The US is in one of the greatest bubbles in financial history

Jeremy Grantham, who has a history of getting big calls right, fears slumps in several wildly overpriced markets (including UK property). He tells Merryn Somerset Webb what investors should do now

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“Today, it is clear to me that this is the most dangerous package of overpriced assets we have ever seen in the US. [Bond guru] Jim Grant would say that we have the most overpriced fixed-income market in the history of man.

“That, combined with an equity market that can easily lose $5trn or $10trn, depending on the magnitude of the break, is a contender for the highest-priced market in American history.” The result could be “a writedown in perceived wealth that would have no precedent”.

So wrote Jeremy Grantham, co-founder and chief investment strategist of Boston-based asset management group Grantham, Mayo, Van Otterloo (GMO), a few months ago. It’s a dramatic prediction from a man with a history of getting things right. For instance, he rightly dismissed the 2003-2007 stockmarket rally as “the greatest sucker rally in history”, warned that the housing bubble of the mid-2000s would burst, and turned positive on stocks in March 2009.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So when we talk on the MoneyWeek podcast (listen to the whole thing here) this great bubble is one of the first things I ask him about. Just how big is it? And – given that the markets have looked expensive for a long time already – how might it end?

A slow, 12-year build-up

It’s big. This has been one of the longest economic upswings we have ever seen. Take out the Covid-19 “blip” (a quick down and up) and “the long, slow build-up had gone on for 12 years”. At the end of a long upswing such as this, “you’re likely to have very substantial profit margins, and if history repeats itself, investors are likely to consider that the high profit margins will last forever”.

That’s the first part of making a bubble: “Very strong economics extrapolated into the indefinite future.” The second part is easy money, which we also obviously have in spades.

Alan Greenspan, former chair of the US Federal Reserve, may have introduced America’s “aggressively pro-asset formula” of cheap money and moral hazard back in the 1990s – but today, rates are the lowest in history and we have just seen the biggest increase in the money supply ever too (a 25% year-on-year rise in the US).

Things have been pretty stimulative outside the US but in most places this just means being at the “top end of their historical range”. Not so in the US, which has “broken way out” in terms of both government and Federal Reserve stimulus. It’s the same with equity markets. Most are at “merely normally high prices”, but the US is a candidate for the highest-priced market in its history.

Big Tech’s extraordinary performance

What makes this worse than a bog-standard bubble? Capitalism, says Grantham, “particularly in the US [which] is a little fat and happy”. The US Department of Justice has allowed industry to become far more monopolistic and concentrated than ever before. But at the same time, companies are less aggressive than they once were. Between the 1960s and the 1990s market share was all that mattered. Now many of the big firms focus on profit margins, using cash flow to do buybacks, for example (something executives love anyway as it works so well with their stock options and is “very low in career risk”).

Look at profit margins in the US and the rest of the world and again you see the difference. In the rest of the world, profit margins have stayed reasonably high but the US has “crashed up to record highs” with a “fairly astonishing 80% gain over the rest of the world in profits”. Even more astonishing however is the fact that something like 85% of this is accounted for by the huge tech companies. “The performance of [Big Tech] has been extraordinary – there’s been literally nothing like it in history, anywhere.”

Take Apple, the company with the biggest market value in the world. Last quarter it announced that sales had risen by 50% in the past 12 months. “Give me a break, this is the largest company in the world,” says Grantham. Traditionally, a brilliant year for a company of this size would mean growth of, say, 5%-6%. There is no precedent for this kind of expansion. “One has to admit these are exceptional companies.”

The secret to America’s success

So here’s an interesting question: why is it that the US has such a dominant share of these great new interesting firms? The answer to that one, says Grantham, is the venture-capital industry. American exceptionalism is not what it was, but one place where it is still very much on the go is here.

The US has two-thirds of the world’s great research universities, something venture capital really feeds off. It also has the right attitude to risk. Americans “forgive failure, they go back and try again, and they throw money at new ideas, and they’ll do 20 new deals, where the careful Germans will do one.

“And so, they have many more failures, but when the smoke clears out of the wreckage of the internet, the Amazons, and for a while the AOLs, tend to be American, and they own these great new enterprises. So, I look at [Big Tech] and I say: where did they come from? And the answer is, they all jumped out of the venture capital industry in the last few decades.”

Still, none of this really justifies the valuations, particularly since the tide may be beginning to turn: note the way in which China has been “bashing its new, special, powerful monopolistic entries”. So what will be the thing that brings this bubble down?

Where is the pin?

There is no point in looking for a pin, says Grantham. “No one can tell you what the pin was in 1929. We’re not even certain in 2000. It’s more like air leaking out of a balloon. You get to a point of maximum confidence, of maximum leverage, maximum debt, and then the air begins to leak… because tomorrow is a little less optimistic than yesterday.”

There are, however, warning signs. “Before the great bubbles ended in 1929, 1972 and in 2000, in the US, the three great events of the 20th century, there was a very strange period in which, on the upside, the super-risky, super-speculative stocks started to underperform.”

Think of it in terms of “confidence termites”. They start with the speculative stuff and gradually reach the rest of the market. This time round we are tracking that path “quite nicely”. When Grantham and I spoke (four weeks ago now), the Spac (special purpose acquisition company) index, bitcoin and Tesla were all substantially off their highs. The Biden stimulus and the good vaccine news have pushed this bubble out longer than Grantham ever expected – as has the huge breadth of market participation. In 2000 it also seemed as though everyone was in the market.

Watch out for the “confidence termites”

“My favourite story, which is completely accurate, was that [in] the local greasy spoon... in the financial district of Boston [there were eight] television sets [and] all but one of them would be showing talking heads from MSNBC and CNN and [the eighth] would be showing replays of the Patriots football team. And a year earlier... eight out of eight were showing the Red Sox.”

You see something similar today: endless talk about Tesla sales and huge numbers of new traders in the market, all too many of them using options. Grantham reckons the termites will have made it to the rest of the market by the end of the year.

Where to look now

Oh dear. Is there anywhere safe for investors, I ask? Back in 2000 there were plenty of cheap things around – houses weren’t horribly overpriced, and neither was the bond market; and value stocks were actually cheap. Grantham agrees there is much to worry about if you are looking at the kind of things that get the confidence termites going: the coming of the bezzle (the fraud cases that appear at the end of bubbles); more evidence that this bout of inflation is not transitory; and, in the US in particular, a worsening of the pandemic.

On the plus side there are some relatively safe havens. One place you really should have some money is in US venture capital. “It’s far and away the most virile part of American capitalism. It has all the ideas. All the best and brightest now come into venture capital, all starting their new firms, as they should.”

His own Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment has moved its assets to 70% venture capital, with much of that focused on the wall of money heading for decarbonisation.

There will be huge amounts of money “trying to get into the new ideas... and they will really prosper.” And the established green companies will also be beneficiaries. GMO has had a climate-change fund for the last several years, for example. “It’s doing extremely well. And it will get hurt in the burst, but it’s a global fund. It will go down less. It will come back quicker. It will run further.“

Beyond that, note that overall the equity market is not as overdone as bonds and real estate (the UK housing market, he says, is a “humdinger” – see below), so if you stay out of the US, choose carefully and emphasise emerging markets.

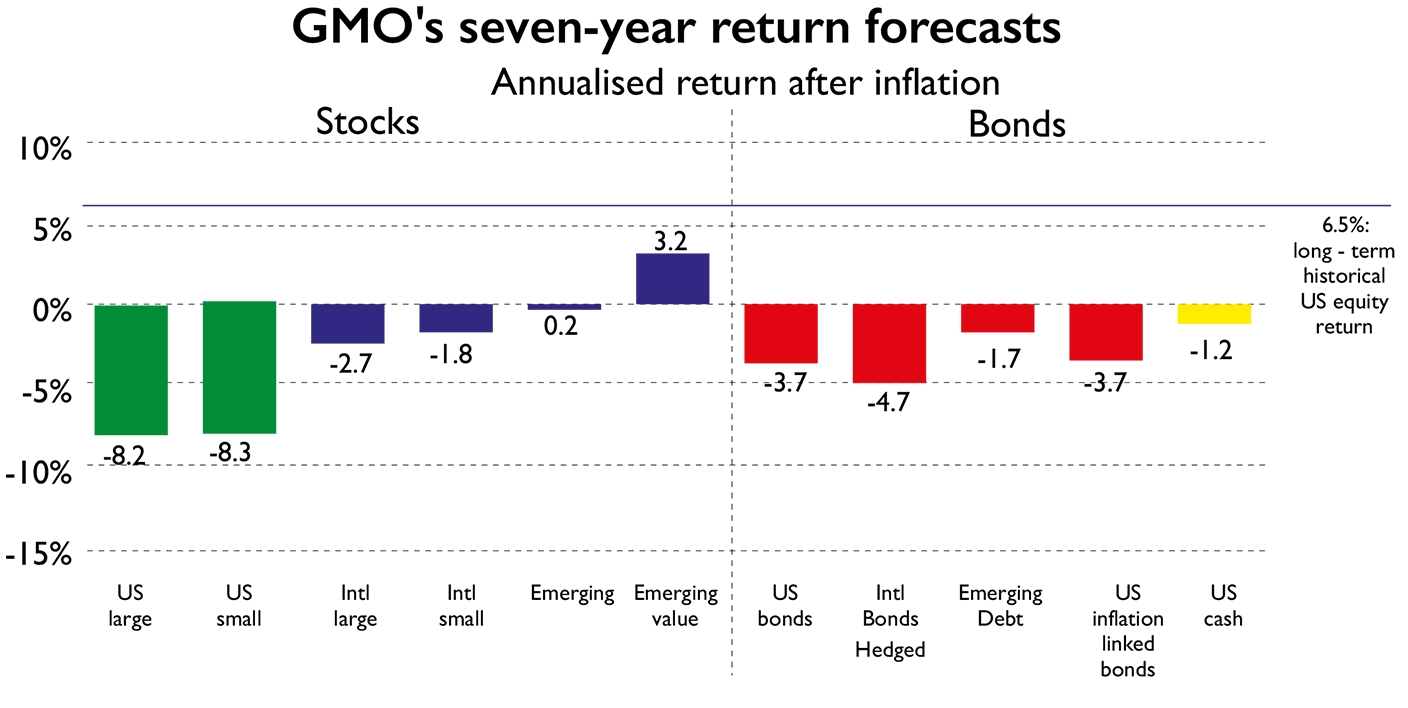

When the US market collapses all markets will temporarily, at least, come down in sympathy (this is a reason to hold some cash so you can pick up the bargains by the way). However, “you will make a respectable return. Not as much as you would like, but a respectable return” over ten or 20 years. GMO’s current forecasts of annualised seven-year returns for various asset classes (see chart above) suggest that the best value is in this area – high starting valuations imply poor long-term returns. (For context, US stocks have returned an annual 6.5% after inflation over the very long term.)

Grantham would also suggest steering your portfolio towards value stocks, which are “about as cheap as it gets… compared to the other half of the market”. Perhaps buy “the cheaper low-growth stocks in emerging [markets] and carefully-selected other developed countries” (not the US). But whatever you do, do not let yourself believe that everything is fine. It isn’t. This “is a really splendid speculation”, says Grantham, “and of course it will end badly”.

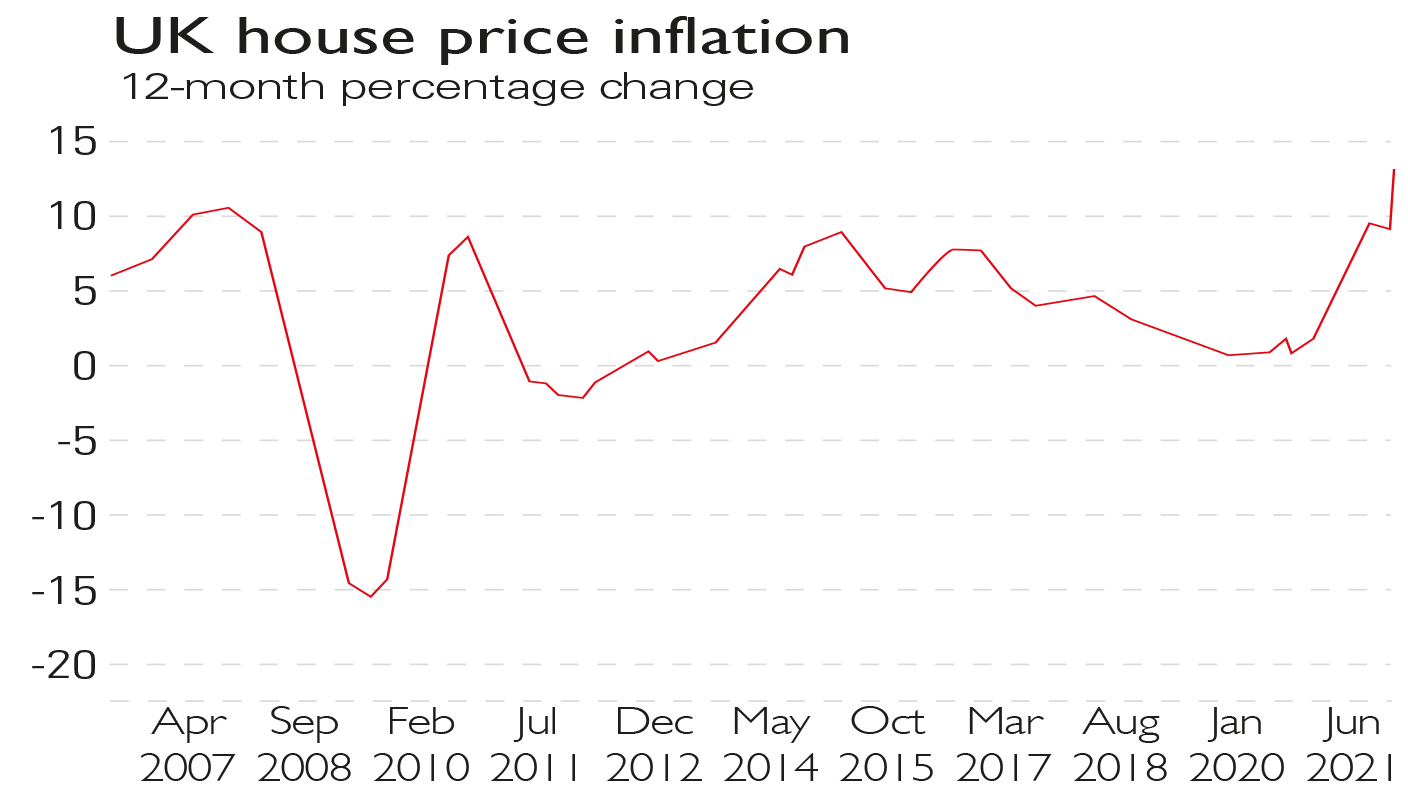

There will be “hell to pay” in the UK property market

“One day there is going to be hell to pay.” That’s Jeremy Grantham’s verdict on the UK property market. Why? Two reasons. First, it is overpriced, and second because while it is possible to get reasonably long fixed-rate mortgages (Nationwide has a five-year deal at just under 1%), in general, “you guys have floating rates, like Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. That means that when rates rise a large number of borrowers will see their monthly payments shoot up.

“Some of those borrowers will turn into forced sellers; given that markets are priced at the margin, prices will crash. In the US it won’t be so bad: we have fixed rates. So, yes, our market will crash and it will be painful, but not nearly as painful as it will be in Britain.”

What can we do? When it comes to mortgages, “go and get the longest one you can”, says Grantham. If the ten-year offering seems a little more expensive than you would like, “pay up a little” and get it anyway. You may feel as though you are overpaying for a while but that won’t make you wrong. “Everybody feels stupid at the top of the bull market, basically.” Everyone feels they should have taken more risk – leveraged their assets a bit more.

What usually happens however is that they capitulate and do just that “just in time to get wiped out... The market, in its own way, must have a lot of fun.” However this is not just about the UK. Housing in most of the world is about as bubbly as it has ever been. In the US, prices as a multiple of family income are now higher than they were in the great housing bubble of 2006 and 2007.

That “in itself is quite amazing”. And remember that when that bubble deflated it took $8trn of “perceived wealth” (“perceived” because the house itself doesn’t change just because its price rises) down with it. The same day of reckoning will come to global markets again. The only thing in the UK’s favour is how slow it is at building houses. Last time round the markets that really cracked – Spain, Ireland and the US – were the ones that built and built. Those that did not (the UK, Australia, and Canada) were not hit so hard.

However, there is little doubt in Grantham’s mind that we won’t escape so lightly this time. With prices up by 13.2% in the year to June (the data is from the Office for National Statistics – see chart) housing inflation is at a 17-year high. When the crash comes to the UK, says Grantham, it will be a “humdinger”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek Talks

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek TalksPodcast Clare Francis, savings and investments director at Barclays, speaks about money and mental health, why you should start investing, and how to build long-term financial resilience.

-

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change looms

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change loomsChanges to inheritance tax (IHT) rules for unused pension pots from April 2027 could trigger an ‘exodus of large defined contribution pension pots’, as retirees spend their savings rather than leave their loved ones with an IHT bill.

-

Three Indian stocks poised to profit

Three Indian stocks poised to profitIndian stocks are making waves. Here, professional investor Gaurav Narain of the India Capital Growth Fund highlights three of his favourites

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investors

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investorsThere are similarities to 2007 in private credit. Investors shouldn’t panic, but they should be alert to the possibility of a crash.

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both

-

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new look

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new lookThe beauty industry is proving resilient in troubled times, helped by its ability to shape new trends, says Maryam Cockar

-

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?Energy provider SSE is going for growth and looks reasonably valued. Should you invest?

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive