Should you follow the crowd when investing?

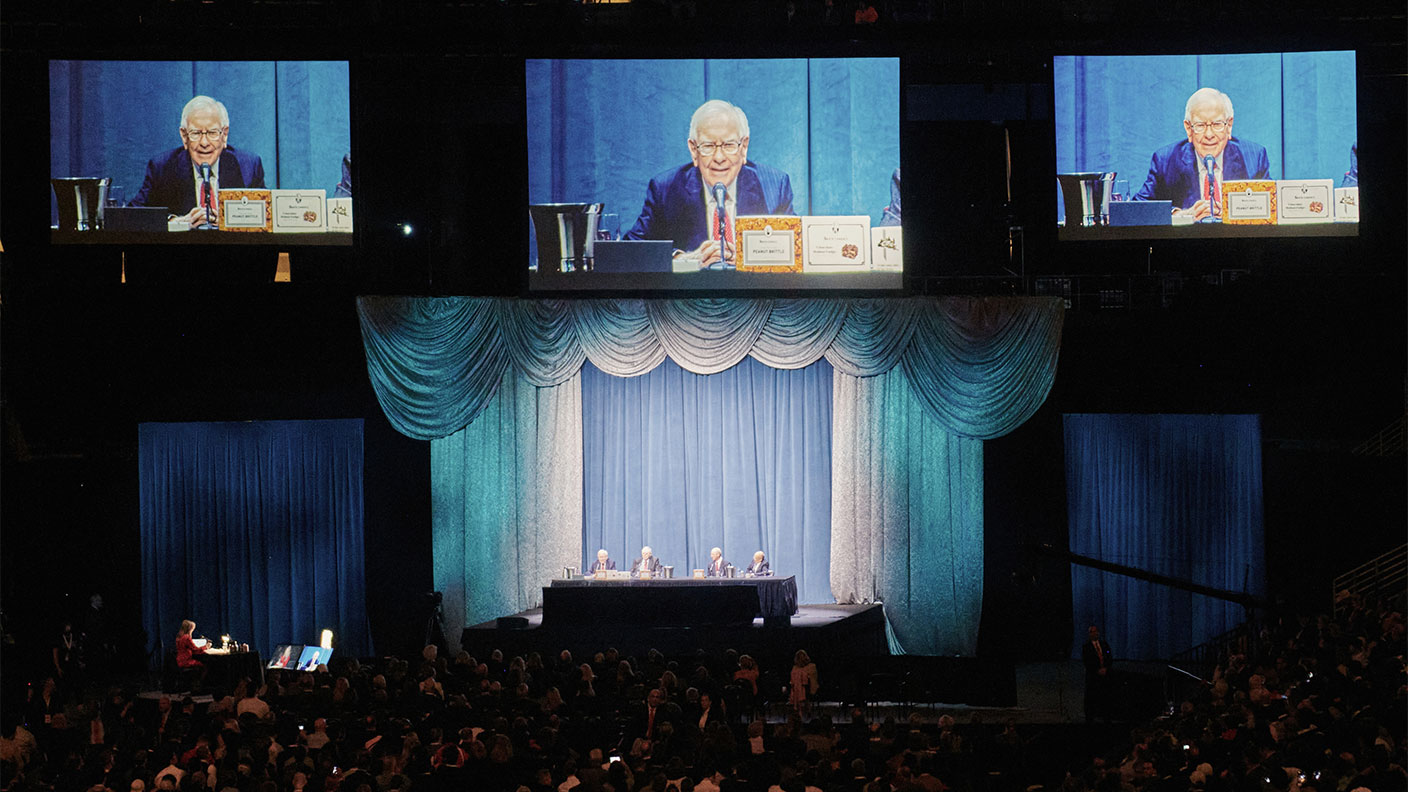

Warren Buffett famously said that going against the herd was the best way to make money on the stockmarket. But is following the crowd necessarily such a bad thing? Tim Bennett investigates.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Warren Buffett reckons the best way to make money is by being "greedy when others are fearful" and vice versa. But according to three professors at the London Business School (LBS), this is wrong. You're better off being greedy when others are greedy that is, you should buy the most popular stocks and sell the least popular. So are they right?

The case against momentum

Most investing strategies fall into one of two camps value or momentum. Value investors reckon the way to make money is to ignore the herd. The market is irrational good stocks sometimes get sold for silly reasons, and bad ones bought just because they're popular. So you should aim to buy the good stocks while they're cheap, and ignore everything else the market will come to its senses eventually. The trouble is, say LBS professors Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, that value investors may be wasting their time. As The Economist puts it, "the momentum effect is huge".

The trend might be your friend

Their study looked at the 100 largest UK stocks from 1900. They looked at the return generated from buying the 20 best performers over the previous 12 months, holding them and then adjusting the portfolio every month. The results are pretty conclusive. The strategy produced an annual average return 10.3% higher than a strategy built around buying the worst performers of the last 12 months. A pound invested in 1900 would have grown to £2.3m by the end of 2009 if this momentum strategy had been followed. Anyone buying "losers" in the hope they were unduly cheap would have ended up with £49 over the same period.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This effect seems to hold across other markets too. The trio applied their approach to 19 global markets and found "a significant momentum effect" in 18. It's not just stockmarkets. In currency and commodity markets prices can trend up or down for long periods. A Cass Business School study revealed 13 momentum strategies in commodity markets with an average annual return of 9.4% between 1979 and 2004. Sounds great. So why aren't we all momentum investors?

Time and effort

Momentum investing isn't as easy as it sounds. Following the Dimson, Marsh and Staunton stock strategy requires monthly portfolio rebalancing. That means selling some stocks and buying others to ensure you keep the 20 best performers. You could write a computer program to do just that. But even then you have trading costs to consider. Every time you buy shares you pay stamp duty tax at 0.5% of the price. Then, for a retail investor, there's the commission for trading say £6.99 for a regular trader, plus the gap between the bid and offer prices on the shares. As Cliff Asnes of hedge fund AQR Capital Management notes, momentum stocks are often of riskier, smaller firms, so these spreads could be significant. Then there's capital gains tax on any profits. The LBS report's authors say that these costs would not eat up an annual performance gap of 10% but for a retail investor they would certainly put a big dent in it.

When momentum goes wrong

The other issue is timing. Follow the herd at the wrong time and your losses can be huge. As Rob Harley of Bestinvest notes in The Times, the approach "does not work in all market conditions". Anyone who joined the late 1990s technology stock boom late got burned in 2000 when the market turned. Christopher Traulsen of Morningstar agrees: "Momentum investing thrives when market conditions do not change much, such as during the stockmarket's steady run between 2003 and 2007." But it's less useful "in more volatile conditions". In 2009, for example, anyone buying the winners of the previous six months would have lost around half their money, in both British and American markets. And as Andrew Allentuck warns in the Financial Post, it's also all too easy for investors to get caught up in the latest "Big New Thing", whether that is China, ethical funds, or tech stocks. The trouble is, "none are time-specific (no one rings a bell at the top) and none have anything other than relatively short performance periods to back them up".

What this means for investors

The fact that momentum exists means investors should think twice before paying for active fund managers. Shares benefit over short periods from a "bandwagon" effect precisely because many managers feel obliged to back trends. If they stand on the sidelines, they risk missing out on the decent short-term performance being enjoyed by their peers. By buying even when prices look toppy, there's less chance of being left in the bottom quartile. And if the market collapses, everyone gets burned together. That's why we advise sticking to cheap exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that track the market where possible you'll get similar performance, but it'll cost less.

When it comes to individual stocks we'd stick with value principles rather than chasing momentum it's too easy to buy at the wrong time. Pick quality stocks at decent prices and stick with them. You'll still benefit from spurts of price momentum, but will also cut your costs (no trading in and out of the market) and the risk that you pile into the latest fad at the top of an upswing.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

The UK regions with the highest proportion of homes above the inheritance tax threshold

The UK regions with the highest proportion of homes above the inheritance tax thresholdHigh house prices are pushing more families into the inheritance tax trap across the country

-

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek Talks

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek TalksPodcast Clare Francis, savings and investments director at Barclays, speaks about money and mental health, why you should start investing, and how to build long-term financial resilience.

-

Why we need a little patience

Why we need a little patienceAdvertisement Feature In volatile markets it’s easy to get spooked and sell your investments. But that could cost you many thousands of pounds. A patient approach can be much more rewarding.

-

The dangers of derivatives as the “Goldilocks era” ends

The dangers of derivatives as the “Goldilocks era” endsEditor's letter This is no longer a benign environment for investors, says Andrew Van Sickle. But – as the recent pension-fund derivatives blow-up shows – not everybody seems to have grasped that.

-

How Warren Buffett built his fortune

How Warren Buffett built his fortuneAnalysis Warren Buffett is considered by many to be the best investor of all time. We examine how much Buffett is worth and how he made his fortune.

-

A simple lesson from Warren Buffett that even children can learn

A simple lesson from Warren Buffett that even children can learnAnalysis Warren Buffett has an incredible investment record. And at the core of his strategy there is one very simple principle. Rupert Hargreaves explains what it is and how it can help you.

-

Why investors should beware of corporate waffle

Why investors should beware of corporate waffleAdvice When top executives try to retreat behind impenetrable jargon, investors should be very sceptical, says John Stepek.

-

A lesson for value investors from investor Howard Marks

A lesson for value investors from investor Howard MarksAdvice Value investors need to open their minds, says US investor Howard Marks. But why is he saying it now?

-

Why investment forecasting is futile

Opinion Every year events prove that forecasting is futile and 2020 was no exception, says Bill Miller, chairman and chief investment officer of Miller Value Partners.

-

What is value investing?

What is value investing?Value investing covers a broad range of bases, but the approach hinges on identifying companies that are worth more than their price suggests.