How UK banks went from Big Bang to universal failure

The 1986 deregulation shook up the banks, but the all-in-one model that it created is bad for customers and investors. Specialists do a better job – as the real fintech winners are showing, says Bruce Packard

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

It all started with the Big Bang in 1986. That was Margaret Thatcher’s attempt to shake up the cosy relationships in the City of London and build a globally competitive financial services industry of which the country could be proud. The old separation between brokers and jobbers (market makers), and between retail and investment banking, were dismantled and cleared away – without much consideration of whether there were sound reasons for these divisions to exist, like Chesterton’s Fences.

Retail banks such as Lloyds, Barclays and Midland were allowed, if not encouraged, to own stockbroking firms. The likes of de Zoete Wedd, Hill Samuel and Samuel Montagu were bought by UK retail banks. Other brokers such as Phillips & Drew, Warburg’s and Smith New Court were bought by large investment banks from overseas. UK banks expanded into new territories and built empires where the sun never set. Banks attracted a new breed of rocket scientists and physicists to help them price complex derivatives. A new model emerged: “universal banking”, implying a bank could do everything under one roof. London became a centre of global financial competition.

The Big Bang was good for London as a financial centre, but there were two questions no one thought to ask: was it good for customers, and was it good for shareholders? The answer to both questions is an uncontroversial “no”.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Few benefits for customers

Barclays’ fixed-income division may have risen up the corporate-bond underwriting league tables, but it is hard to see how this brought any benefits to a Barclays current-account customer, for example. Even for retail banking products, having a current-account relationship with one bank doesn’t mean a better mortgage deal or cheaper home insurance. It is almost always true that customers do better to look at the best-buy tables than trust their bank to cross-sell to them. This is especially true of mortgages, where high house prices mean a large mortgage over 30 years is very sensitive to the interest rate offered, and hence customers would be mad not to go to a mortgage broker to find the best deals on offer. The same logic applies to credit-card customers, driven by eye-catching balance transfer rates. So using current accounts to cross-sell additional banking products has proved more difficult than universal bank management would like to admit.

It is even harder to see how a customer of what was once Midland and is now part of HSBC benefits from the parent company’s high market share in Hong Kong, let alone the ill-advised expansion into Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, or risky US subprime mortgages. It is patently ridiculous to claim that HBOS, the UK’s biggest mortgage lender, was somehow helping local borrowers in Halifax by also lending money to fund the buy-out of M Resort Spa Casino in Las Vegas in the run-up to the global financial crisis in 2007-2009. Indeed, HBOS’s management were securitising their high-quality UK mortgages and selling them in financial markets, and replacing these assets with collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) sold to them by US investment banks, which contained packaged up lower-quality US subprime mortgages.

No economies of scale

Aside from customers, the universal banking model has not been kind to shareholders either. The UK banks have underperformed the FTSE All Share index since 2002. Yes, even before the financial crisis banks were unloved by fund managers, who worried about overleveraged balance sheets, and how sustainable returns on equity would turn out to be. As it happened, the fund managers were right to be wary.

As the pull of size and consolidation worked on UK banks like gravity, this was justified in the name of efficiency. The trouble is that there is very little evidence that big banks are more efficient. Instead, they became in danger of collapsing under their own weight, like financial black holes. The cost/income ratios for large UK banks such as Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds and NatWest were all above the 60% level in the 2020 financial year – not much improvement from cost/income ratios seen ten, 20 or even 30 years ago. The smaller UK mortgage banks such as Northern Rock (before it failed) operated a more efficient model, with a cost/income ratio close to 30%.

My own experience of banking efficiency as an employee supports this. Over the years I have worked at both large banks (Credit Suisse, Societe Generale) and smaller brokers (none of which have survived to the present day.) Arriving at any small broker on my first day of work, my IT systems were set up, my Financial Services Authority registration had been transferred over and my new colleagues were pleased to see me. At large banks the first day tended to be shambolic. Most conversations with HR and IT started with the sentence: “Oh, hello! We didn’t know you were starting today”.

That’s because bringing all the banking activities under one roof created more complexity than any efficiency savings. Banks still needed to spend lots of money on technology systems. And any savings from streamlining the back office were lost, because they needed to employ an army of legal and compliance staff to manage conflicts of interest, for instance building “Chinese walls” to keep employees with inside information separate from market-facing roles and prevent the bank being fined by the regulator. The huge increases in computing processing power and decline in the cost of computer hardware hasn’t benefited shareholders in banks at all. By December 2014, Antony Jenkins, the then-chief executive of Barclays, was admitting that the universal banking business model was dead. Diversifing by business, customer and geography hadn’t worked.

Banks have many challenges

In recent years, low interest rates have made life even harder for banks. Most of the time, banks make a margin on their retail deposit funding, because their average interest costs are below central bank rates. But when base rates drop below 1%, margins shrink because the banks can’t charge customers enough for looking after their savings (notwithstanding the efforts of some European banks to levy negative rates on retail deposits). As interest rates rise, analysts expect banks to increase revenue. Still, while margins are set to improve, technology spending is likely to rise even faster and bad debts are hard to predict.

Setting aside the barrage of regulatory fines, the other reason that banks have struggled to generate the return on equity (ROE) that the market wants (10%) is that the regulator has demanded that they fund their balance sheets with less debt and more equity. Larger banks that are judged “systemically important” have to fund with even more equity, because of the serious consequences of failure. In very simple terms, that even bankers can understand, if the “R” of ROE stays the same but the denominator “E” increases, then it is a mathematical inevitability that ROE will fall.

A further problem is that banks tend to reward their loyal customers with worse deals than the new customers they are trying to tempt away from other banks. In the short term, this strategy works. Customers have better things to do than check they’re still getting a good deal every couple of months. But over time, the strategy is bad news for shareholders. It’s terrible for banks’ brands to use inertia from loyal customers to generate high returns. Thus the last few years have seen disruptive new entrants, such as Atom, Monzo, Starling and Funding Circle.

In theory, these financial technology (fintech) firms can offer more competitive services because they don’t have legacy IT system costs or a branch network. That said, given that the disrupters tend to be loss-making, it could just be that their services are being funded by deep-pocketed venture capitalists.

Last year the UK saw $11bn of investment into fintech. There were 713 deals, with Revolut, Monzo, and Starling in the top five amounts raised. Zopa, the peer-to-peer lender founded almost 20 years ago, still managed to raise $220m from SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2. The UK fintech sector seems particularly good at attracting capital, because that $11bn is more than double the next largest in Europe: Germany ($4.4bn), followed by France ($2.3bn) and Sweden ($1.7bn). Overall, $24.3bn was invested across the continent in 2021, with the UK representing nearly half (45%).

Most disrupters aren’t disrupting

That sounds impressive, yet the pandemic has not been the boon for fintech that it has been for tech firms, as Marc Rubinstein points on Net Interest, his financial sector blog. Monzo’s fund raise in May 2020 was at a 40% discount to its previous funding round. German digital bank N26, funded by Peter Thiel, pulled out of the UK after finding the competition too strong.

Meanwhile, branch-based challenger bank Metro Bank has fallen 95% since its initial public offering (IPO), while peer-to-peer lender Funding Circle is down 75% since its IPO at the end of 2018. These have not been anyone’s idea of a successful investment.The problem is that UK banks’ core business of taking customer deposits and lending out money is highly competitive. Thus the fintech winners are not the ones trying to re-invent universal banks. Revolut and Wise (formerly TransferWise) show that fintech isn’t just about technology, it’s also about finding the areas of greatest risk-adjusted return. They have focused on cross-border payments, attacking the huge difference between the currency rates available to large corporate clients in wholesale markets and the price that retail banking customers pay.

Ten years ago there was a complaint to the Office of Fair Trading by consumer groups because banks were charging 3% on foreign currency transactions. Some debit cards also added a further fee of £1.50 per transaction, while using a bank card to withdraw cash abroad could cost up to £4.50 a time. At the time a spokesman for the British Bankers’ Association (BBA) blamed the high fees on foreign payment systems, saying “transaction costs abroad are driven by the costs of overseas payment systems, often in countries where free banking does not exist”.

Of course, this was nonsense. And hence both Revolut and Wise were founded by eastern Europeans who were appalled at the price gouging from banks when they wanted to send money home.

Wise and Revolut: the two winners

Wise was originally a way to send money to bank accounts overseas (see below). It unbundled a specific financial product and offered better value than the competition, with no cross-subsidisation.

Revolut began as a pre-paid card and an app for spending money abroad. It planned to levy a small fee every time a customer used the card, but realised that there wasn’t enough money in this to support the cost and started charging subscriptions. It is remarkable that an app can charge customers up to £13 a month, while UK retail banks with higher-cost branches and legacy systems struggle to convince customers to pay anything. Rather than lower costs, Revolut is able to make money by charging customers to access services they value, such as crypto trading, which has done well over the pandemic. That said, Revolut’s subscriptions made it £222m of revenue in 2020, but direct costs and administration expenses meant that the business made a loss of £207m the same year.

Wise and Revolut attracted millions of customers, despite not having a banking licence. They had an e-money payments institution licence, which means that they weren’t able to lend out money to borrowers and take credit risk. Instead, they have to keep customer funds in cash or other low-risk alternatives. (Revolut was granted an EU banking licence last year.)

So the great irony of fintech is that technology has not meant bigger, more efficient banks. Nor has it allowed new entrants using technology to disrupt saving and lending. The real success story is built on the fact that wholesale customers who deal in large size receive a better price than individuals. That’s true in any industry and financial services is no different. That was the original reason for brokers (who bought and sold on behalf of retail clients) and jobbers (who made a market and dealt wholesale). Wise and Revolut have used technology to reduce the size of the retail versus wholesale price difference. That outcome is light years away from anything foreseen at Big Bang.

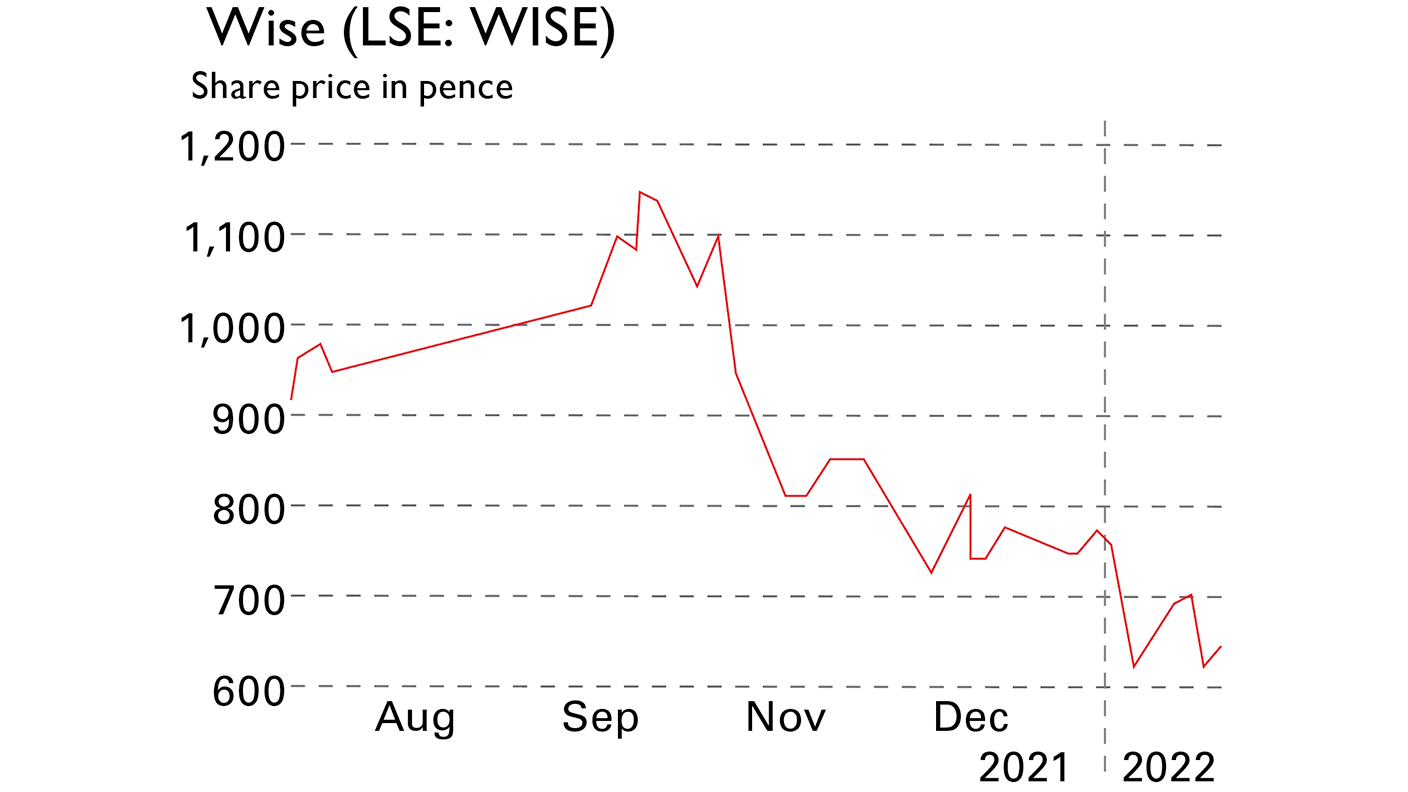

Is Wise worth 90 times earnings?

Wise (LSE: WISE), which has a March year end, put out a third-quarter trading update in mid-January. It’s enjoying strong growth, transferring over £20bn in the three months to December, up by 38% from a year ago. So far this strong transaction growth has meant reducing costs, the benefit of which it shares with customers by driving down fees, while generating cash for reinvestment.

The firm says that over the last year it dropped prices across 50 currencies and fees are now 0.60% of transaction value on average, nine basis points lower than a year ago. It was profitable in the first half of the year, to September 2021, making £19m, and analysts are forecasting profits to reach £150m in the 2024 financial year, according to data from SharePad.

Analysts covering Wise are forecasting around 24% revenue growth in 2023 and 2024, and the total addressable market for cross-border transactions is huge. There were around £2trn of global cross-border payments made by individual consumers in 2020. Around two-thirds of that is done by banks – Wise estimates that it has a market share of around 2.5%. That £2trn pool is also growing.

Like many fast-growing tech stocks, the shares look expensive. The forecast price/earnings (p/e) ratio is 90 and price/sales (p/s) ratio is 15, according to SharePad.

This approach to growing fast and sharing efficiencies with users is similar to Amazon’s. Even after 25 years of growth, the “Everything Store” now has revenue of half a trillion dollars, but shows no signs of going ex-growth. It trades on a forecast p/e of 70. In his 2005 letter to shareholders, Jeff Bezos described Amazon’s strategy in this way: “Our judgment is that relentlessly returning efficiency improvements and scale economies to customers in the form of lower prices creates a virtuous cycle that leads over the long-term to a much larger dollar amount of free cash flow, and thereby to a much more valuable Amazon”.

Wise, like Amazon, intends to expand its product offering. It recently launched a service called “Assets” for UK customers. They can now transfer balances to an index fund, while still being able to spend or transfer money overseas as though the balance were still held in cash.

There are risks to Wise. One concern is the co-founder, Taavet Hinrikus, selling 11 million shares last year, and entering a loan agreement with Goldman Sachs where up to 49.6 million shares would be pledged as security. There’s also a dual share structure common to many tech stocks. The founders hold B shares that have nine times more votes than the A shares. That lets them keep control even if they decide to cash out their A shares.

I think the bull case is relatively easy to make, but the high valuation multiples mean that if the company disappoints, then it’s likely to be punished severely. For every Amazon-style investment, there are plenty of Groupons and Pelotons that don’t receive much attention – once hyped stocks that failed to deliver.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Bruce is a self-invested, low-frequency, buy-and-hold investor focused on quality. A former equity analyst, specialising in UK banks, Bruce now writes for MoneyWeek and Sharepad. He also does his own investing, and enjoy beach volleyball in my spare time. Bruce co-hosts the Investors' Roundtable Podcast with Roland Head, Mark Simpson and Maynard Paton.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton