How to profit when the gilt bubble pops

An ugly monster of a bubble could be about to burst in UK government bonds. Tim Bennett explains how spread betters can play it.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

An ugly monster of a bubble could be about to burst. And unlike the late 1990s dotcom bubble, this time it's in a dull, grey market associated more with crusty civil servants than flash entrepreneurs in pinstripes. I am talking about the market for UK government IOUs, or gilts. When this market blows up take cover. But set up the right spread bet first.

First, a quick bit of jargon gilt yields. In short, this is the annual expected return over the current price. Since most gilts pay a fixed income, the higher the price, the lower the yield. Earlier this month, yields hit a 300-year low. In a nutshell, that tells you that gilt prices are sky high. Why?

Three reasons. First, gilts are seen as safe in times of trouble. Pension fund investors in particular have piled in seeking a safe haven from global turmoil (after all, the UK government carries the highest AAA rating). Second, there are not enough of them around. Gilt auctions (where these IOUs are issued by the government) tend to be oversubscribed, and have been for years as pension funds scramble to find an asset that will pay for their obligations to retirees. Third money printing. In a bid to rescue a moribund economy the Bank of England has been merrily printing money via quantitative easing. Some of that money has been used to buy back government IOUs over the last few years, decreasing the supply and pushing up the price even more.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So what could change? Well, the latest jobs data from the US suggests things have stabilised there -at least for now. Meanwhile, in Europe, the fact that Italian bond yields plummeted after the ECB intervened to prevent a full-blown Italian debt default, suggests there's hope the eurozone's sovereign debt woes can be managed, even if the underlying structural problems remain. Next investors have piled into gilts reckoning the UK is a decent bet while the rest of Europe grapples with its sovereign woes and the ongoing Greek crisis.

But as soon as there is even a glimmer of hope, why would these same investors stay in an asset that pays well below the rate of inflation? The merest hint that risk appetites are back (stock indices such as the FTSE 100 have climbed steadily for most of the month) could see money rush for the gilt safe haven exit and see gilt prices crash. If so, what can a spread better do?

Enter the long gilt future spread bet. This is in effect a bet on gilt prices, via the associated futures contract (for more on futures see my video: What are futures?). Here's how it works.

Let's say your broker is quoting a price of 11,692-11,695 for the March long gilt futures contract (this equates to prices for the underlying gilt of £116.92 and £116.95 per £100 nominal). You decide gilt prices are about to fall. So you sell at 11,692, placing a bet size of £10 per point (you can bet less, with a typical minimum being £2). You are proved right and the spread falls to 11,672-11,675. If you buy back the spread and close out, you make a profit of 11,692-11,675, or 17 points. That's £170 at £10 per point, all tax-free.

To cap losses should the bet backfire, you can ask for a guaranteed stop this should only widen the initial spread by aroundthree points.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026

-

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continue

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continueIt was another difficult year for fund inflows but there are signs that investors are returning to the financial markets

-

Investors dash into the US dollar

Investors dash into the US dollarNews The value of the US dollar has soared as investors pile in. The euro has hit parity, while the Japanese yen and the Swedish krona have fared even worse.

-

Could a stronger euro bring relief to global markets?

Could a stronger euro bring relief to global markets?Analysis The European Central Bank is set to end its negative interest rate policy. That should bring some relief to markets, says John Stepek. Here’s why.

-

A weakening US dollar is good news for markets – but will it continue?

A weakening US dollar is good news for markets – but will it continue?Opinion The US dollar – the most important currency in the world – is on the slide. And that's good news for the stockmarket rally. John Stepek looks at what could derail things.

-

How the US dollar standard is now suffocating the global economy

How the US dollar standard is now suffocating the global economyNews In times of crisis, everyone wants cash. But not just any cash – they want the US dollar. John Stepek explains why the rush for dollars is putting a big dent in an already fragile global economy.

-

The pound could hit parity with the euro – but if it does, buy it

The pound could hit parity with the euro – but if it does, buy itFeatures Anyone visiting the continent this summer will have been in for a rude shock at the cash till, says Dominic Frisby. But the pound won't stay down forever.

-

Gold’s rally should continue

Features Matthew Partridge looks at where the gold price is heading next, and what that means for your online trading.

-

Prudent trades in Prudential

Prudent trades in PrudentialFeatures John C Burford shows how his trading methods can be used for more than just indices and currencies. They work for large-cap shares too.

-

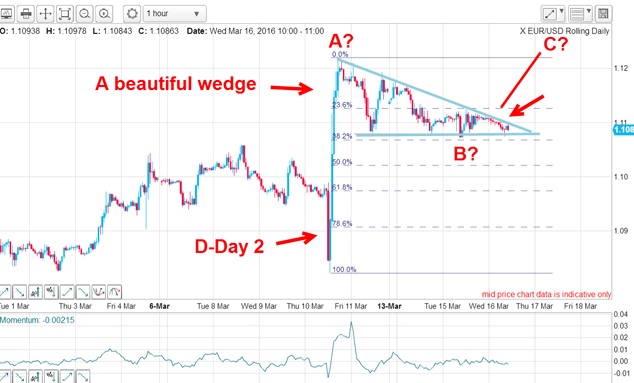

Did you find the path of least resistance in EUR/USD?

Did you find the path of least resistance in EUR/USD?Features John C Burford outlines a trade in the euro vs the dollar in the wake of the US Federal Reserve’s most recent announcement.