How to invest in litigation finance – and get returns from bankrolling legal disputes

Lawsuits are a trillion-dollar business and litigation-finance firms play a key role in funding claims. The accounting can be complex, but there are opportunities for investors to profit, says Bruce Packard.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers,” says wise-cracking rebel Dick the Butcher in Shakespeare’s Henry VI. The line always gets a laugh – it’s easy to make jokes at lawyers’ expense – but Shakespeare is not endorsing the thuggish Dick’s view. On the contrary, it shows why legal suits are important as a non-violent mechanism for resolving disputes. Yes, when there are large sums of money at stake, disputes obviously take time, are unpleasant and stressful for both sides, and create large gains for lawyers. But the alternative would be a patronage system with violence as the ultimate dispute resolution mechanism. You don’t want to live in a country where the lawyers are killed.

Similarly, making money from legal claims may seem at first glance morally questionable. Champerty – which sounds like a picturesque Alpine village in the shadow of Mont Blanc, but is actually the practice of funding legal disputes – was banned in England from the 13th century until the 1960s. Champerty arose in the days when the country lacked an independent judiciary, so a nobleman might buy a weak claim and then through power, bribery or threat of violence convert it into an advantageous decision. Now that the rule of law is much stronger in England, allowing champerty favours a claimant who lacks the financial fire power to pursue a claim that they otherwise would not have been able to pursue on their own.

The size of the Western legal market is huge: the top 30 law firms have $2trn of pending arbitration claims, and annual law firm fees are $860bn globally, of which just over half is in the US. Both corporations and law firms expect the market to grow further as disputes rise following the pandemic, according to Ernst & Young. High stakes disputes are unavoidable, and it is better to find a way to profit from resolving them as fairly as possible than seek a return to medieval times.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This is where litigation-finance firms play a role. Aim-listed Burford Capital (the best known) and Litigation Capital Management offer non-recourse funding of legal claims in return for a share of the money recovered when the dispute is settled (non-recourse means that if the claim loses, the funder doesn’t get paid back). Other firms in the sector have different models. Manolete Partners specialises in recovering money from insolvencies and operates by buying cases outright. It then pursues company directors for the money they owe – usually because they illegally transferred cash or assets out of an insolvent business. AxiaFunder, a litigation-finance crowd-funding platform where I used to work, is unlisted, but offers investors the ability to invest in legal claims themselves, rather than buying shares in the operating firm.

Sharing the risks

One of the odd things about disputes is that the assets are valued differently depending on who funds them. A widget-bashing machine has the same value regardless of whether it has been leased or bought upfront by a widget-bashing company. But the value of the same claim is more likely to be recognised on a litigation specialist’s balance sheet than on a corporation’s balance sheet.

Christopher Bogart, chief executive of Burford, explained why this is at an investor day last year: “I was the general counsel of Time Warner, the media group. Time Warner’s business is about making movies and music. It’s not about generating positive cash flow from litigation claims. And as a result, it was both difficult for me to squeeze capital out of the chief financial officer to be able to put it to work in legal functions, and it was also not even particularly financially rewarding from a shareholder value perspective. My winning a nice, cash-generative case was treated by shareholders as a one-off gain, no multiple given to that and just tucked below the line. So it’s not surprising that companies… are regularly looking for ways not to have their litigation expenses running through their profit and loss.”

Funding or buying legal disputes is inherently risky – court judgments can go against you, even if your lawyers believe you have a strong case. If the owner of the claim loses, they (and the litigation funder) receive nothing and often the loser has to pick up the other side’s costs. Therium, an unlisted litigation finance company, has suffered a couple of high-profile losses. One involved a drunken bet made in the Horse & Groom pub between Sports Direct’s owner Mike Ashley and banker Jeffrey Blue – Blue lost and had to pay Mike Ashley’s costs. Another was the case brought by Amanda Staveley against Barclays over the bank’s emergency fundraising in 2008. Both cases highlight the risk in litigation finance: the outcome tends to be binary – either a large gain or zero.

However, over the last ten years, Burford has lost just 9% of its cases. It wins 29% in court, but the majority (62%) are settled before going to court. The average return on invested capital (ROIC) for a case that settles out of court is lower (48% ROIC) than if a case goes all the way to court and the judge rules in their favour (244% ROIC). I would expect similar numbers for the other litigation-finance companies.

It is the claimant’s decision whether to settle out of court for less money, or go to court and probably receive a higher reward but risk receiving nothing if the judgment is unfavourable. Hence, although the upside is greater from going to court, around double the amount of cases settle ($600m of Burford’s deployments), rather than going to adjudication (around $280m of Burford’s deployments).

Uncorrelated returns

A key attraction for investors is that legal disputes should be uncorrelated with other asset classes, such as government bonds or equities, which all respond to economic cycles. Disputes tend to be unique in nature, and should be uncorrelated with each other. Two high-profile cases illustrate this. Farkhad Akhmedov transferred assets to offshore structures so that he didn’t have to pay his ex-wife, Tatiana, a divorce settlement that she had been awarded by courts; Burford stepped in to help Tatiana pursue her claim against her former husband. Clearly, the successful pursuit of Akhmedov should be uncorrelated with one of Burford’s ongoing claims – against the Argentinian government over the expropriation of an oil company (YPF) a decade ago.

This is in stark contrast to other financial firms. Shares in asset-management companies rise and fall in line with swings in stockmarket indices. Credit-card companies report higher bad debts when unemployment rises. Banks all struggle at the same point in the economic cycle, particularly with lending secured against property and that’s why we have financial crises. Disputes, and hence the share prices of litigation-finance companies, are uncorrelated with unemployment, property cycles, or market swings.

That’s the theory and indeed the share-price performance of litigation funders has been uncorrelated with the market and within the sector. Since the start of the pandemic, Manolete is down by almost 50%, whereas Litigation Capital Management has risen 56% over the same time frame. Burford’s share-price performance is now flat since the start of the pandemic, although with considerable volatility (it peaked with a high of 970p and hit a low of 250p).

At first glance, the numbers look very attractive. Burford reports that it has generated a ROIC of 93% and an internal rate of return (IRR) of 30% on $962m worth of disputes that it has funded with its own balance sheet since 2009. Litigation Capital Management reports an even higher ROIC of 162% and an IRR of 79% over the last 10.5 years. The equivalent figures for Manolete are 167% and an IRR of 132% – the IRR is highest because insolvency claims specialists tend to see faster payback than the rest of the sector and IRR is an annualised measure.

As you would expect, high returns attract new entrants. The Association of Litigation Funders lists 13 members, including Burford, Harbour, Vannin Capital and Therium. Most firms remain confident that competition should not drive down returns, as this is a relationship-based business, with law firms tending to recommend the funders who they have successfully worked with in the past. That may be true, but it’s rare to find an industry where a large inflow of capital does not alter the economics of returns. Like banking and insurance, there will be a lag of several years between new business written and rewards (or losses) reported. Litigation funders who are writing business based on optimistic assumptions about returns can do so for several years before the chickens come home to roost.

Opaque accounting

A separate criticism is that these high reported ROICs are illusory and the sector has opaque accounting. It is important to understand that ROICs of around 100% that funders report are not comparable with the mid-to-high teens returns of companies such as Unilever. The litigation-finance companies report the ROIC on a portfolio of completed cases and exclude i) cases where money has been committed but not yet deployed ii) cases where money has been deployed or invested, but have not yet been settled and iii) allocation of their group operating costs. For Burford, group operating costs were $142m last year, which was higher than total income of $133m over the same period. Hence it can report a loss of $9m, but a cumulative ROIC of 93%. Remember also that Burford won a favourable settlement over the Akhmedova divorce, receiving $103m in cash in the second half of 2021 and $70m realised gain over the life of the investment. Without that, the results last year would have looked even worse.

Critics and management of the firms do not disagree on these numbers, but there is some dispute about how the numbers are presented. By way of example, Burford’s 93% ROIC calculation is based on $962m capital deployed in completed cases, from which it has recovered $1.86bn. Simple. Yet if we sum up all of the capital committed using the table on page 44 of the 2021 annual report, the sum comes to $3.5bn. The roughly $2.5bn difference represents those cases to which Burford has committed capital, but have yet to reach a conclusion. If we include those disputes then the ROIC turns negative. Should the denominator include all capital that has been committed, or just that invested in cases that have now completed? You can make the case for both calculations: what is important to understand is that the ROIC figures reported by litigation-finance companies are not comparable with companies in other sectors.

The wider point is that critics argue Burford is quick to write up gains with fair-value accounting, but slow to recognise losses and hence book value may be overstated. It’s hard to critique accounting from the outside, but we know that originally management were against writing up the value of assets using fair-value accounting. In 2010, Burford published a cash net asset value (NAV) figure, alongside the NAV measure required by statutory accounting standards, suggesting the former was a better guide to valuation. Then something changed. In the 2011 annual report, Burford stopped publishing cash NAV, claiming that cash NAV “has not been embraced by analysts and investors, and given the increased complexity in its computation… and the relatively modest and clearly identifiable unrealised gain in the portfolio, we do not intend to continue to use or publish it after this set of accounts”.

Voluntary disclosure – what companies choose to tell investors, rather than what they are required to reveal – is a fascinating area. Very often when companies change their mind and withdraw disclosure it’s even more significant, though harder to spot. Unless you are reading results laid out alongside the previous year’s figures, it’s hard to see what is no longer there.

Still, Litigation Capital Management uses historical-cost accounting, not fair-value accounting. It reports a higher ROIC than Burford, yet it has averaged a return on equity (ROE) of 11% over the last three years, according to SharePad’s data. Manolete’s ROE has averaged 26%, but is forecast to fall in the coming years. We can conclude from this that litigation finance could still be an attractive sector, but investors need to exercise judgement, since lawyers are experts at marshalling convincing evidence and overlooking information that doesn’t suit their case. “Equity aids the vigilant not the indolent,” as the legal maxim goes.

The case for and against Burford Capital

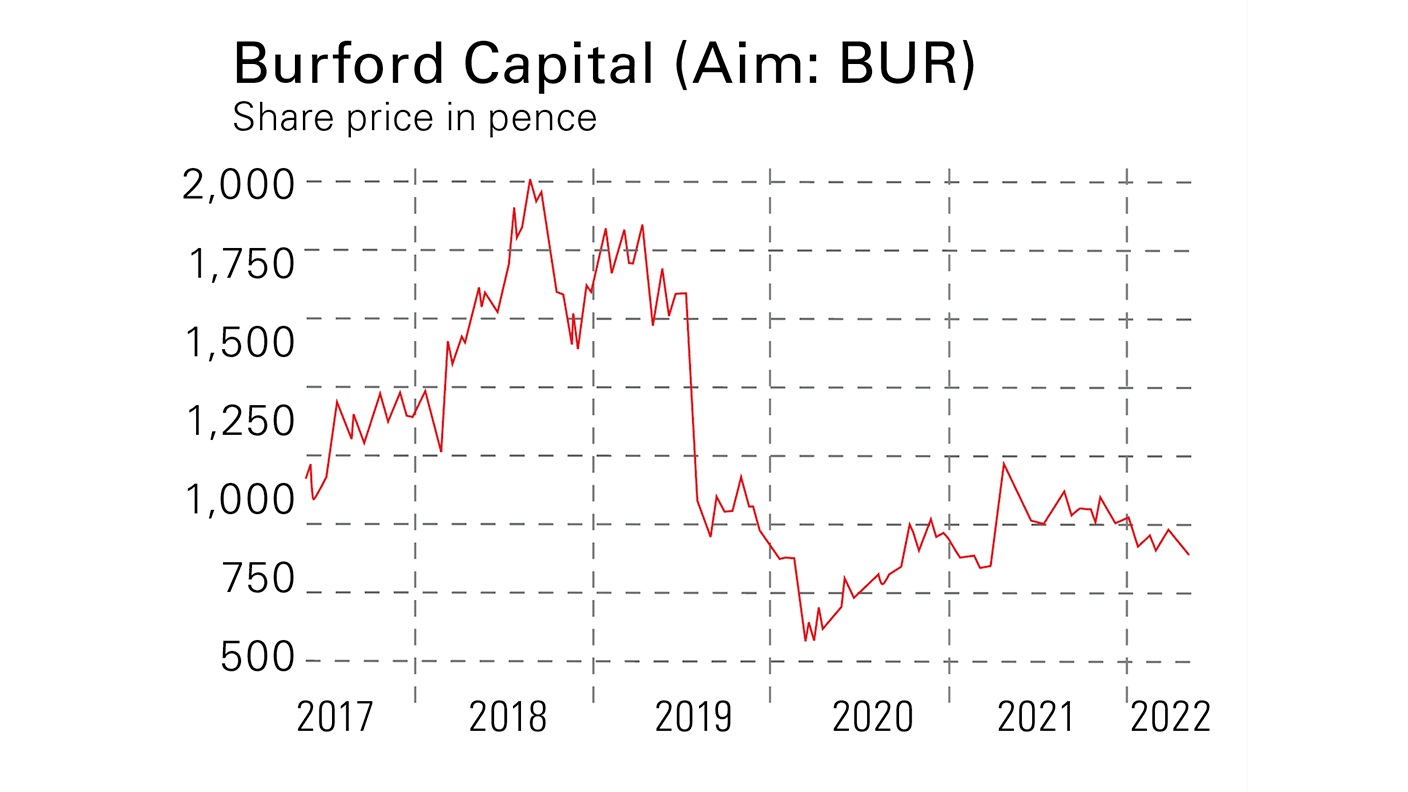

Burford Capital (Aim: BUR) floated in 2009. By October 2018, the shares had risen from £1 to almost £20, making it one of the best Aim initial public offerings of the decade, and Burford’s management raised £192m in additional capital at 1,850p per share.

Then in April 2019 the equity analysts at Canaccord Genuity published a sell note questioning Burford’s premium valuation. A few months later, Carson Block of Muddy Waters Research led an attack on the firm, calling it “a perfect storm for an accounting fiasco.” He compared Burford’s accounting to Enron and also highlighted the fact that the chief financial officer (CFO) was Christopher Bogart’s wife, Elizabeth O’Connell. (She was later replaced by Jim Kilman, formerly Burford’s investment banker at Morgan Stanley and now by Kenneth Brause, who was the CFO of US-listed lender OnDeck.)

The original sell note by the equity analysts didn’t gain much attention, but Block has made a name for himself shorting Chinese frauds: Orient Paper, Sino-Forest, Luckin Coffee. He has been aggressive and he’s been right in the past. Thus Burford’s share price slumped, falling below 300p in March 2020, helped by the broad sell off in markets.

Following the attack, Burford provided additional disclosure. It said it has written up the value of its case against Argentina for expropriating YPF to $773m. The firm’s rationale is that there is an established secondary market in this large claim: it sold 39% of its interest for $236m in a series of third-party transactions from 2016 to 2019. Management say that fair value-accounting requires Burford to write up the asset. That may be true, but it’s hard to square with its prior justification for why it no longer reports cash NAV (see above).

The shares have recovered somewhat and stand at 605p. The book value was $1.55bn at December 2021 (£1.2bn or 560p per share) versus a market cap of £1.4bn, implying a price to book value of about 1.15. Management reckon the portfolio excluding the YPF case could generate $3.8bn or around 1,340p per share – although it has around $1bn of debt.

It’s easy to see why the market has trouble valuing Burford, with it having traded as high as five times book value, versus 1.15 currently. Still, there are some catalysts coming up that are likely to move the share price significantly. Most notably, the YPF case has finished the discovery process. Burford expects summary judgment and we should hear more in June. There could be a judicial ruling without the case going to trial. If instead a judge rules a trial is required, then that should begin 115 days after the decision.

Burford’s shares are now dual-listed in New York. The firm has switched to US accounting standards and is also now recognising costs earlier (in line with fair-value gains), reducing near-term profits. By doing this, I imagine that management hope to facilitate comparisons with alternative-asset managers such as Blackstone, which trades on 9.5 times book value (although the latter mostly holds private equity and real estate). My view is optimistic and I hold the shares. Still, there is a risk that Burford loses the YPF case and investors question the value of the assets that it has been funding.

Bruce owns shares in Burford Capital and share options in AxiaFunder.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Bruce is a self-invested, low-frequency, buy-and-hold investor focused on quality. A former equity analyst, specialising in UK banks, Bruce now writes for MoneyWeek and Sharepad. He also does his own investing, and enjoy beach volleyball in my spare time. Bruce co-hosts the Investors' Roundtable Podcast with Roland Head, Mark Simpson and Maynard Paton.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.