Buy the ammo-makers: how to find value in the AI wars

Big Tech is in a battle for supremacy over artificial intelligence. It’s hard to gauge who will win. Smart investors will back those firms that will profit, whatever the outcome

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Artificial intelligence (AI) is – if you ask any of Silicon Valley’s top CEOs – the biggest opportunity in their company’s history. Few will tell you that it’s also their biggest threat. “For those big players, this is an existential fight for survival,” says Alec Cutler, a portfolio manager at Orbis Investment. “They’re out to eat each other’s lunch.” The big tech companies at the heart of the AI boom face as much disruption to their businesses from this technology as anyone else does. Google Search could become redundant if AI can consistently and reliably start to answer people’s questions. Apple’s position as the world’s premier consumer-products company is under threat because it seems unable to weave AI into its products. Amazon’s shares plummeted when its cloud division grew more slowly than Microsoft’s or Google’s. As Rupert Thompson, chief economist at IBOSS Asset Management, puts it: “The Magnificent Seven… are engaged in an expensive battle among themselves to ensure they end up as one of the big winners rather than a loser from AI”.

Whether this turns out to be a winner-takes-all scenario or something more nuanced, the inescapable truth is that AI’s biggest names trade on huge earnings multiples. Many investors will naturally be put off. “That burning sun in the middle of AI in the US, I’m more convinced than ever, is as much risk as reward,” says Cutler. The costs are huge, the upside is limited, the downside considerably less so. But in his view, the ammunition suppliers – the semiconductor companies and their associated suppliers – will profit, whichever of their customers win (or survive) the AI war.

Cutler doesn’t include Nvidia in that category, despite it having recently become the world’s first ever $4 trillion firm. Broadcom and AMD could both threaten its effective monopoly over AI chips, and all three chipmakers trade at huge multiples. The more Nvidia tries to exercise its pricing power, the more it gives its own customers an incentive to develop alternatives. But all of these businesses are being enabled by the same small and relatively undervalued group of firms.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The AI chipmaker at the heart of it all

Front and centre in this list is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (NYSE: TSM), or TSMC. While Nvidia, Broadcom and AMD are all 'chipmakers', they don’t make their own chips. They design them, but manufacturing is outsourced to a third party. That third party, in almost all instances where AI is concerned, is TSMC, because TSMC is the best in the world at manufacturing the world’s most cutting-edge semiconductors. TSMC has built and nurtured its near-monopoly over decades. The technology involved is extremely complex and capital-intensive; TSMC has already seen off most of its competitors, and the barriers to entry are so high that it has an almost impenetrable moat in the high-end chip-making market.

TSMC makes all of the most advanced chips for Nvidia, Broadcom, AMD and Qualcomm. It also manufactures chips for the “hyperscalers” fighting the AI war – Microsoft, Google and Amazon – and it has made chips for Apple for over a decade. While Broadcom, AMD, or its own customers could take market share from Nvidia, they would all still go through TSMC if they did so. “If Nvidia’s market capitalisation drops, TSMC doesn’t care,” says Cutler.

Nvidia is the most valuable company in the world with a market capitalisation of $4 trillion, and TSMC only recently entered the $1 trillion club. This puts it firmly in mega-cap territory and makes it hard to argue that it is an overlooked gem. But TSMC trades at less than 25 times forward earnings, compared with more than 40 for Nvidia. When you consider the size of TSMC’s moat, and the fact that all of Nvidia’s customers – never mind its competitors – are actively trying to get in on its act, TSMC looks hugely undervalued.

Most commentators put this down to geopolitical risk. Should China decide to annex Taiwan, it could spell bad news for TSMC. But as Cutler points out, Nvidia – and the rest of the US tech infrastructure that relies on its chips – would also be in trouble. The market undervalues TSMC “because Taiwan is in the name”, he says. “But Nvidia is just as leveraged to Taiwan as TSMC is.” In his view, TSMC is “the only company out there that deserves to sell on no-competition margins”.

The data-centre value chain

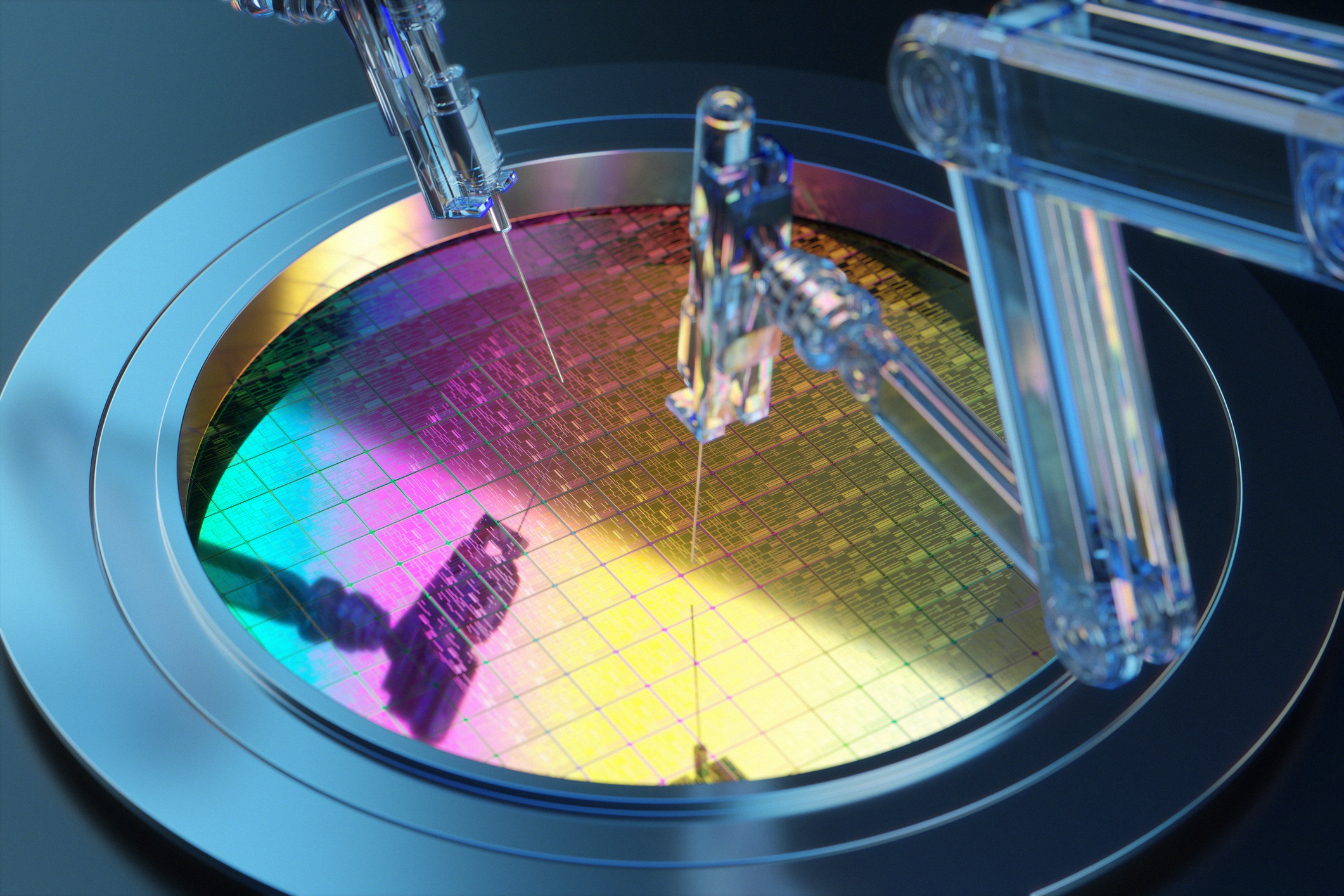

TSMC is just the tip of the iceberg. It has its own suppliers, and its dominance of the semiconductor foundry business relies on specialists with deep expertise. In particular, there is the complex technology underpinning lithography – the printing of patterns onto the silicon wafers that become computer chips. Dutch firm ASML (Nasdaq: ASML) was once the standout name here, and still controls 90% of the market, but it warned in mid-July that it could not guarantee growth next year. Concerns over tariffs and export controls are denting the company’s outlook. Furthermore, it has historically enjoyed a near-monopoly over supply to TSMC, but TSMC revealed in April that its latest manufacturing processes are not reliant on ASML’s extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUVL) tools. ASML’s American depository receipts have fallen 8% in the last month.

But this is a very niche industry, and only two serious competitors can rival ASML’s capabilities in lithography: Canon (Tokyo: 7751) and Nikon (Tokyo: 7731). Both of these dominated the lithography market up until the 2000s, but ASML overtook them in the race to produce the really high-end equipment that leading-edge semiconductor manufacture requires. They now look to be regaining ground: Canon opened its first chipmaking equipment plant in 21 years on 30 July, while last month Nikon started accepting orders for its DSP-100 Digital Lithography System for advanced packaging and panel-level semiconductor manufacturing. ASML trades at around 25 times projected earnings, Nikon at below 20 and Canon at just over 11.

John Scandalios, portfolio manager of the Franklin Small-Mid Cap Growth Fund, also picks out KLA (Nasdaq: KLAC). Trading on a forward price-earnings ratio of 26, KLA isn’t exactly dirt cheap – but it controls more than 50% of the wafer-inspection market and nearly half of the market for metrology equipment, both of which are critical components of the semiconductor production process. “The average person or investor probably isn’t talking much about KLA, and may not even know anything about wafer inspection and process control,” says Scandalios, “but that’s critically important for a lot of these companies.”

Earnings power

The semiconductor industry is highly cyclical in its own right, even in the modern era, where big tech companies seemingly power the global stock market. “It follows its own cycle, often called the silicon cycle,” says Makoto Tsuchiya, economist at Oxford Economics. “It’s quite volatile.” But investors can access the market through a more traditionally defensive industry: infrastructure. AI needs lots of data centres; those data centres require lots of equipment and consume lots of energy.

Pantheon Infrastructure (LSE: PINT) is one investment trust offering exposure to the infrastructure companies behind the AI boom, both through its energy holdings and its digital infrastructure holdings. It subdivides digital infrastructure into fibre, towers and data centres, and its data-centre investments have directly targeted the opportunity in AI. These include CyrusOne and Vantage Data Centres. “It’s effectively providing bricks and mortar” for the infrastructure necessary as AI infrastructure expands, says Richard Sem, partner at Pantheon Infrastructure.

Data centres get through huge amounts of energy: Goldman Sachs estimates the world’s data centres consume around 55GW of power, with this figure increasing 50% by 2027 and 165% by 2030. “Especially in the US, where we have not experienced increasing demand for power in decades, this is very new,” says Pantheon’s Janice Ince. Much of the hype around the AI energy play falls on specialist providers such as Constellation Energy, but it inevitably stretches valuations; Constellation currently trades at around 35 times projected earnings. Most of its capacity is in nuclear, and nuclear power plants take years to build. “Hyperscalers” fighting the AI war need power today.

“Right now, it’s time to power and not cost of power” that matters, says Ince. “The time to nuclear is a decade plus. So while we’ve seen Amazon contract out for nuclear facilities, they’re not getting that power until 2035 at least.” The quickest path to power, she points out, is solar. “You’re looking at at least twice the price it used to be five years ago for a gas turbine,” says Ince. “Plus the timeline to access the larger gas turbines is about five years. So what we’ve been seeing is that the new grid system is co-locating with data centres and putting in solar, putting in storage, maybe putting in small modular gas. That’s been the fastest path forward.”

One of Pantheon’s investments is Calpine – which has solar, geothermal, gas and carbon-capture assets as well as products for battery-energy storage systems. In July it signed a joint agreement with CyrusOne to power a new data centre in Texas. As with the hyperscalers, buying AI energy suppliers can offer better value than buying the core. Balfour Beatty (LSE: BBY), for example, is snaffling energy-infrastructure contracts, including an agreement to deliver the main civil works at the Sizewell C plant in Suffolk.

“The worst-case scenario for Constellation Energy or Dominion Energy or Duke Energy is that they build a nuclear-power plant on stack for AI, and AI falls on its face for a while,” says Cutler. “You just spent $20 billion to build the plant, it takes five to ten years to build, and it’s going to lay dormant for a while.” But if Balfour Beatty is getting paid to build the plants, “I’m [happy] with that”, says Cutler. Balfour Beatty currently trades at around 13 times projected earnings. The value opportunities in AI are continually shifting outwards, further and further from the expensive war being waged at its heart. “We’re constantly evolving where we see the edge of the play, where the expectations are the lowest,” says Cutler.

The Franklin Technology Fund holds Nvidia, Broadcom, TSMC, ASML and KLA. TSMC is also a top-ten holding in Orbis Investments’ Global Balanced Fund.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Dan is a financial journalist who, prior to joining MoneyWeek, spent five years writing for OPTO, an investment magazine focused on growth and technology stocks, ETFs and thematic investing.

Before becoming a writer, Dan spent six years working in talent acquisition in the tech sector, including for credit scoring start-up ClearScore where he first developed an interest in personal finance.

Dan studied Social Anthropology and Management at Sidney Sussex College and the Judge Business School, Cambridge University. Outside finance, he also enjoys travel writing, and has edited two published travel books.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton