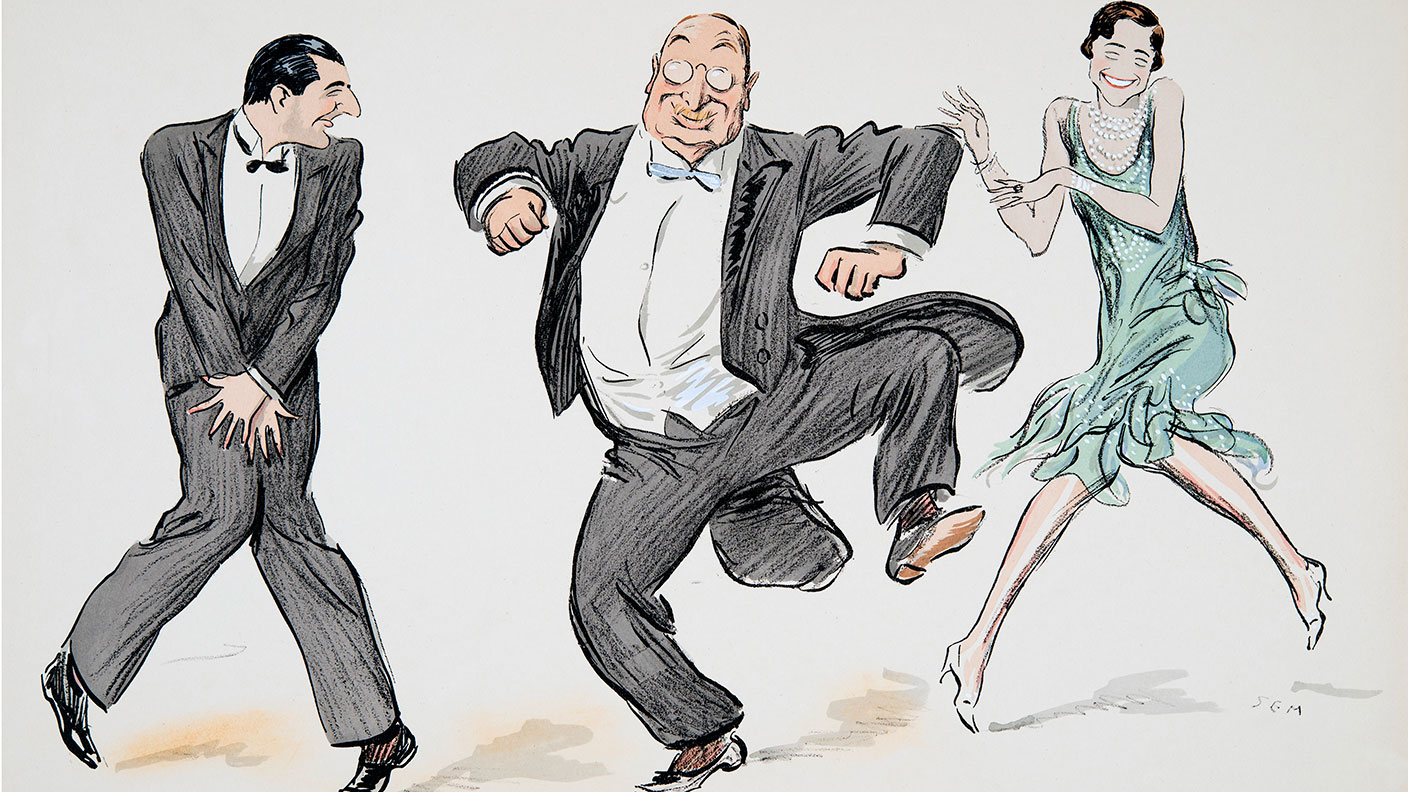

Will the post-Covid recovery set us up for the Roaring 2020s?

As we head into 2021 with at least two Covid vaccines showing extremely promising results, and more to come, we could be about to enter a period of unbridled optimism – a Roaring Twenties for the 21st century.

George Santayana is famous for observing that “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. Although arguably Tom Hanks was more on the ball when he suggested that “history in a societal sense doesn't repeat, rather it seems to rhythm”.

Of course we are not doomed to repeat the past, but economies and societies do tend to react in similar ways to shared processes. The 1920s saw the global economy recovering from a devastating pandemic – the mis-named Spanish flu – which had claimed millions of young lives so soon after the Great War.

Released from the pervasive sense of fear and foreboding, youngsters partied like never before. Economies boomed, egged on by stockmarkets that roped in millions of new investors who suddenly had access to speculation through new practises such as buying shares on margin.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The numbers are worth repeating. The 1920s saw the American economy grow by 42%, with GDP per head rising by not far off 25% over the decade. Stockmarkets dropped by 32% in 1920 but then shot up. The Dow Jones Industrial Average then rose from 71.95 points at the beginning of 1921, to a high of more than 381 points before the market crashed again in October 1929.

Could the end of Covid trigger our own Roaring ‘20s?

As we tiptoe into 2021, with at least two Covid vaccines already showing extremely promising results, and more to come, maybe we are about to repeat that optimism. Here’s one small example – earlier this month, analysts at US investment bank Morgan Stanley issued their most up-to-date strategy outlook, and the summary says it all: “Keep the faith, trust the recovery, and overweight equities and credit against government bonds and cash.”

Predicting a ’V-shaped’ recovery, greater clarity on vaccines and continued policy support, the Morgan Stanley global strategy team reckons that risky shares are in a sweet spot, with corporate earnings likely to grow by 25-30%, supporting double-digit total shareholder returns through to the end of next year.

OK, you might think – a rebound from a terrible global pandemic is one thing, but one would reasonably expect this surge in optimism to fade after a year or two. What on earth could keep this surge going for a decade?

Of course, prediction is a mugs game, especially ten years out – but maybe we can trace out some existing structural trends that might just accelerate over the 2020s. Let’s start with demographic factors.

Our societies are still aging at a rapid pace – some (such as China) more rapidly than others. This might trigger a phase of what’s called euphemistically called “wealth decumulation” – or in plain English, a diminishing pool of savings capital, as older investors sell up to fund their increased lifespans.

But there will also be a huge boom in intergenerational wealth transfers from baby boomers dying and shifting their property wealth to younger family members. These younger family members will suddenly inherit vast sums of money, some of which might find its way into stockmarkets. Don’t forget – these ‘youngsters’ are already dabbling more and more in stockmarkets, in part fuelled by the boredom of lockdown.

Yet it would be foolish to regard this younger generation as spendthrifts and speculators. Many once-standard purchases such as a new car or a new home are now hideously expensive, forcing many to embrace a more capital-lite rental model of living. This could result in additional spending on lifestyle experiences as a substitute.

That new interest in speculation is also, arguably powered by a very real imperative – the need to see higher rates of return in order to fund longer lives, courtesy of advancing life sciences. One might reasonably expect today’s 20-somethings to have an average life expectancy of at least 90. That’s a huge advance, but it means these younger, savvy, environmentally-conscious investors need an even bigger capital sum to last through their long retirement. There’s a limit to how much you can sensibly save, so the corollary is that we collectively seek higher returns, which are in turn a tacit acceptance of higher risk appetites.

Governments are going to spend much more money than we’ve been used to

Another tailwind behind a more exciting 2020s might be the arrival of vast amounts of state-directed capital expenditure. As China and the US limber up for a decade of competitive tension, it’s clear that their strategic rivalry will be fought mostly in the technological arena, courtesy of vast spending on research and development.

This might prompt huge advances, as China tries to build on its strength in big data and artificial intelligence, and regain some access to state-of-the-art semiconductor technology. A space race is also seemingly inevitable, and we know from the last one – in the 1950s and 1960s – that huge technological changes tend to flow through eventually to wider society.

The battle against the other, slower burning, global emergency – climate change – will also have an impact. Joe Biden in the US might not get all the money he wants for his big Green New Deal, but it seems inevitable that spending on clean energy will only continue to increase. And the private sector only needs a small amount of encouragement to invest in new power grids, renewables, batteries, and electric cars.

More pointedly, if Biden doesn’t get all he wants for his Green New Deal, he might encourage central bankers to step into the breach and use their printing presses to help fund new developments. Which brings us nicely to the elephant in the room – the next stages in monetary experimentation.

Anyone who seriously believes that central banks in the key developed world economies will now give up their tools and retreat to a more passive role is seriously deluded. Central bankers, starting with the most powerful – Jerome Powell, chief of the Federal Reserve in the US – have already gone on record as saying they’ll do whatever is needed to kickstart employment growth and build sustainable growth through the next decade.

What shape the new policies will take – negative interest rates, funding green infrastructure, helicopter money, dual interest rates – is up for debate. But there is zero sign that central bank balance sheets will decline any time soon. This has an inevitable knock-on impact on asset prices and especially on corporate bonds and equity prices, which have mightily benefited from existing monetary expansion.

The $64 trillion question though is whether all this extra government spending and monetary intervention will result in a savage blowback which will also echo the 1920s – increasing inflation and asset bubbles. If we are lucky, the changes above will result in another development, namely increased economy-wide productivity which will then raise growth rates.

The drivers for this increased productivity are probably hidden from view at the moment – if they are there at all. Perhaps more working from home and virtual employment might drive up labour productivity? Might all that extra technological innovation eventually feed through into economic growth, especially as China and South east Asia’s economy expand?

We probably won’t know if any of these forces have weaved their magic for a decade or so, but if they do, and our economies grow as fast as asset prices, then perhaps we might escape that last shadow of the 1920s – a massive stockmarket collapse and geopolitical turbulence.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

David Stevenson has been writing the Financial Times Adventurous Investor column for nearly 15 years and is also a regular columnist for Citywire.

He writes his own widely read Adventurous Investor SubStack newsletter at davidstevenson.substack.com

David has also had a successful career as a media entrepreneur setting up the big European fintech news and event outfit www.altfi.com as well as www.etfstream.com in the asset management space.

Before that, he was a founding partner in the Rocket Science Group, a successful corporate comms business.

David has also written a number of books on investing, funds, ETFs, and stock picking and is currently a non-executive director on a number of stockmarket-listed funds including Gresham House Energy Storage and the Aurora Investment Trust.

In what remains of his spare time he is a presiding justice on the Southampton magistrates bench.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.