Lessons for investors from the 1800s

New data suggests that factors such as value, momentum and low beta have a long history of success

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The hunt for ways to beat the market means that the investment industry has an enormous appetite for data on how different types of stocks have performed over time. The problem is that the data we have is more limited than you might expect. It’s quite decent for US stocks back to the 1920s, for example, because in the aftermath of the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, American researchers began collating more financial and economic information. There are also long-term stock prices for many other countries, but there’s a shortage of long-term fundamental data.

This is an issue when you want to know whether a pattern of returns you have found only holds true for the limited amount of data you are working with (known as “in sample” in statistics), or whether it tends to occur across different markets and across time (“out of sample”). Findings that are only tested in sample will often be misleading – they may lead you to make wrong forecasts if you try to apply them more widely. Results that can be robustly replicated out of sample and in very different environments can be trusted much more as the basis for an investment strategy.

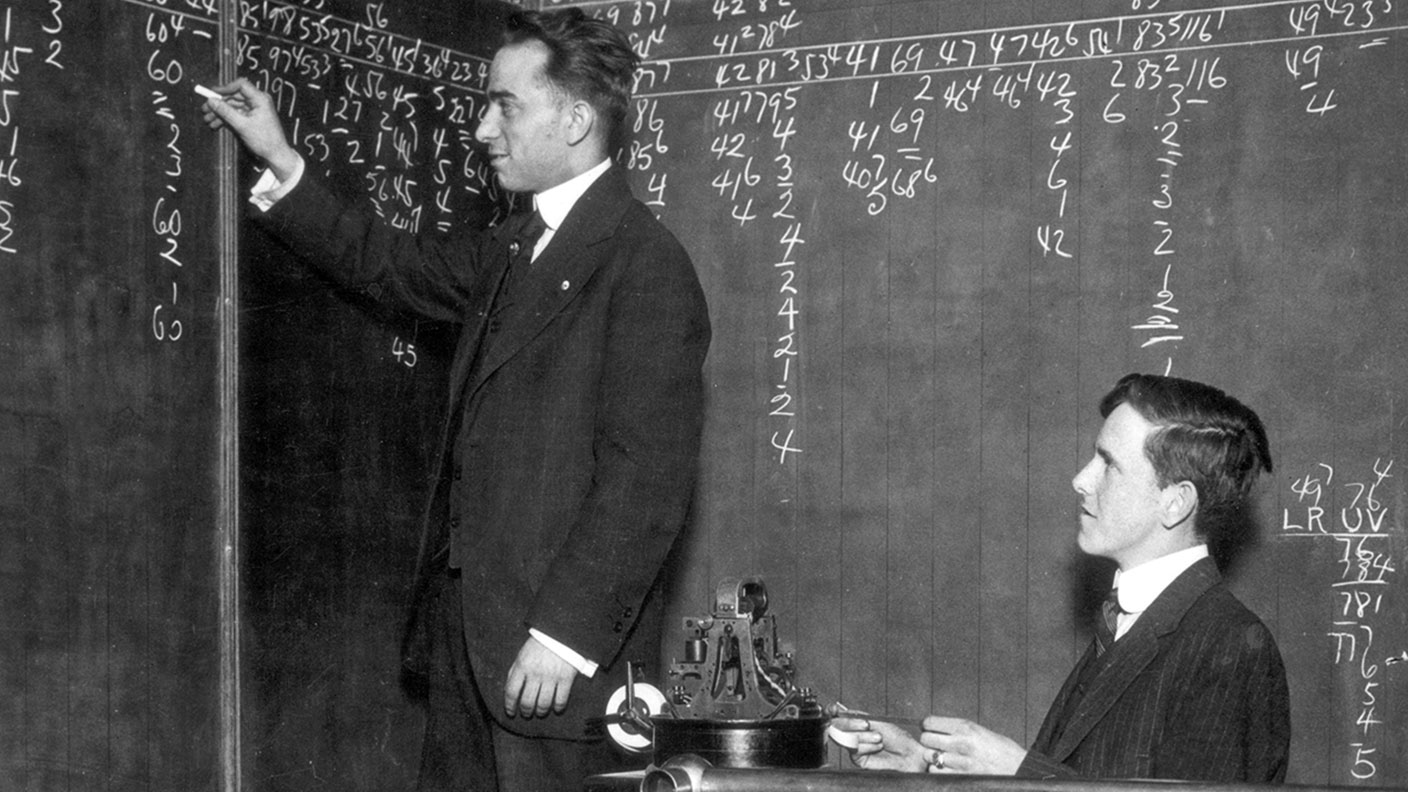

Reconstructing the past

So anybody interested in market history will be pleased by a new study from researchers at Dutch asset manager Robeco and Erasmus University at Rotterdam, who have put together data on US stocks from 1866 (when the country was just emerging from civil war) to 1926. This involved a great deal of work scanning old newspapers and other records to build up a database of 1,488 individual stocks (which explains why this kind of historical work is rare). The information available is limited – there are no earnings – but includes prices, market capitalisation and dividends.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This allowed the researchers to test whether factors (see below) such as yield, size and momentum worked in this very old, very different out-of-sample data in the same way that they have in more recent history. Their results suggest that yield and momentum effects were present, as was low beta (the tendency of less volatile stocks to outperform more volatile ones). The size effect (smaller stocks beating larger ones) was not significant (one could speculate that some issues driving small-stocks today, such as less public research and information, were true more broadly back then).

There is one huge caveat to historical studies like this. It is possible that any apparent anomalies could not have been profitably exploited given higher trading costs or lower liquidity. That aside, this data seems to strengthen the idea that many factor effects are long-term consequences of human behaviour in markets rather than misleading patterns that appear solely by chance.

I wish I knew what factor investing was, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

A factor is a characteristic that has been shown to contribute to a stock, bond or other security outperforming the market. Research into factors was originally driven by academics trying to figure out why certain stocks tended to generate higher returns than theories about efficient markets would have predicted. Widely accepted factors include size (the observation that small companies tend to beat large firms over time); value (cheap companies beat expensive ones); yield (high-yielding stocks do better than low-yielding ones); and momentum (stocks that go up just keep on going up). These factors will not always beat the market over any given time period, but they have generated superior returns in many different global markets over the long run.

Factor investing has become increasingly popular in recent years, as the investment industry tries to exploit both the rapid growth in computing power that makes it easy to construct indices based on different factors and the growing disillusionment with active fund managers. Factor-based strategies are often described as “smart beta” – a label that implies they fall between traditional index funds (which aim to deliver the market return, or “beta”) and active funds (which aim to deliver above-market returns, or “alpha”). Today, investors can easily buy a momentum ETF that constantly rebalances into stocks with strong momentum or a value ETF that holds stocks viewed as cheap on certain metrics.

The problem with the race to find new factors for smart-beta funds to exploit is the risk of data mining. If you look at enough historical data, you can always find patterns that turn out to be simply statistical flukes. However, the established factors (such as those listed earlier) are widely accepted as valid – although whenever they endure a long period of underperformance, there will be questions about whether they still work.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?