How to counter tax avoidance - raise VAT

Since people can't escape paying tax on the things they buy, raising VAT-levels could be a good way to cut tax avoidance and evasion - and bring in some extra money for the government too.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

With all the talk about how we need to raise taxes to deal with the deficit, combined with the general upset about tax avoidance and evasion, it seems odd that we hear so little about changes to the VAT system. We know that the main tax evasion takes place at the bottom and at the top of the financial tree.

Consider the bottom. A few months ago, Alice Miles, writing in the New Statesman,pointed to a study by an anthropologist working in a deprived area. He found that while the average official family income was around £4,000, thanks to unreported, cash-in-hand work, prostitution, bartering, trade in stolen goods and the smuggling of spirits, tobacco and drugs, it was actually more like £17,000. One in four people were "informally self employed."

Up at the top, there tends to be more avoidance than evasion clever accountants can manage all sorts of things. But the net effect is the same. Across the economy, there is a huge amount of income getting away from the taxman scot free. You might think that is ok at the bottom end but not at the top. Or vice versa. I think it needs dealing with at both ends.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

And VAT seems to be a good way of doing it. Think tank Reform looked at this last year and concluded that starting to charge VAT on food, children's clothes and to raise it from its current low levels on household utility bills would be better than raising any other tax. That's partly because they see VAT as less damaging to the economy as a whole than taxes on employment production and income. But also partly because this would make VAT less complicated and bring it into line with the VAT systems in most of the rest of Europe.

Finally, VAT is impossible to avoid (unless you live only on stolen goods). So the more it takes the place of income taxes the less overall avoidance/evasion there can be. The downside to broadening the VAT base of course is that it would hit lower income households proportionally more severely than higher income households. So you might need to fiddle with the income tax thresholds at the same time.

However, it might also be an idea to soften the blow by creating some kind of progressive VAT system. You could have a very low rate on food and essentials (with a higher rate on rubbish food such as ready meals and cake) and then bump the rate up as things turn from being needs into being wants and then into proper luxury goods.

This is how the tax operated in the 1970s (when it was first introduced). Then we paid 8% on standard goods and 12.5% on anything perceived as a luxury good. In 1975, Denis Healey imposed a 25% rate on real luxury goods (and electrical appliances). Doing something such as that again might not be particularly popular but doing it in tandem with a new low rate on food would at least address the problem that is vexing so many at the moment that of tax avoidance and evasion. If it didn't come with reductions in other taxes (which it should but probably wouldn't) it might also raise some much-needed cash for the government.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

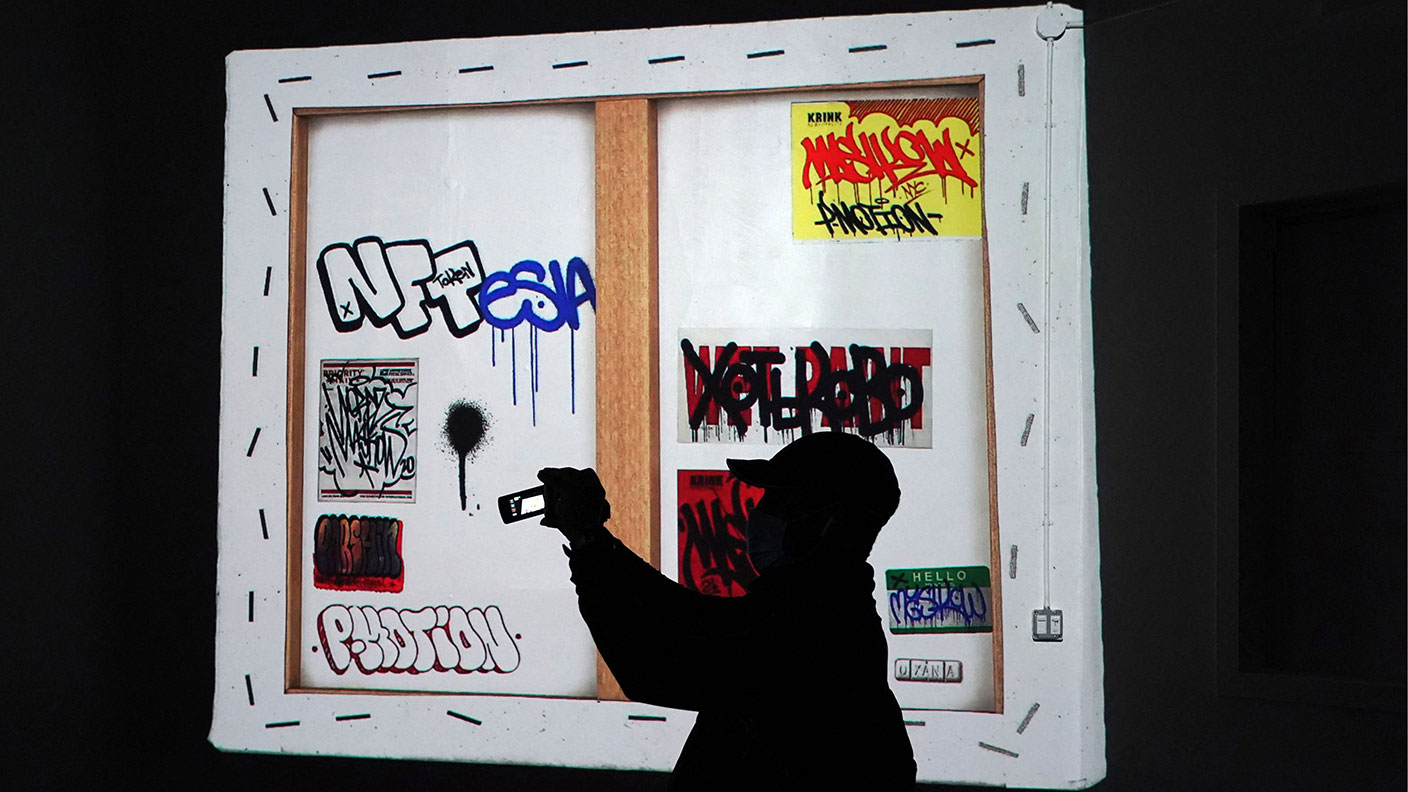

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.