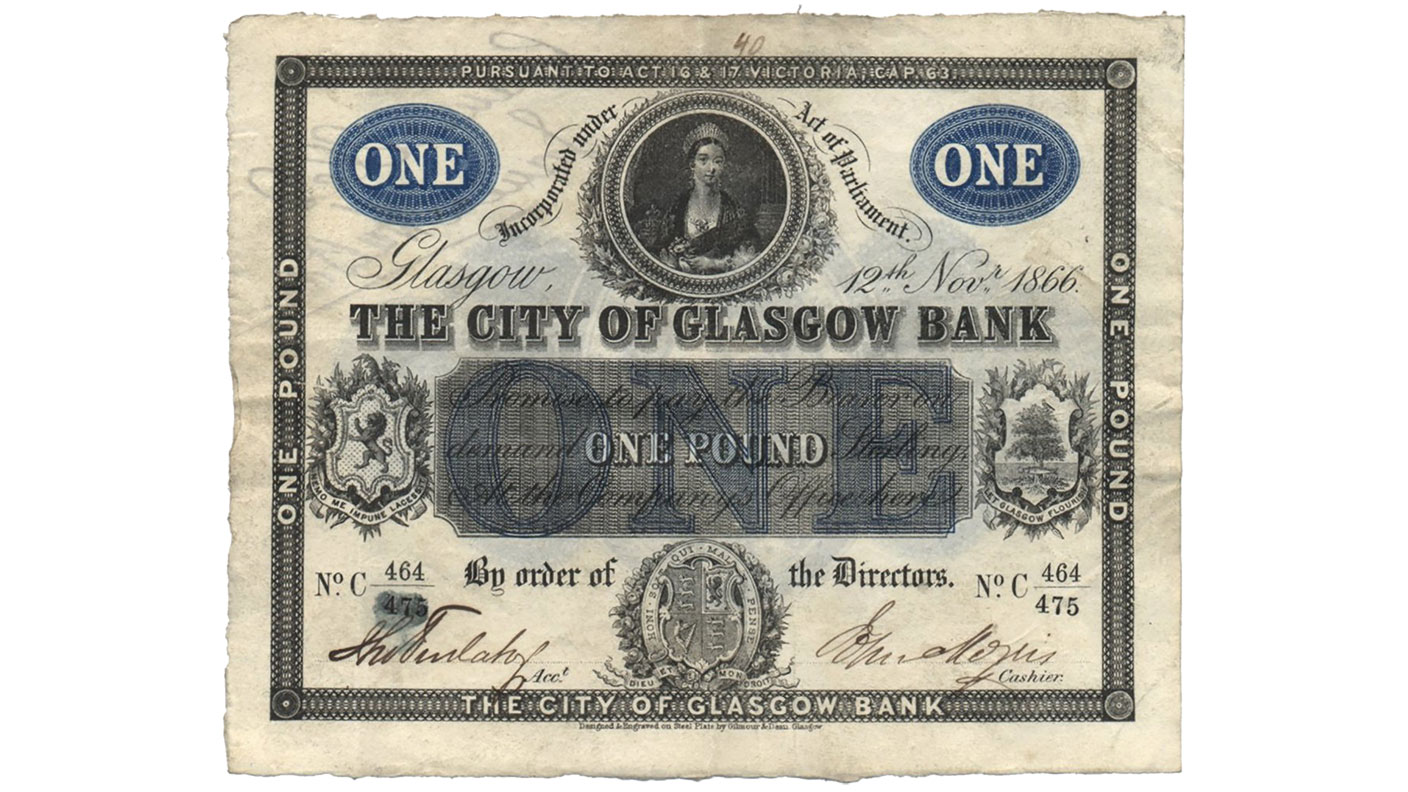

Great frauds in history: the bank that cooked the books

When loans made by the City of Glasgow Bank turned bad, its management falsified the balance sheet, overstated its gold reserves and issued false statements about its financial health.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The City of Glasgow Bank was founded in 1839 and quickly became one of Scotland’s leading lenders. It briefly shut down in the banking crisis of 1857, caused by the collapse of a rival bank, but it was able to reopen by the end of the year, thanks to support from other banks. By 1878 it had resumed its former importance, with 133 branches around Scotland, lending money to individual companies around the world, and was owned by more than a thousand shareholders and partners, who were personally liable for any debts.

What was the scam?

Contrary to its reputation as a successful institution, the City of Glasgow Bank was run badly. It held a large number of bad loans in risky companies, mainly mining and railway companies in the US, and later lent £6m (£586m in today’s money) to four companies in India. When these loans turned bad, the bank’s management simply falsified the balance sheet by overstating the value of its gold reserves and issued false statements about the bank’s financial health. In an attempt to shore up confidence, they secretly started buying shares to push up the price.

What happened next?

As late as the summer of 1878, the bank was supposedly solvent enough to pay a dividend of 12%. However, rumours that it was in trouble began to circulate in London and the bank was unable to refinance its short-term debts. This forced it to seek a bailout from other banks, which demanded a proper audit of its books. When this revealed that the bank was hopelessly insolvent, with a huge gap between assets and liabilities, it was forced to shut its doors for good, setting off a run on other Scottish banks. The bank’s manager, Robert Stronach, and its directors were later convicted of fraud.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Depositors were eventually repaid in full, but the shareholders’ personal liability meant that they were wiped out and ended up contributing an extra £5.4m (£528m). As a result, 1,565 of the 1,819 shareholders went bankrupt. The City of Glasgow Bank’s collapse shows the importance of making sure that your portfolio isn’t just focused on one industry or one part or the world. While the scandal effectively made limited liability universal for most shareholders, it’s important to know the exact terms of any investment to avoid any nasty surprises.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brands

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brandsConsumer brands no longer impress with their labels. Customers just want what works at a bargain price. That’s a problem for the industry giants, says Jamie Ward

-

A niche way to diversify your exposure to the AI boom

A niche way to diversify your exposure to the AI boomThe AI boom is still dominating markets, but specialist strategies can help diversify your risks

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom