How to profit as luxury goods keep booming

Luxury goods is an industry that thrives on conspicuous consumption. It's had a surprisingly good pandemic, and there are plenty of reasons to expect that to continue as it taps into younger consumers.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“Without basic bitches like me, you wouldn’t be fashionable,” Emily Cooper, the trendy young American marketer, tells stuffy French fashion designer Pierre Cadault in the popular Netflix series Emily in Paris. The exchange illustrates the tensions in the luxury goods sector, because – as Emily suggests – it is “basic bitches” like her that are now driving the market. The world of luxury is changing, whether Cadault likes it or not, and investors should take note.

To understand how and why, we first need to thumb through our millennial dictionary to discover just what is a “basic bitch”. One definition comes from a 2014 New York magazine article as “a terminally boring Sex and the City viewer and consumer of pumpkin-spice lattes”. (Screenwriter Darren Star created both Sex and the City and Emily in Paris.) In terms more polite and familiar to MoneyWeek readers, a basic bitch is a young mass consumer – a buyer and follower of trends, tastes and fashions that are just as likely to have been scooped up from the pages of Instagram as from the pages of Vogue. But a buyer nonetheless, armed with a Mastercard and ready to use it.

In decades past, fashion houses revelled in their snootiness. They encapsulated the haughtiness of haute couture. Many, such as Chanel, still do. The club is so exclusive, in fact, that the term haute couture in France is strictly controlled by the French Ministry of Economy and Finance as if it were a fine wine. If your fashion label wants to call itself haute couture, your atelier must be in Paris, employ at least 20 people and make custom clothing for private clients. Even then, you must be waved through by the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture (even though the father of haute couture was a 19th-century fashion designer, born in Lincolnshire, called Charles Frederick Worth). Your mystique lies in the exclusivity of your wares. The more you put up your prices, the more people want them. They are Veblen goods, named after the Norwegian-American economist Thorstein Veblen, who pointed out the phenomenon. And consumers want them, precisely because most other consumers (we imagine) can’t have them. Owning them is a visible sign of our success.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Triumph of the parvenus

But is there anything so grating for the old guard as the sight of parvenus – the newly minted masses – flaunting their success, whether real or as plastic as their preferred method of payment? It’s classless in the senses of taste and social hierarchy. Parisians watching the first season of Emily in Paris were aghast to see “their city caricatured by American screenwriters little inclined to realism”, says regional French newspaper Nice Matin – as if realism had ever been the city’s main selling point. There is a name for the condition that afflicts tourists sold a romantic ideal only to come face-to-face with blunt realism. It’s called Paris syndrome.

But then, the world of high fashion has always been about selling an image of success and generations of consumers have literally bought into that. If you want to be at least seen as successful, then you have to dress for the part. And that costs money. If owning a Louis Vuitton handbag is what it takes to live your #BestLife, then who is to say any different? So it’s no wonder, then, when confined to our homes over the past couple of years, unable to spend on dining out or on holidays, consumers went online for a little retail therapy.

Before the pandemic, some fashion labels had avoided selling over the internet. E-commerce is grubby, the online equivalent of TK Maxx; more high street than Bond Street. Imagine buying a Dior dress from Amazon – or worse, one that had been discounted. Then Covid-19 arrived. Big spenders stopped visiting the boutiques and sales rooms of Mayfair and Manhattan. For the first time, Patek Philippe held its nose in allowing retail partners to sell its watches online, according to the Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2021 report from accountancy firm Deloitte. Rolex and Chanel’s fashion line couldn’t even bring themselves to do that. But then, those two companies are privately owned. Hugo Boss, which is listed on the Frankfurt stock exchange, has shareholders to appease. When the pandemic hit in 2020, sales dived as it closed around 1,000 outlets worldwide. Its customers suddenly had no need for its range of formalwear. Currency adjusted online sales at Hugo Boss, however, grew by 49%, with its casualwear range performing strongly. Internet sales have taken over. New York-listed, British-based ecommerce site FarFetch was the fastest-growing of the top 100 luxury goods companies mentioned in the report, doubling sales during 2020, by not only buying up brands, but also providing the ecommerce platform to sell them and others.

Luxury goods companies were particularly well-placed to weather the storm for several reasons, among them the cachet of the brands. You don’t just create a status symbol overnight. There is no watch “like” a Rolex; a Rolex is a Rolex or it isn’t. And that gives these companies wide economic moats against challengers. If a celebrity is snapped on the red carpet wearing your dress, that helps to build your brand, which is why fashion labels are often so keen to lend their creations to the stars. But it still takes time, and fashion being the fickle thing it is, a little bit of luck too. Brands such as Dior and Chanel have been able to do what they do for decades, because, in the minds of their followers, nobody else does it quite like them. Their dresses ooze timelessness. Their styles are their own and their creations unique.

Solidly profitable

Luxury brands also have a greater immunity to price pressures and inflation. Their margins are high, and they can put up their prices, because that is what their deep-pocketed customers already expect. It’s one thing for the cost of your weekly supermarket shop to rise by 5.5% in a year (the annual rate of consumer price inflation in Britain in January). It’s quite another for your shoes to rise by that amount – or more. A Chanel classic flap bag now costs £6,630, 40% more than in early 2020, notes Lauren Indvik in the Financial Times.

The top 100 luxury goods companies by sales generated revenues of $252bn in the 2020 financial year, according to Deloitte, down from $281bn in the previous year. And yet, more than half of these firms stayed profitable, with 13 companies reporting double-digit net profit margins. The biggest players, led by LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, Kering (which owns Gucci) and Estée Lauder, also dominate the list. The top 15 firms with luxury goods sales of over $5bn generated 63% of the sales total.

Clearly, it helped that unemployment remained relatively low in the West, thanks in no small part to government furlough schemes, and central bank money printing on a vast scale. American consumers even had a collective $395bn placed directly in their bank accounts, ready to spend at the click of a mouse. Then in 2021, the industry came “roaring back, experiencing a V-shaped recovery”, says consultancy firm Bain & Company. The market grew by 29% to $324bn and by the end of the year, it was even 1% bigger than in 2019, before the pandemic. Sector stocks rose 40% year-on-year, outperforming the wider stockmarket for the sixth year in a row. With average annual growth of around 7%, Bain predicts the luxury market to be worth about $420bn by 2025.

Spurred on by these figures, last year also saw a resumption of the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity that had taken off before the pandemic. For example, LVMH acquired jewellers Tiffany in January 2021. Three months later, Moncler bought Stone Island brand-owner Sportswear Company. Ralph Lauren sold its Club Monaco brand, and Italian fashion company Aeffe bought up the remaining third of Moschino it didn’t already own. There has also been recent activity on the supply side as luxury goods companies have grappled with supply chain disruption, much like other industries. Towards the end of last year, Chanel boss Bruno Pavlovsky announced his label was investing in the production of raw materials, as wool, cashmere and silk were “becoming more and more difficult for us”.

Transformed by the pandemic

Covid-19 has also brought other changes that may be profound. “The digitalisation forced upon brands as a result of the pandemic is potentially a structural growth driver allowing brands to access new consumers”, says Pictet Asset Management. Those new consumers are to be found in smaller cities situated away from the boutique stores, as well as in emerging markets, such as China with its burgeoning middle class. True, the latter could be affected by the recent slowdown in the Chinese economy and Beijing’s crackdown on conspicuous wealth. As such, Goldman Sachs has reined in its growth forecast for the luxury goods sector for this year, from 13.5% to 9%. But even so, the Chinese market has doubled in size since 2019, and now accounts for just over a fifth of the global market, according to Bain. Emerging market populations also tend to be younger, and millennial and Gen Z customers globally are predicted to make up 70% of the market by 2025.

The industry has already started to cater to the tastes of this cohort. In 2013, former luxury brand designer Ben Branson came up with the idea for Seedlip, a premium non-alcoholic spirit substitute for cocktails that is now majority owned by drinks giant Diageo. The “movement” that led to its creation is “the collision of health, wellness, connectedness, localness, nature – all these different trends and cultural forces colliding”, Branson told Barron’s Penta last summer. By 2024, the premium and ultra-premium section of the drinks market will represent 13% of the total, reckon drinks-industry analysts IWSR. “People want to drink better,” says Branson. “And that means they want to drink better alcohol, and they want to drink better when they’re not drinking alcohol.”

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues are also important to younger consumers. “Luxury goods companies are rushing to shine in ESG terms by ticking all the possible boxes from a reporting standards and an objective setting viewpoint,” says Deutsche Bank in a research note. By taking a firmer grip on their supply chains, brands not only gain an economic advantage in being better able to control their costs, but they can also boast “full product visibility and traceability and to use it to promote sustainable practices as well as differentiate the brand with consumers”. Stella McCartney’s label, which calls itself “vegan”, has created clothing made from Mylo, a sustainable “mushroom leather” made by San Francisco-based company Bolt Threads. Similarly, Hermès reissued its Victoria travel bag from 1997, but with the calf skin replaced with Sylvania, a material that combines mycelium (fungus) with agricultural waste. And Paul Smith and Hugo Boss have produced trainers made with Pinatex, made from the leaves of pineapples. Kering, Balenciaga, Chanel, Salvatore Ferragamo, Tommy Hilfiger, Estée Lauder and L’Oréal are all doing clever things in the lab using cutting-edge technology to create sustainable materials that appeal.

Technology will continue to play a major role in the growth of the luxury goods sector in the coming years. Morgan Stanley predicts that by 2030, the interconnected digital worlds of the metaverse and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) will account for 10% of the luxury goods market, delivering €50bn in revenues and lifting profits by a quarter. The bank points out that a fifth of gamers in virtual world Roblox, “where image is everything”, already dress their avatars daily. Balenciaga has “first-mover advantage here”, while Dolce & Gabbana has previously sold nine NFTs for $5.7m. “This is small in the context of the group’s revenues,” says Morgan Stanley, “but demonstrates the huge potential for virtual and hybrid luxury goods.”

Indeed, last month, toymaker Mattel teamed up with Balmain to sell via auction a set of three of its outfits in digital form specifically designed for Barbie dolls, while Gucci sells a range of “Supergucci” NFTs. And in December, Nike bought British start-up and NFT design studio RTFKT for an undisclosed sum. RTFKT has sold virtual trainers for up to £30,000 in the past. It’s all a far cry from the industry’s not-so-humble beginnings in 19th-century Paris. Fashions come and go, of course, but the long-term growth trajectory of the luxury goods market, driven by tech-minded younger consumers, is assured. And there’s nothing basic about that.

Who's who in luxury goods

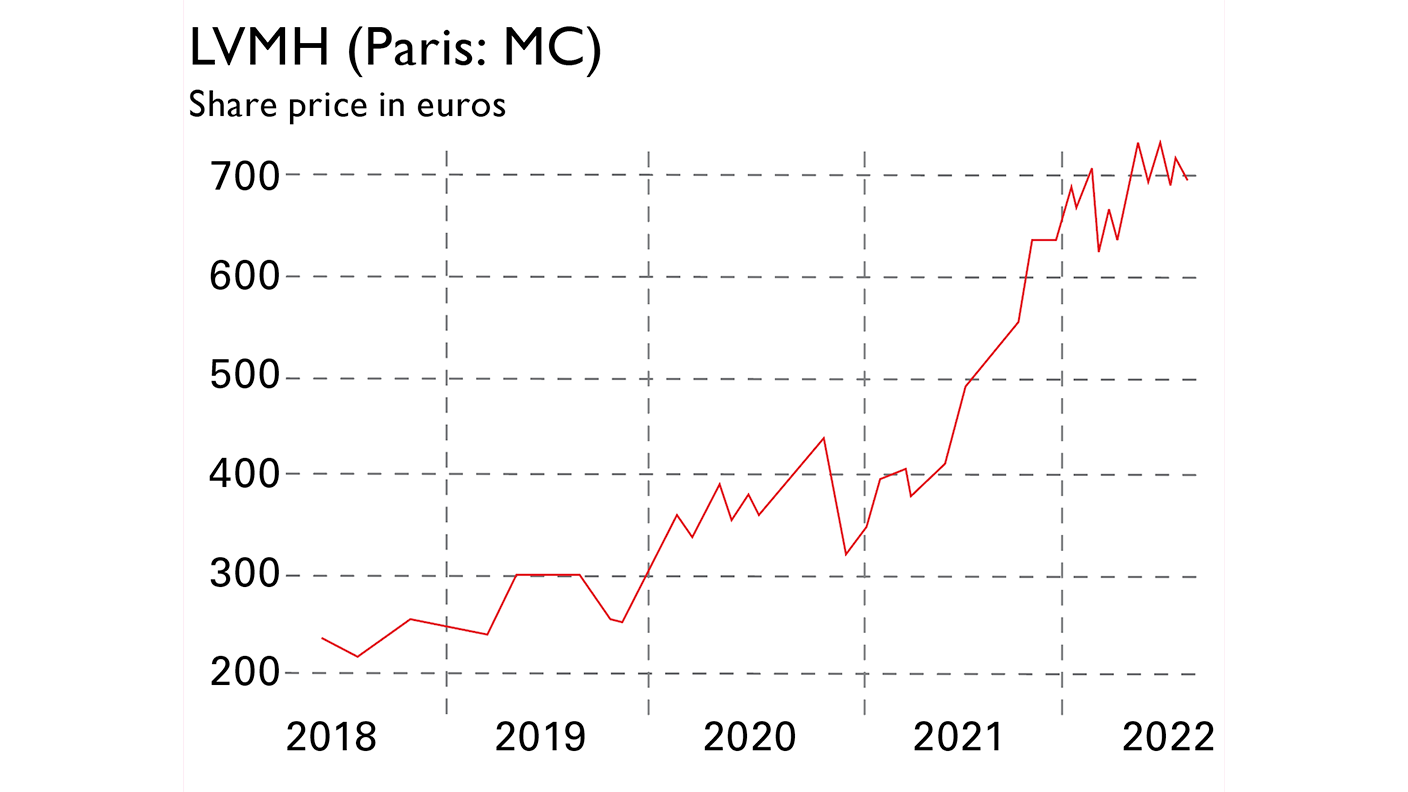

The bigger players dominate luxury-goods sales. Revenue at LVMH (Paris: MC) rose by 44% year-on-year to €64.2bn in 2021, and by 20% compared to 2019, before the pandemic (excluding the impact of its acquisition of Tiffany, sales were up 36%). LVMH has around 75 individual brands (“maisons”) covering a wide range of businesses and is the all-in-one way to invest in the luxury boom through a single stock. Its share-price performance (see chart) is testament to that.

Sales at the smaller Swiss group Richemont (Zürich: CFR) which is also diversified among brands, but more concentrated in watches and jewellery including Cartier – fell from €14.2bn to €13.1bn, but a 30% rise in fourth-quarter sales showed a recovery was underway. The third of the conglomerate-style businesses is Kering (Paris: KER), whose flagship brand is Gucci. It’s roughly the same size as Richemont and saw sales rise 12% in the third quarter. All three are controlled by founders who have made huge fortunes in the luxury sector.

Fashion brand Burberry (LSE: BRBY) expects adjusted operating profit to the end of March to be 35% higher than the £396m reported for 2021. Italy’s Prada (Hong Kong: 1913) recently reported full-year revenues of €3.6bn, up 8% from before Covid-19 dented demand. Other notable listed industry leaders include designer eyewear-maker EssilorLuxottica (Paris: EL), Tommy Hilfiger-owner PVH (NYSE: PVH), Ralph Lauren (NYSE: RL), Hermès (Paris: RMS) and fast-growing skiwear maker Moncler (Milan: MONC).

Meanwhile, premium drinks groups Diageo (LSE: DGE), Pernod Ricard (Paris: RI) and Rémy Cointreau (Paris: RCO) will be toasting the trend for consumers to sip higher-quality tipples. For watch enthusiasts, Rolex and Patek Philippe are both private. However, The Swatch Group (Zürich: UHR) owns the Omega and Tissot brands and offers more focused exposure to that theme that the big conglomerates.

London-based FarFetch (NYSE: FTCH) has benefited from the increase in online sales as well as the growing influence younger consumers are having on the industry. The company has been on a buying spree in the last few years, snapping up streetwear brands New Guards Group and Stadium Goods. FarFetch grew revenues by a blistering 64% in the year to the end of December, to $1.7bn. The shares, however, have failed to keep up, and FarFetch remains loss-making. It’s one for the brave.

If you would rather spread your bets, there, the Amundi S&P Global Luxury UCITS ETF (Euronext: GLUX) follows the S&P Global Luxury Index (note this also includes car marques such as Mercedes-Benz).

Among the actively managed options, there’s the Pictet Premium Brands fund which has taken advantage of recent stockmarket volatility “to add high conviction names with strong pricing power at relatively attractive levels”. The fund has returned an annualised 18.5% over the last three years, and it charges a 1.1% ongoing fee. Alternatively, the GAM Multistock Luxury Brands Equity has returned an annualised 13.6% over the past three years, and charges a 1.25% fee.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both

-

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new look

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new lookThe beauty industry is proving resilient in troubled times, helped by its ability to shape new trends, says Maryam Cockar

-

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?Energy provider SSE is going for growth and looks reasonably valued. Should you invest?

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brands

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brandsConsumer brands no longer impress with their labels. Customers just want what works at a bargain price. That’s a problem for the industry giants, says Jamie Ward