwood tells me he has "high expectations".

With a bit of luck, the returns will be good enough over the next six years for us all to ride on a bullet train.

This article was first published in the Financial Times

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

13 ways to get a tax-free income every year

13 ways to get a tax-free income every yearMillions more people are paying income tax as a result of frozen thresholds. But there are still more than a dozen ways to generate an income legally without handing over any of it to HMRC.

-

When is the Spring Statement and what's expected in it?

When is the Spring Statement and what's expected in it?The Spring Statement might have less of an impact than the Budget, but the annual fiscal event is still key to understanding what is happening in the UK economy and where it’s headed

-

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fire

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fireIndian stocks pass a new milestone, but global fund managers are holding back. Are there signs of overheating?

-

Shining a light on India

Shining a light on IndiaAdvertisement Feature Despite some short-term challenges, India remains very attractive for investors. Here’s why.

-

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?Briefings India has come a long way since independence to become the world's fifth-largest economy. But early mistakes and now a divisive leader are holding back the economy’s potential.

-

Investor optimism ebbs in Indian stockmarkets

Investor optimism ebbs in Indian stockmarketsNews India’s BSE Sensex stockmarket index has fallen by almost 8% so far this year. Interest rates are on the rise, and foreign investors have been selling up.

-

The best markets in Asia and how to invest in them

The best markets in Asia and how to invest in themCover Story China and Indonesia should do well over the next year, while India and Vietnam have exceptional long-term prospects. From tech giants to banks, there are plenty of cheap stocks, says Rupert Foster

-

The Brics never lived up to their promise – but is now the time to buy?

The Brics never lived up to their promise – but is now the time to buy?Analysis Twenty years ago hopes were high for Brazil, Russia, India and China – the “Brics” emerging-market economies. But only China has beaten expectations. Max King explains why and asks if now is the time to buy.

-

India: the next global growth engine

India: the next global growth engineNews India's stockmarket is booming, up by 37% so far this year, and the BSE Sensex index has delivered an annualised return over the last five years of more than twice that of the FTSE 100.

-

Forget China, here’s why you should invest in India

Forget China, here’s why you should invest in IndiaTips As China becomes increasingly hostile to investors, India, with a young, educated, tech-savvy population and a reform-minded government, is becoming an emerging-market favourite. Merryn Somerset Webb picks the best ways to invest.