House prices in the UK are still surging – here’s why it’ll probably continue

The latest UK house price data shows no letup in the country’s booming property market, with the biggest yearly rise since 2014. And there’s no end in sight yet, says John Stepek. Here’s why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

UK house prices (and those across the globe) appear to have done rather well during lockdown. Now that the economy is opening back up, can that continue? Unfortunately for anyone who wants to buy an affordable property in the near future, the answer appears to be “yes”.

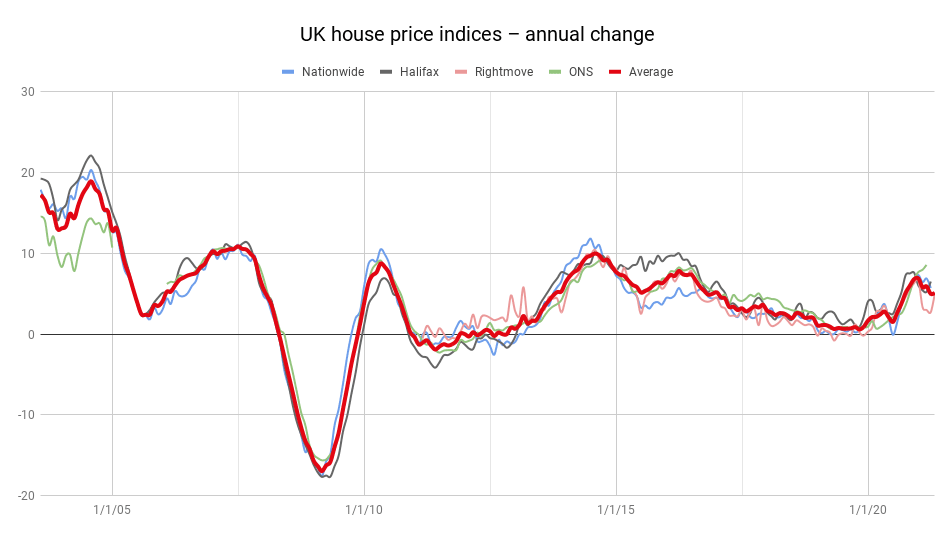

There are an awful lot of house price indices in the UK, which is one reflection of how obsessed we are with them. The best-known ones are probably the Nationwide and Halifax indices. They’ve both been running for a long time and they both cover roughly the same stage of the process – they’re both based on data from approved mortgages. In other words, deals could still fall through but you’re far enough into the process that the price is pretty accurate, rather than aspirational.

Rightmove asking price data is also quoted widely. Clearly, this is based on listings for properties and therefore reflects seller aspirations rather than actual prices. There are lots of other indices too.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

But the official one comes from the Office for National Statistics. This one uses data from the Land Registry, so it comes from actual sales. The latest reading from February shows that house prices rose at an annual rate of 8.6% in February. That was the highest seen since October 2014, and considerably above the rate of inflation.

The death of the commute and the rise of the towns

We already know some of the factors driving this. As the ONS points out, “the pandemic may have caused house buyers to reassess their housing preferences.” Detached home prices rose by 9.1%, compared to 6.7% for flats – people want bigger spaces.

There is also a “death of the daily commute” trend still in effect here. This takes a number of forms. The obvious one is people moving out of big cities (mostly London) to take up more space in bucolic provincial towns (I note that The Telegraph has just put out a listicle of “21 fashionable ‘it’ towns that you can still afford to move to”).

Apparently the gap between the valuation of a central London property and a luxury country property is at its narrowest since 2010 (it’ll cost you 2.4 times as much to live in central London as in a country mansion, compared to three times in 2014).

Also note that on average, London prices rose by “just” 4.6%, by far the lowest of all English regions (the northwest of England saw prices rise by nearly 12%).

A slightly less obvious one is companies deciding to relocate outside of London (because the property – and staffing – is expensive) for premises in less expensive cities (Birmingham has been a big beneficiary – Goldman Sachs has decided to open a global software development site there, rather than Amsterdam or Paris, for example).

Much of this was already happening, but it’s only likely to be given an added impetus by the fact that the daily commute is no longer such an issue. That’s likely to last – it’s not clear how much commuting has changed yet (some companies are very keen to get everyone back in the office – others have already embraced the shift) but the average has almost certainly moved permanently.

Another obvious factor in the UK is the stamp-duty holiday. This is clearly bringing some demand forward and the extension announced in the spring Budget has kept the sugar rush going.

It’s ultimately the same story as usual – cheap and cheaper money

However, some of it also just comes down to the same old point we’re always making: there’s a lot of money sloshing about it, and increasingly it’s making its way into property.

Here’s an interesting thing, for example: everyone has been focusing on the government’s latest scheme to prop up the market – taxpayer-backed 95% mortgages. But as property commentator Neal Hudson of BuiltPlace.com points out, Nationwide has just released its own “help out first-time buyers” scheme.

Nationwide – which, it’s worth noting, is typically a pretty cautious/responsible lender – is now offering first-time buyers the chance to borrow up to 5.5 times salary as long as they have a 10% deposit, and are taking out a five or ten-year fixed-rate mortgage. There will be £1bn-worth of the loans available.

One key aspect here is that Nationwide has clearly squared this with the regulatory regime. So that probably means that other banks will follow suit.

If we continue to see lending on mortgages becoming more easily available, then it’s very hard to see how house prices might fall. As always, the key indicator to watch here is credit availability and so far, that’s not getting tighter.

In the longer run, the ideal is that inflation starts to accelerate properly, so that you get wages rising faster than house prices. So house prices go down in “real” terms (ie after inflation). That means affordability improves.

It also means that in reality, the value of the house has gone down. However, it goes down in a less painful manner than if the actual price fell in nominal terms. Why? The key benefit is that you don’t get a disruptive correction.

The problem with house price crashes (and property crashes in general) is that banks lend lots of money to people to buy property. If prices crash, it means the collateral underpinning the loans is no longer as secure. That in turn makes banks more wary of lending money. So a house price crash is a deflationary event. In turn, that’s one reason why governments aren’t going to want one to happen.

What does this mean if you want to buy a house? Well, I’ve explained before that timing the market if you’re looking for a house to live in, is a self-destructive idea. Here’s what really matters. So don’t worry about that.

As I’ve said before, if you’re looking to rent or you’re already renting in London or big cities, that’s probably where your best value bets are. Don’t be shy to negotiate – renters don’t often have the upper hand so take advantage.

And if you’re thinking about investing... well, that’s a tough one. But for more on this, you should listen to Merryn’s latest podcast with Peter Spiller of Capital Gearing investment trust. They discuss financial repression and whether or not a more inflationary environment would mean that houses might be a good investment. You can listen to it here.

Until tomorrow,

John Stepek

Executive editor, MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.