Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

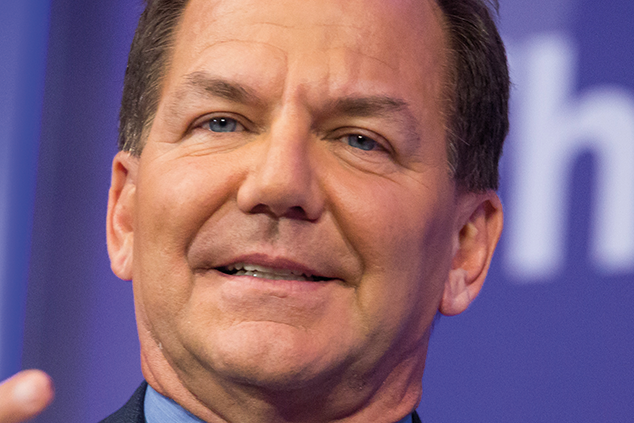

When Robert Rubin left the US Treasury in 1999, he achieved the rare distinction of being almost universally garlanded with praise. "Bob has been acclaimed as the most effective Treasury Secretary since Alexander Hamilton," observed President Clinton at the time. "And I believe that acclaim is well deserved."

Acolytes lined up to hail the former Goldman Sachs trader for presiding over the largest post-war expansion in American history. President Obama's economics team, notes The New York Times, was almost entirely comprised of "Rubinomics" disciples.

"Rubin's knack for spreading wisdom and tranquility has been the defining trait of his professional life," says Bloomberg Businessweek. But "just how wise and thoughtful" is he really? The fact is that the architect of the great American boom was also a leading originator of the chaos and destruction that followed.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Rubin waved through the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, paving the way for banking institutions that were "too-big-to-fail"; he failed to tame the "wild expansion of over-the-counter derivatives"; and when the crash finally came, he walked away with $126m from the technically insolvent Citigroup (see below). "Nobody on this planet represents more vividly the scam of the banking industry," says Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of The Black Swan. Rubin is "the Teflon Don of Wall Street".

That assessment is all the more powerful given that Rubin's "selflessness", whether in economic policy or day-to-day management, is a frequent theme of his admirers. Inclusive of, and quick to apologise to, underlings, his favourite pursuit is fishing and he has the philosophical personality to match, says Fortune.

By Wall Street standards, he was always an outsider. Raised in Miami Beach, he excelled at Harvard and was considered "intellectual" by classmates at Yale Law School. But he was so "laidback", says one, that the idea he would end up at "hard-charging" Goldman Sachs, let alone rise to the top, "would have seemed demented".

Yet, on joining the bank as a junior arbitrage trader in 1966, Rubin's quiet demeanour and trading prowess (honed by years of playing poker) immediately marked him out to his seniors as a potential leader.

Rubin stayed at Goldman for 26 years, and still refers to it as "the base of everything". But by the mid-1970s he was combining his role as one of Wall Street's "Four Horsemen of Arbitrage" (another was Ivan Boesky) with fund-raising for the Democrats. When he met Bill Clinton in 1991, they recognised qualities in each other, says Bloomberg: a "grasp of issues, intellectual curiosity, and an ability to listen".

"This is a guy as controlled as any human being I know," says a fellow Goldman arbitrageur of Rubin. "He's compulsively dishonest in a certain way, and compulsively honest in other ways." The description could have been written for "Slick Willy" himself.

How will history judge him?

David Rothkopf, an official in the US Department of Commerce during the first Clinton administration, recalls sitting in Robert Rubin's Treasury office in the 1990s and asking whether he had any regrets about dismantling finance industry regulations, says Megan Erickson on Bigthink.com. "Too big to fail isn't a problem with the system. It is the system," Rubin replied.

Yet there's plenty of evidence that, while those around him sang his praises, Rubin reached the end of his Treasury term with misgivings. In a 2003 Fortune profile, Carol Loomis quotes a friend who says that, in 1999, Rubin "thought the odds so plainly tilted toward trouble that he vowed he wouldn't dream of becoming a financial company CEO". Soon after, he joined Citigroup.

Rubin's tenure at the bank where he served as chairman of the executive committee and, briefly, as chairman of the board was hardly stellar, says William Cohan in Bloomberg Businessweek. "On his watch, the federal government was forced to inject $45bn of taxpayer money into the company and guarantee some $300bn of illiquid assets." Rubin's "serenity" came "to look a lot more like paralysis".

In his final years there, Rubin (apparently happily married to his Yale sweetheart) pursued a romantic affair with Iris Mack: a Harvard maths prodigy and former Enron employee. In a 2010 Huffington Post piece, she recalls asking what his role entailed. "'It means the word chairman' is in the title and I get paid very handsomely, but I don't have any actual managerial responsibilities.' He seemed pleased."

How will history judge Rubin? asks Cohan. His defenders claim he has been made a scapegoat. "People need people to blame," says Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, a former Treasury colleague. But others see him as symbolic of a rotten system. Nassim Nicholas Taleb wants systemic change to prevent what he terms "the Bob Rubin Problem" the co-mingling of Wall Street interests and the public trust "so people like him don't exist".

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

MoneyWeek is written by a team of experienced and award-winning journalists, plus expert columnists. As well as daily digital news and features, MoneyWeek also publishes a weekly magazine, covering investing and personal finance. From share tips, pensions, gold to practical investment tips - we provide a round-up to help you make money and keep it.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Paul Tudor Jones: stockmarket could go "crazy"

Paul Tudor Jones: stockmarket could go "crazy"Features Hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones, who predicted the October 1987 crash, believes the stockmarket will rally later this year, even in the face of tightening monetary policy.

-

Lex Van Dam: From reality TV to investment training

Features Lex Van Dam, a former Goldman Sachs trader turned hedge-fund manager turned reality TV impresario, has just launched his online trading academy.