The three key risks for investors in China, and how to tackle them

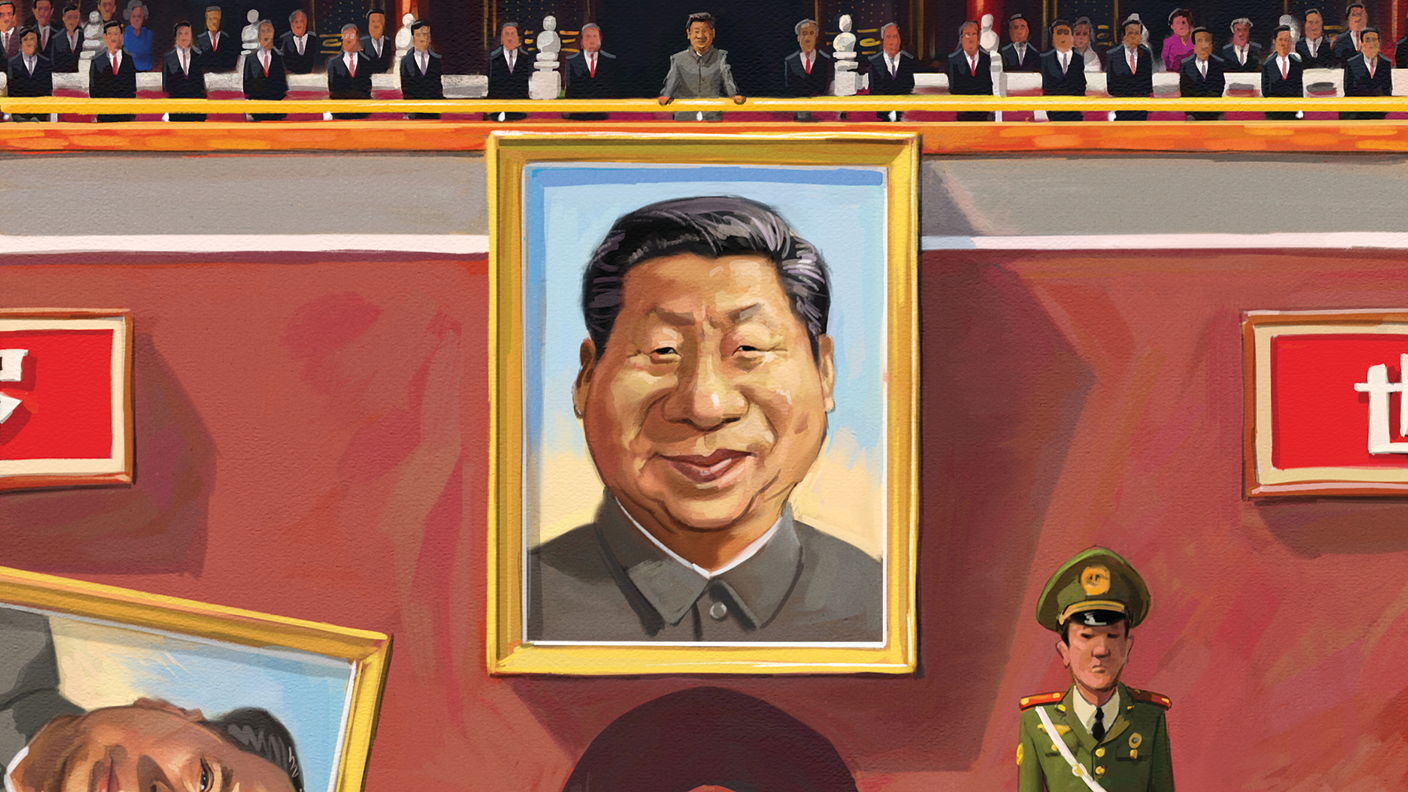

Xi Jinping’s vision for the future of China is very different to the past. Stricter social control and the slow struggle to tackle problems in the economy may not be good news for markets, says Cris Sholto Heaton.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There was just one official outcome from the Sixth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party earlier this month. More than 300 top members of the party met for the last time before next year’s national congress to approve a resolution on the party’s history and achievements – essentially a document that talks at great length about how hard the party has worked, how much it has done for the people and how it will keep up its efforts in future.

That may seem a scant return for a four-day closed-door meeting, but it has symbolic significance. This is the third time that a Chinese leader has issued a resolution on the party’s history: Mao Zedong did so in 1945 and Deng Xiaoping in 1981. By doing the same, Xi Jinping elevates himself alongside them in the pantheon of leaders, ahead of his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Xi is mentioned 17 times in the resolution, compared to seven for Mao, five for Deng and one passing mention each for Jiang and Hu.

The signal is clear. Not only will Xi continue as leader next year (there was no real doubt about this), but he represents a new era for the country, shaped solely according to his vision. The future is Xi’s China, for better or worse. The problem is that the trends increasingly say that it will be for worse.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Running out of time for reforms

There are three distinct – though closely connected – reasons to be concerned about the outlook for China. The first is the structural weaknesses of the economy. Economists and investors have been talking for many years about the need to rebalance from investment towards consumption. The problem is that this isn’t happening. Private consumption only accounts for around 39% of GDP, up from 35% a decade ago.

If China was investing productively, this would be less of an issue – but it’s clearly not. You can see this in a number of areas, but one of the most important and high-profile areas is residential real estate. This accounts for around 29% of GDP when you factor in everything connected to it. There is little question that there is a huge real-estate bubble and a lot of very indebted developers building properties that are often purchased for investment rather than use (about 20% of Chinese residential real estate is reportedly empty).

The Chinese government is very much aware of this and wants to curb the excesses in the sector – hence the public crackdown on real-estate lending earlier this year, which has brought a number of developers such as Evergrande to the brink of failure. The difficulty is that squashing a bubble like this isn’t simple – the economic linkages are complex and actions can have far-reaching consequences.

Most obviously, the collapse of developers affects anybody who has lent to them, suppliers who are waiting to be paid and buyers who have paid for off-plan properties that may not be completed. However, bursting a wider bubble in the sector will affect the wealth of people who have bought property, with effects on consumer confidence. Less demand for new land from developers will affect local governments, who in China need to cover much of their spending and investment from land sales rather than taxes or issuing bonds. The government is not blind to this. For example, last month it announced a pilot programme under which around ten cities will levy property taxes, with the idea of introducing it nationwide after 2025. This could put local-government finances on a sounder footing, making them less dependent on the property and land price bubble, and generally reducing the outsize role that the sector plays in the wider economy.

But many changes are not easy, quick, certain or controllable. The government’s efforts to squeeze the sector may not go far enough, in which case unproductive real-estate investment will continue to be a long-term faultline in the economy, even if it helps to support growth for now. Or they may bring everything crashing down fast. In the last two months, property prices have fallen for the first time since 2015, which some analysts already fear could be the start of a slump that will spread to the wider economy.

Real estate is just one problem, albeit a very large one. There are plenty of other poor-quality investment by state-owned companies or local governments. The economy would be a lot sounder if this spending was instead flowing to individuals and households as income. None of this is a new idea – and Xi’s flagship policy of common prosperity aspires to spread wealth more equally. However, the details of how this will happen are non-existent and China’s window for dealing with these profound problems is shrinking because its demographics are becoming increasingly unhelpful. A decade ago, the dependency ratio – the ratio of old and young to working age people – was 34%. Now it is 42% and set to climb faster.

This will naturally bring down the long-term sustainable growth rate. Transitioning from a model driven by lower-quality investment towards a more balanced one isn’t painless in the most favourable conditions, but it will feel even harder when the economy is growing more slowly. So the temptation to prop up growth through yet another round of investment is likely to become even greater if GDP drops to 3% (which might be the sustainable rate) instead of 6% in the years ahead. In short, the longer that China puts off real change, the harder it may be.

The heavy hand of the state

The second concern is the heavy hand of the state in all areas of the economy and society. Xi and his key advisers clearly believe that China has taken the wrong path. There are aspects to their vision that could be positive, at least in principle. For example, it is likely that Xi’s wide-reaching anti-corruption campaign reflects genuine personal disgust with the level of corruption in modern China rather than a simple pretext to purge political rivals. That’s not to say the campaign is well-conducted: it creates a climate of fear, it has served to crush opposition to him, and it does nothing to bring about the transparent and predictable rule of law that China badly needs. But the ambition of tackling corruption is understandable.

Similarly, the crackdown on high-flying tech companies such as Alibaba that began last year is reasonable in many ways. These firms had grown very large, very powerful and often quite monopolistic, due to their success in skirting ineffective regulation. Taking action against them might be beneficial for the wider economy even if it hurts shareholders in those individual firms. The problem is the suddenness, the lack of clarity in terms of the government’s long-term intentions and the abrupt reminder that private property rights are ultimately very limited.

China never gave up on the idea of a large role in the economy for the state, but it is unambiguous that Xi’s administration sees the state as far more dominant than under his recent predecessors . Whenever there is a situation in which the government feels that private businesses are not serving its social goals, it will step in. Sometimes this is survivable. After Alibaba’s time in the spotlight, Tencent took a beating over concerns that children are playing computer games too much: it and its rivals must now restrict access for children to just three hours a week at specific times. That’s unwelcome for games companies, but not a fatal blow.

However, when the government decided to outlaw for-profit private schools for children earlier this summer, it destroyed a thriving private educational sector. US-listed shares in New Oriental Education & Technology, the largest and best-known provider, began 2021 at $17 and now trade at around $2. This decision was directed at the wide use of after-school classes and private tutoring by ambitious parents, which the government says puts too much pressure on children. The government also apparently hopes removing the social pressure to pay for expensive private tuition will raise the birth rate and eventually alleviate the country’s demographic crunch (the expense of raising children is often cited as a reason why many people remain reluctant to have large families even though the one-child policy has been abandoned). There is certainly a good case that children are under too much pressure and so the aim may be laudable. But the fact that businesses that have been built up over decades can be wiped out so quickly shows how easy it is to end up on the wrong side of the government’s new priorities.

However, the problem goes deeper than control of the economy. Under Xi, the state has cracked down ever more heavily on freedom of speech and discussion of any issues that could be considered sensitive. In the mid 2000s, what could be freely debated or reported had steadily expanded in China. The climate became somewhat more restrictive around the time of the Beijing Olympics and did not fully open up again – but in recent years the shift towards repression has become far more severe. Journalists are much more restricted in what they can report and censorship on social media has become stricter. Newspapers are now full of fawning articles about Xi’s virtues and vision.

The ability to debate policies is constrained even in academia, while high-profile critics who might previously have enjoyed some element of protection because of their status and connections have been silenced. Real-estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang, who had been a blunt critic of Xi and the party, was last year jailed for 18 years on allegations of corruption, in what was widely seen as a warning to others.

Obviously, to anybody who values freedom of speech, this is appalling. However, it’s also bad for China regardless of the human-rights issue. Shutting down the ability to report, discuss and debate increases the risk of making mistakes. Policies are not publicly scrutinised, while the information reaching top decision makers become more one-sided.

The third concern is international relations...

To read the whole of this article, subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine

Subscribers can see the whole article in the digital edition available here

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?