Climate change: the price to pay for saving the planet

Environmental risks to our future are very real. There are four reasons to be optimistic, but all will have long-term consequences for the economy and financial markets, says Jonathan Compton

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

It’s confession time. I have finally come out as a fully-fledged tree-hugger. Aged ten, I planted my first tree (a eucalyptus), bought a polecat ferret (I had confused endangered polecats with polecat ferrets) and gave my first eco-donation to Save the Whales. These were not things to declare openly, being un-cool.

Later, like many people, I was sceptical over the more dramatic claims made by climate doom-mongers. But the simple observation of the loss of so many animal and plant species combined with visible environmental destruction forced me to accept that change is needed.

Remedial environmental action is long overdue, but my super-cynical City background makes me certain that government programmes have little chance of being effective. Yet there are four good reasons to be cheerful and to believe that the tide has already turned.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Population will peak soon

To state the obvious, the prime cause for planet-wide environmental problems is too many people. From one billion in 1800 to 2.5 billion in 1950 and now eight billion. The Old Testament solution of killing every first-born child would certainly work, but understandably is out of fashion. Yet it is becoming increasingly probable that peak population is less than a generation away. I have long watched United Nations and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forecasts shortening. In the 1980s the forecast peak was around 2150. In 2010, the peak was expected in 2120. Now the optimistic case is 2080. My guess is around 2055. Why so soon? Because the data is accelerating. Fifty years ago, the world’s population was growing at 2.3% per year. Now it is 1.1%. In 1960, women of childbearing age on average were having five children; now it is 2.47. The trend is for further, often sharp, declines in all continents (except Africa, and even there birth rates have peaked).

The reasons are not difficult to work out. First, wherever women have gained access to cheap or free contraception, the birth-rate tumbles. Secondly, the more that women have equal access to the labour market, the more the fertility rate falls. The third key reason has been urbanisation: birth rates are always substantially lower in cities. Other factors clearly include the rising costs of raising children and the inability of one working partner to earn sufficiently for the family, coupled with the understandable desire for a combination of a better lifestyle and consumer goodies. Although not proven, another probable reason is tumbling infant mortality rates. In the UK in 1900, the rate was a horrendous 228.1 per 1,000 live births. A quarter of all children never saw their fifth birthday. And the UK then was by many measures the wealthiest and most powerful country in the world. The rate now is just 0.4. Couples globally can expect their children will make adulthood, so fewer are needed.

The key measure determining the size of a country’s population is the replacement rate. Below 2.1 live births per female, the population shrinks. An ever-growing number of countries has joined this club. Japan is a well-known example. Its population peaked at 128 million in 2010. Since then, it has fallen by four million and is forecast to decline to 101 million by 2050. By then, more than a third (38 million) will be over 65, yet only 11 million under 14. True, these children will get great Christmas presents, but pensioners outnumbering children by more than three to one is a serious problem.

Other members of the shrinking population club already include Germany, Poland and Russia. By 2030 new members will include Italy, Spain, South Korea and China. We can be certain for two reasons. First, we know current fertility rates. Secondly, there has never been a prolonged period after fertility rates have fallen that they then reverse. Already, half the world’s population lives in countries where the fertility rate is below the replacement rate. That list continues to rise.

There are two less-discussed reasons why the decline will commence far earlier than the gurus expect. These are tubbiness and infertility. We know being seriously overweight affects life expectancy, health and productivity. Yet because food production has been extraordinarily efficient, it has more than kept up with a rising global population and become far cheaper as a percentage of income. A single UK example suffices to demonstrate the weight problem that applies globally. Approximately 20% of five-year-olds starting school are overweight or obese. Here they are fattened-up, so that by age eleven, the percentage doubles (in 1970 it was 5%). Moreover in no country have national weight-loss programmes ever worked on a long-term basis. Life expectancy rates for British children born after 2000 are lower than for their parents. It’s rather shocking.

Infertility is poorly researched, but the consensus from spotty data is clear: it is rising rapidly. Infertility now affects 15% of all couples in developed countries, double the level in 1992. The reasons are unknown, but likely to be a broad combination of factors from weight to chemicals in processed food, pollution and lifestyle. Rising infertility and heftiness problems are simply not built into population projections.

Why insurers will save us

There is an old City adage that “only cockroaches and insurance salesmen will survive nuclear winter”. This reflects that none of us like to pay often considerable amounts of money to protect against an unlikely event. But insurance has had a huge role in innovation and saving lives and may yet help to save the planet. Since the early 19th century, ships could not obtain insurance unless they were sound and carried chronometers (to know where they were). Fire insurance for buildings compelled better building practices. Life-insurance premiums for smokers are considerably higher.

Most obvious of all has been the role of insurance in automobiles. In January 1983, seatbelts were made compulsory in the UK. There was a widespread howl – often from lawyers – that this was a gross infringement of personal liberty. Offenders frequently avoided successful prosecution through a range of ruses winked at by judges (on the “boys will be boys” principle perhaps). Step forward the insurance companies. They refused to pay out in full for cases where the injured driver was not wearing a seatbelt, on the basis that he had voluntarily made his injuries worse, known as contributory negligence. After a while, the courts went along with the logic of this argument. Many lives were saved, and injuries lessened.

In 2016, the government created a new reinsurance company called Flood Re to cover those homes built before 2009 in areas at high risk of flooding. Insurance companies mostly fund it themselves, but we all pay for this via a levy on our home-insurance policy. The number of homes believed to be at risk was a maximum of 250,000 (businesses were not covered by the scheme). Today, the Environment Agency believes more than five million homes and businesses are at risk of flooding. This number could double by 2050 if current planning laws remain unchanged. Developers like flood plains: they are flat, foundations are easier to build and the profit margins are better. Parliament has been angsting about building on flood plains for over a decade, but has done very little, save giving the Environment Agency greater funding for flood prevention.

There are two obvious responses. Building on flood plains is simply very stupid (as are the buyers) and building ever greater flood defences pushes the problem downstream. Flood plains exist to alleviate flooding, not as sites for urban sprawl. This year, many home owners have been genuinely shocked by the increase in their premiums as flood risks are re-assessed. For an increasing number, the cost of flood insurance is becoming unaffordable and their homes less saleable. The same is happening in flood-prone areas worldwide. Once again it is the insurers forcing change, rather than governments. Thus, it does not take a leap of imagination to see that insurance companies will refuse to cover – or demand government subsidies for – a host of increasing environmental problems.

Ask most people the purpose of an insurance company or bank and you will get woolly answers such as paying you for an injury or holding your money safely. Their sole purpose is to make their shareholders money. This is relevant because of rising catastrophe losses, which are bleeding many insurance companies. Between 1970 and 2000, the largest weather-related catastrophe loss year was 1999 at $44bn. Over the last ten years, the average was over $80bn. The number of record years increased in frequency, with 2005, 2011, 2017 and 2021 varying between $101bn and $152bn. The response is therefore predictable. Firms are refusing to insure at any cost in some areas and raising premiums to eye watering levels in others. Slowly, those luxury holiday huts on sun-drenched coral reefs – the environmental equivalent of Conan the Destroyer – will be unable to get cover to operate.

In praise of vegetarians

Even more unexpected saviours of the planet are vegetarians. I apologise here for a necessary raft of numbers. The world is 71% ocean and 29% land. Of this land, 70% is habitable. The amount occupied by buildings, rivers and lakes is tiny at 2%, while scrub land accounts for 11%. Just over a third of the land area is forest (down from half in 1900). However, the key number is that half of all habitable land is used for farming. This is an ecological disaster. The lesser part is that many farm practices – from slash and burn in Asia and the Amazon basin to chemical/ploughing intensive agriculture in developed countries – is now known to be extremely harmful in climatic, ecological and sustainability terms. The greater reason for farming being harmful is the demand for meat.

I am not going to lecture on the virtues of pulses and prunes, because I am not sure I want to live without fillet steaks, hamburgers and dover sole. But three-quarters of all farmland is used directly or indirectly for meat production, livestock and dairy. It takes around seven tonnes of feed to make a tonne of beef, which is highly inefficient. If meat consumption were halved, or reduced in preference for animals with better conversion rates (pigs are about 3.5:1, chickens below 2:1) then the amount of land used for agriculture could be reduced by a third. The equivalent of one-and-a-half times the size of Europe could be returned to forest or savannah – good for many reasons, including flood prevention, air quality and species recovery.

Will this happen? No. Moreover the data is occluded by multiple lobby groups using made-up statistics, but according to the UN, meat consumption globally fell for the first time in 2019 after decades of steep rises. In most countries (excluding those with a largely meat-free diet such as India) vegetarianism is on the rise, while flexitarians – limited meat and dairy products – are rising at a very fast rate.

The role of rebellion

My final unexpected saviours are not popular because of their deliberate disruption, but I confess to some sympathy for Extinction Rebellion and related groups popping up all over the world. It takes considerable bravery to glue your buttocks to the middle of a busy motorway or your nose to the top of a locomotive. Although their politics are often inchoate or plain bonkers, they are an important catalyst to keep governments to commitments. The last general election witnessed astonishing tree inflation. The Conservative government promised to plant 30 million a year, the Scottish National Party pledged 60 million. Both are missing their targets by canyon-wide margins. (Labour was two billion by 2040, Lib-Dems 60 million a year). Even if attained this would be a lower planting rate than 1950-1990. The rebels hold politicians’ feet to the fire.

I am optimistic that changes in demographics, insurance, farming, food and minority agitation can reverse the clear threats to the environment (and thus to us all). This will be hugely disruptive and bad for many areas of stockmarkets. Ageing populations tend to sell equities and environmental business costs are set to soar. Pensions and healthcare for many will either shrink or be unaffordable. Current problems will be turned upside down: developed countries may urgently be seeking more young labour, which can be met only by immigration. Developing countries may be especially hard hit as their under-developed pension, welfare and health systems will fail to deliver what their populations expect. The optimism that robots and technology can provide all the answers seems a stretch.

The bottom line is immediately unattractive, in that real incomes are unlikely to rise much, if at all. Wherever a national work force has shrunk, so income per capita has tended to be static or decline. The political fallout must be considerable, although impossible to forecast – but uncertainty is never good for markets. Yet far better these saviours than the alternatives. Meanwhile, I have just placed my 2022 tree order.

Five ESG-friendly investments

When the American robber Willie Sutton was asked why he stole from banks, he simply replied: “Because that’s where the money is.” Similarly, asset managers have raced to re-brand themselves as generally very nice and responsible. In the fourth quarter last year alone, environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds globally had net inflows of $142.5bn. Yet according to an independent report by think-tank InfluenceMap, 421 out of the 539 largest funds are not aligned with the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. In the UK, a mere 12 from the top 200 by size have a neutral or positive score. I will focus on some that do.

Merchants Trust (LSE: MRCH) is the second-best performing UK equity income fund over the last five years, with a total return of 61%. The portfolio is “conservative”, the ongoing charge 0.61% and it yields 4.8%. At a tiny 1.7% premium to net asset value, what’s not to like?

In the open-end fund category, the Janus Henderson Global Sustainable Equity Fund has been a laggard over the last 12 months, but its three and five year numbers are top quartile. My main caveat is current weightings: 60% in America and 42% in technology. Hopefully, the manager will see the error of his ways. BlackRock has a better record than many asset managers of trying to be environmentally friendly. The BlackRock Continental European Income Fund gives broad pan-European exposure to companies meeting most ESG rules. Performance has been second quartile, but the outlook for European equities looks reasonable so the rising tide should help future returns.

Waste management, water treatment and recycling are all growth businesses. In the UK, loss-making Biffa (LSE: BIFF) is a leading waste collection and management business that should return to profits this year. Mid-sized, with a £1.1bn market capitalisation, its future depends in part on how well it integrates recent acquisitions.

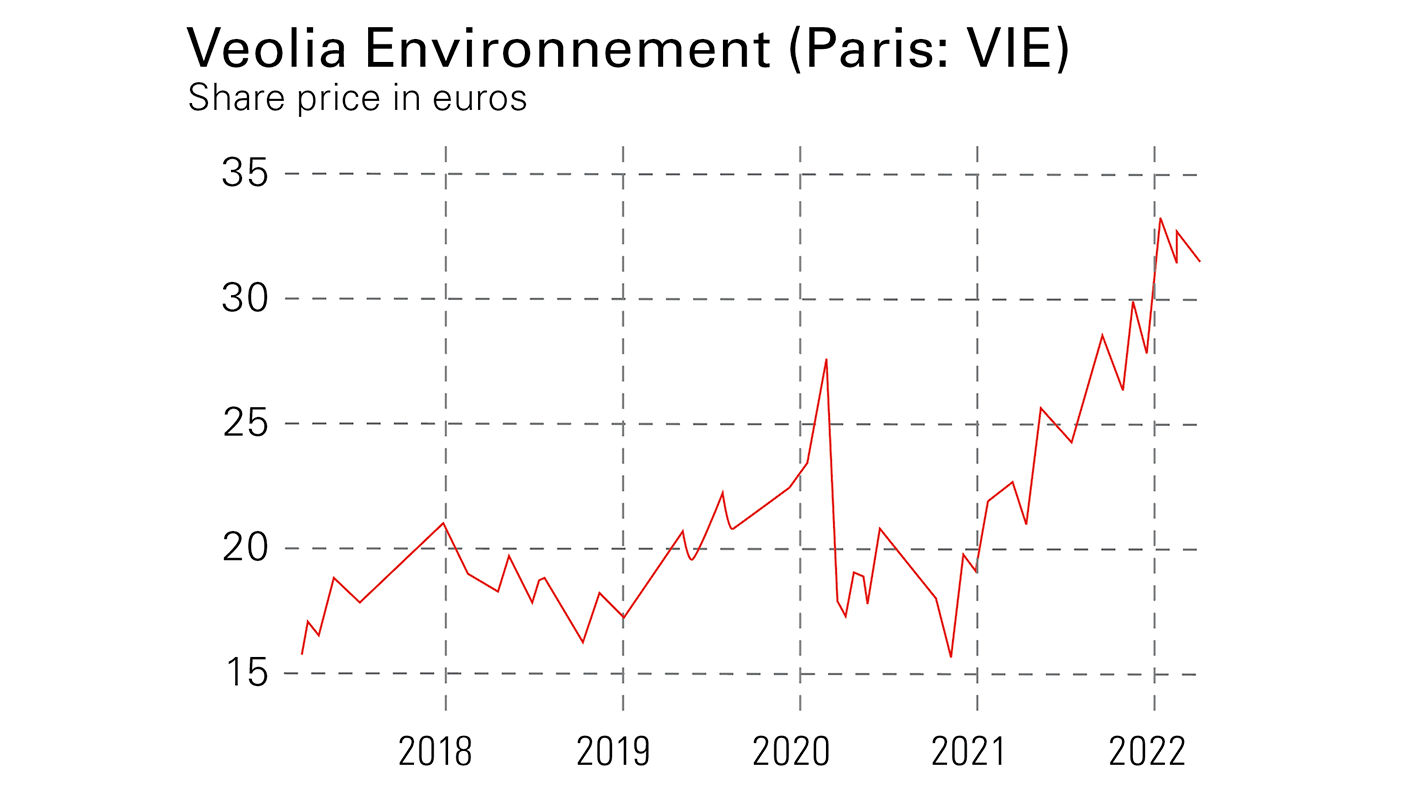

For the global big league, look to France’s Veolia Environnement (Paris: VIE), a €23bn company that I have recommended before and wish I had bought then 50% cheaper. It designs and supplies water and waste management solutions, from sewage treatment and waste collection to providing clean water and purification. There is also an energy consulting business. Veolia has been expanding steadily worldwide and is an undoubted leader. It recently acquired a French competitor, Suez, but the takeover looked reasonable value (unusually, given the history of takeovers) and seems a good fit.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jonathan Compton was MD at Bedlam Asset Management and has spent 30 years in fund management, stockbroking and corporate finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton