Keep an eye on your fixed-rate savings bonds

Putting your savings into a fixed-rate bond is a great way of getting a good interest rate. But make sure you know the terms and conditions of your bond – and most importantly, when it matures, or you could end up losing out.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Putting your savings into a fixed-rate bond is a great way of getting a good interest rate. Anyone who locked up their cash a few years ago will have been enjoying great rates of return compared to what is on offer now. But make sure you know the terms and conditions of your bond and most importantly, when it matures.

When most bonds mature, providers move the balance into standard easy-access savings accounts, which tend to pay highly uncompetitive interest rates. So if you aren't on the ball and don't move your money to an account with a better interest rate, you could lose up to £1,000 a year in interest, reckons Moneysupermarket.com.

For example, Capital One's 2004 issue five-year fixed-rate bond, which was paying 5.85%, matures this month, and savers will see their interest rate drop by 5.1 percentage points, meaning a £15,000 deposit will earn £765 less in interest per year.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

And anyone who took out a one-year fixed-rate bond with Firstsave a year ago will see their interest rate fall by six percentage points on maturity, losing someone with a £15,000 balance £953 a year in interest.

But don't automatically assume you'll have to move your money. Some banks offer competitive rates on the savings account your money will be moved into. For example, when United Trust Bank's three-year fixed deposit account from 2006 (which paid 5.6%) matures, the money will be shifted straight into another fixed-rate account which is exclusive to existing customers and pays 4%.

So read the terms of your fixed-rate account and find out when it matures and what rate your money will earn after maturity. And if you need to switch, start shopping around. If you are prepared to tie your money up again, then Saga's three-year fixed-rate bond looks attractive with a 4.65% interest rate. The key benefit of this account is that, should interest rates rise and better deals appear during that period, you can withdraw your money early with only 90 days' loss of interest.

Ruth Jackson writes the weekly MoneyWeek Saver personal finance email. Sign up to MoneyWeek Saver here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Ruth Jackson-Kirby is a freelance personal finance journalist with 17 years’ experience, writing about everything from savings accounts and credit cards to pensions, property and pet insurance.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

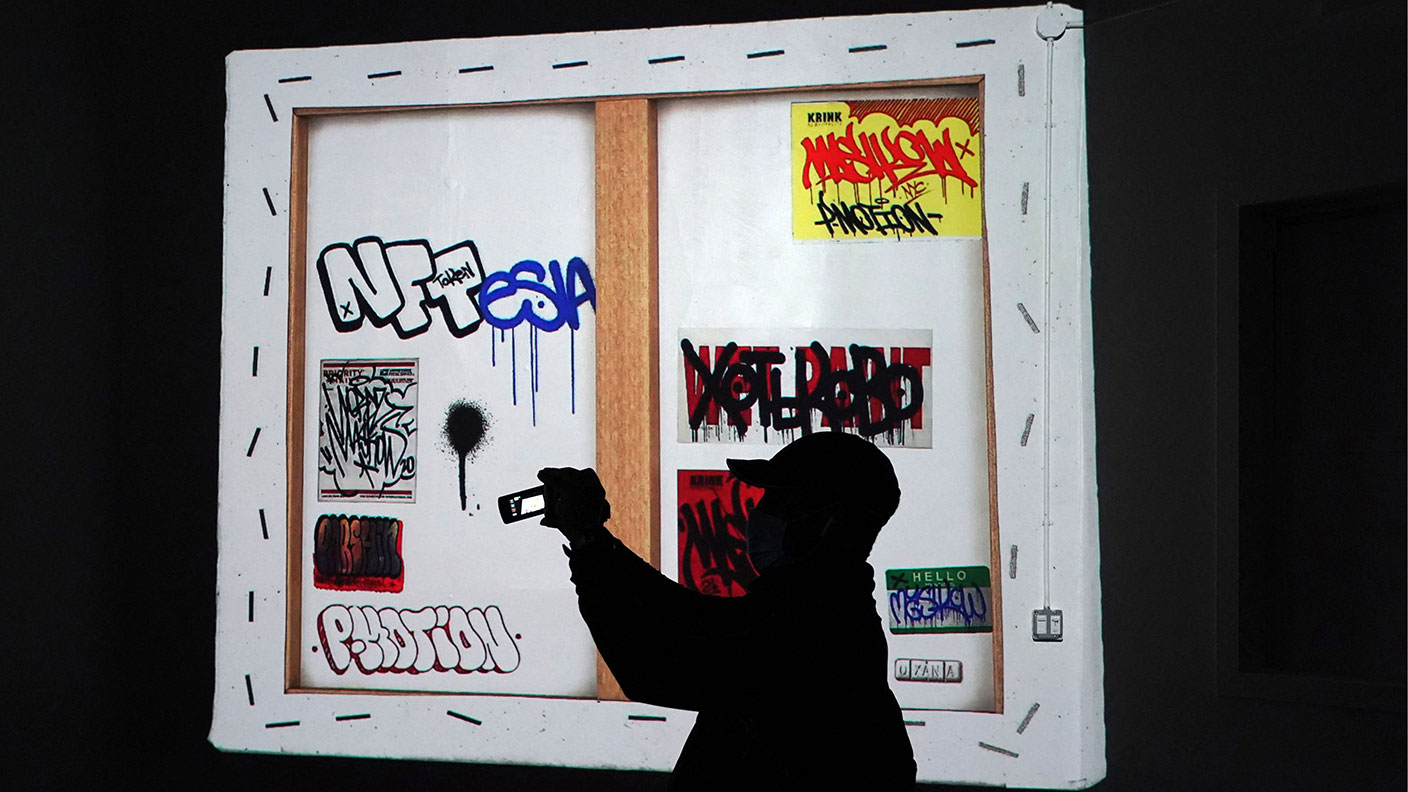

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.