Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

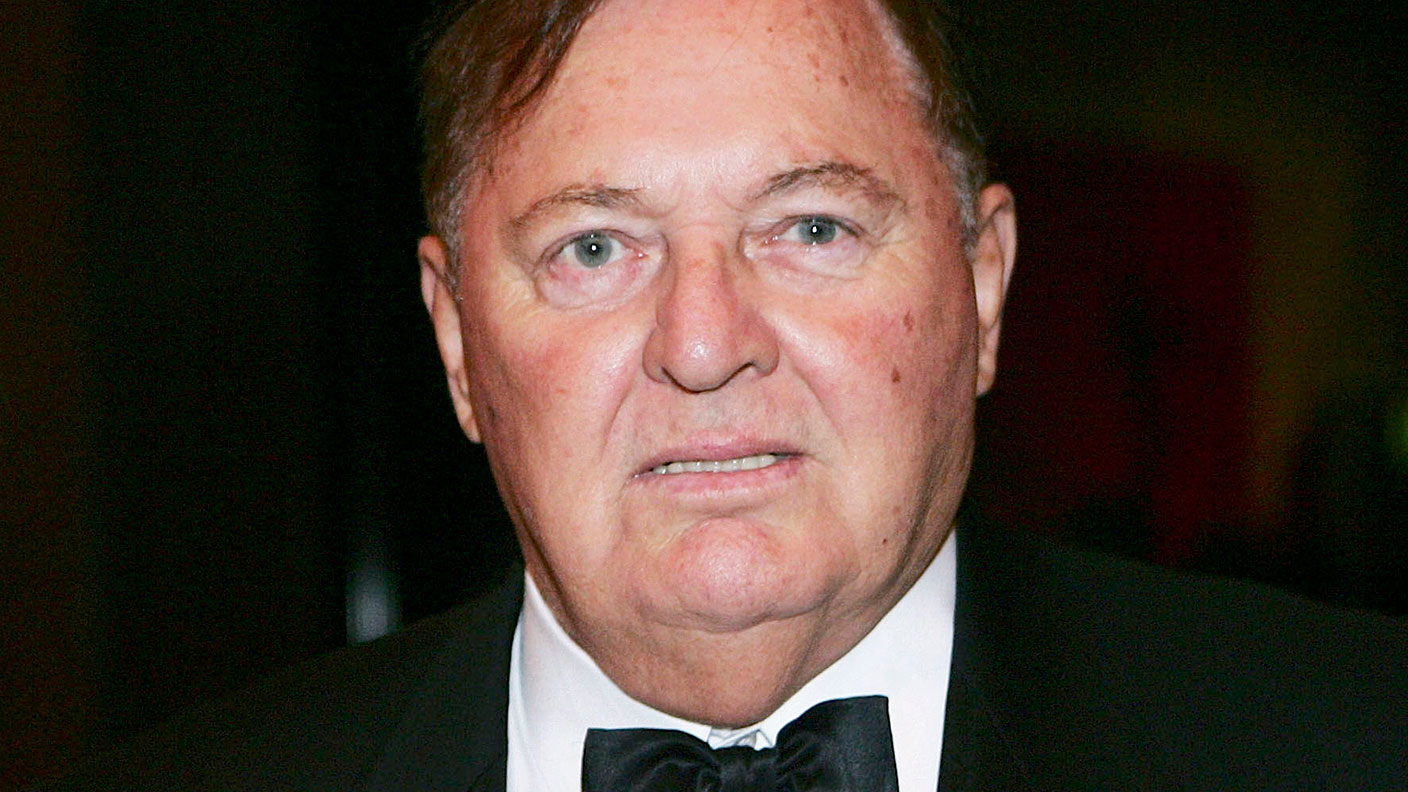

Robert Maxwell

What was the scam?

Having taken on large amounts of debt, and following the launch of a string of expensive failures, Maxwell was reduced to shunting money between his companies to give the impression they were profitable, repeatedly changing the dates on which they reported earnings, in order to fool auditors.

When this wasn't enough to keep his empire going, he looted money from the pension fund of the Mirror Group in an attempt to prop up its share price.

What happened next?

With his businesses on the brink of collapse, Maxwell was reported missing from his yacht on 5 November 1991. His body was later discovered in the Atlantic Ocean, an apparent suicide (officially considered an accidental drowning).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

His bankers called in their loans, and his looting of the pension fund was discovered. By 1992 his sons Kevin and Ian were forced to declare bankruptcy.

In the end, Maxwell's firms were liquidated and his sons were put on trial for fraud (they were ultimately acquitted).

Jordan Belfort and Stratton Oakmont

What was the scam?

Stratton Oakmont followed the traditional "boiler room" model of using high-pressure sales techniques to sell shares (which Stratton owned) in dubious companies to investors.

In many cases, Stratton would lure its clients in by allowing them to make a profit on their initial trade. It would also promise them a large allocation of shares in an initial public offering, only to later claim that the shares were only available at a much higher aftermarket price (created in part by phoney trades). Shortly after all the shares had been sold, the price would quickly collapse.

What happened next?

Stratton Oakmont was in trouble with the authorities almost from its founding in 1989, but it was not until 1996 that it was finally shut down. Even then it would take three more years for Belfort to be indicted for securities fraud and money laundering. Despite admitting to manipulating the stock of 34 companies, Belfort escaped with only a two-year jail sentence thanks to his decision to co-operate with the authorities (co-founder Danny Porush would get four years).

Belfort was also required to pay $110m in restitution. The Wolf of Wall Street, a book by Belfort based on his experiences, became a bestseller and was turned into a hit movie, but less than $12m has been recovered from the fraudster, mainly from the initial liquidation of his estate. The 1,513 people who were defrauded by Belfort have only received a fraction of the money that they lost.

ZZZZ Best

What happened next?

Stratton Oakmont was in trouble with the authorities almost from its founding in 1989, but it was not until 1996 that it was finally shut down. Even then it would take three more years for Belfort to be indicted for securities fraud and money laundering. Despite admitting to manipulating the stock of 34 companies, Belfort escaped with only a two-year jail sentence thanks to his decision to co-operate with the authorities (co-founder Danny Porush would get four years).

Belfort was also required to pay $110m in restitution. The Wolf of Wall Street, a book by Belfort based on his experiences, became a bestseller and was turned into a hit movie, but less than $12m has been recovered from the fraudster, mainly from the initial liquidation of his estate. The 1,513 people who were defrauded by Belfort have only received a fraction of the money that they lost.

How did it work?

It didn't the restoration service was completely invented. Minkow created a fake firm, Interstate Appraisal Services, which posed as ZZZZ Best's client. To keep the business running, Minkow took loans from various dubious figures, and shuttled money between bank accounts, in a Ponzi-style scheme. This deception was convincing enough for banks to lend him enough money not only to support an advertising blitz, but also to come close to taking over KeyServ, a competitor.

What happened next?

By May 1987, on the eve of the takeover, the Los Angeles Times published an article detailing that Minkow had previously been involved in $72,000 worth of fraudulent charges and was still refusing to pay some victims back.

This caused banks to pull their credit lines; the investment bankers overseeing the KeyServ deal forced an immediate postponement. At the same time it was revealed that some major restoration contracts that ZZZZ Best claimed to have won were made up. By July Minkow resigned as CEO, and was jailed a year later for various counts of fraud.

Asil Nadir and Polly Peck

What was the scam?

In order to fund this expansion Polly Peck took on a huge amount of debt. Meanwhile, in attempt to bolster investor and creditor confidence, Nadir systematically falsified the books, exaggerating profits and sales.

From 1988 onwards up to £378m disappeared from the company in the form of loans, dubious transactions and the re-registration of Polly Peck's assets under Nadir's name. While Nadir insisted that these were legitimate loans and were repaid, the evidence suggests they were mainly used either to prop up Polly Peck's share price, or were simply stolen by Nadir.

What happened next?

When they learned about the extent of the transactions, the board of directors demanded that the loans be immediately returned. Nadir refused.

With rumours circulating around the City of London, the company was raided by the Serious Fraud Office, causing its share price to collapse. Soon afterwards it filed for bankruptcy, with debts of £1.3bn. In 1993, Nadir was put on trial for fraud, but fled to Northern Cyprus (which has no extradition treaty with the UK), where he lived for 17 years.

The Bre-X gold-mining scandal

What was the scam?

As is standard in the mining industry, Bre-X's claims about its "discovery" were based on samples of rock drilled from the land it had acquired, which contained a relatively large amount of gold.

It later emerged that someone at Bre-X (possibly de Guzman) was "salting" the samples by adding gold flakes to them. Despite implying that its estimates were verified by a respected Canadian engineering firm, Bre-X kept all testing in-house and destroyed the samples.

What happened next?

Bre-X's deception came to light when an attempt by Barrick Gold to take over the site led Bre-X to agree to a joint venture with the Freeport-McMoran mining firm and an Indonesian fixer. Shortly after the deal was announced, a mysterious fire destroyed the firm's records.

De Guzman supposedly fell from a helicopter en route to meet with Freeport's executives (one of his ex-wives would claim he was still sending her money after his supposed death). Shortly afterwards Freeport announced it had found insignificant amounts of gold; this was confirmed by independent analysis. In May 1997, Bre-X filed for bankruptcy.

The original Ponzi scheme

How did the fraud work?

Ponzi quickly realised that, although the arbitrage opportunity was real, delivering the expected returns was a practical impossibility since it would involve buying more coupons than could be transported. Even satisfying the original 18 investors would have required him to buy and exchange 53,000 coupons.

Indeed, there is no evidenceof him exchanging any coupons. But rather than wind up the scheme, hedecided to raise more money from new investors, using their subscriptions to pay off the old investors. Initially, this worked well as the original investors spread news of the scheme.

What happened next?

Within months Ponzi was receiving huge amounts of money from across the US. As well as hiring more agents to solicit investors, Ponzi tried to keep the scheme afloat by taking control of a local bank.

By the summer of 1920 he was living a luxury lifestyle in a large mansion. Then an article in a local newspaper prompted an investigation and investors demanded their money back.In August Ponzi was declared bankrupt. By November 1920 he was jailed for fraud. He died in poverty in 1949.

Bernard Ebbers and WorldCom

How did the scam work?

To fuel the expansion, Worldcom took on a lot of debt. In order to keep creditors willing to lend money, as well as to meet the expectations of Wall Street analysts, WorldCom's management started fiddling the books to the tune of $11bn. Most of the fraud involved underreporting line costs (the amount that WorldCom had to pay for use of the telephone lines).

WorldCom did this by treating ordinary expenses as investment and dipping into funds set aside for future expenses. Overall, experts estimate that $7bn worth of line costs were hidden in this way.

What happened next?

Between 1999 and 2001 the share price started to fall due to the bursting of the tech bubble and regulators blocked a proposed merger with Sprint amid concerns about the company's debts. This placed Ebbers in a difficult situation as he had borrowed money against his Worldcom shares to fund his own companies, which meant that he had to put up more collateral each time the shares fell.

In order to avoid a fire sale, the firm ended up lending him $400m. By April 2002 WorldCom was facing increased pressure from its creditors, leading Ebbers to resign. The firm declared bankruptcy a few months later.

Calisto Tanzi and Parmalat

What was the scam?

To finance the merger spree, Parmalat borrowed huge sums of money. To ensure that creditors were willing to keep lending the company money, Tanzi began systematically falsifying Parmalat's financial statements, using complex derivatives and subsidiaries to hide the total amount of debt. He also exaggerated the number of assets held. Overall, Parmalat's true financial position was €14bn worse than that implied by its official balance sheet.

What happened next?

The first hint of problems came in early 2003 when the company suddenly announced that it was unexpectedly selling €300m worth of bonds to raise cash. The final nail in the coffin would come later that year when auditors questioned some of Parmalat's transactions with a mutual fund.

Within weeks, Tanzi was forced to resign, and then arrested, with the authorities discovering records covering €8bn of hidden transactions on his computer. After the firm missed a bond payment, the Italian government decided to put it into administration immediately in order to minimise the economic fallout.

The collapse of Enron

How did this work out?

Although legitimate, Enron's businesses were unprofitable.To hide this, the management fiddled the finances.It treated the total amount of money traded on its energy exchanges as revenue, for example (the standard practice is to count only profits and trading commissions).

It counted expected future profits from its deals as current profits. And to hide losses and mounting debts, it set up a complicated structure of off-balance-sheet "special purpose vehicles" to borrow money against Enron's stock.

What happened next?

While Enron's stock was rising, its creditors were willing to lend more money. But the bear market that accompanied the bursting of the technology bubble caused its share price to decline.

At this time The Wall Street Journal ran a critical article about Enron's accounting, causing other analysts to start to ask questions. With creditors now demanding repayment, and its credit lines drying up, Enron's executives were forced to admit that they had overstated earnings between 1996 and 2000, which made the problems even worse.

After rival Dynergy abandoned its planned bid for Enron, the company filed for bankruptcy in December 2001.

Theranos and the millennial Madoff

What was the scam?

The technology didn't work. Theranos was unusually secretive, forcing employees to sign non-disclosure agreements and refusing to publish scientific papers on its research.

It was later revealed that, while Holmes was making bold claims about the company's potential, and agreeing a deal with pharmacy chain Walgreens, the company's flagship device was so useless that the firm's engineers were secretly buying machines from competitors and performing screens with these instead.

What happened next?

The huge surge of publicity Holmes was fted by the press as a new Steve Jobs prompted journalist John Carreyrou to start asking questions. Richard Fuisz, who was engaged in a patent dispute with Theranos, put Carreyrou in touch with former employees, which led to a series of critical articles in

The Wall Street Journal. Government regulators shut down Theranos's lab in July 2016 and Walgreens ended its partnership. By August 2018, the company had been wound up.

Arthur Nadel’s day-trading scam

What was the scam?

Nadel claimed that he would make money for investors by day-trading the Nasdaq (a technology-heavy index of stocks) using a computer program. He was a poor trader, however, making only small returns during the technology boom, and large losses when the bubble burst.

To cover up his failure, he reported consistently large returns, which enabled him to keep attracting enough money to repay those few investors who wanted their money back. During this period, Nadel and the Moodys earned around $42m each in fees based on the reported performance of the fund and the amount of assets under management.

What happened next?

The global financial crisis in 2008 made investors nervous, resulting in increasing numbers demanding their money back, and a sharp decline in the number of new investors. Nadel suddenly disappeared in January 2009, days before the fund was due to repay $50m, leaving a letter for his wife confessing everything.

A few weeks later he handed himself in to the authorities, and was eventually sentenced to 14 years in prison. He died in jail in 2012. Neil Moody and his son, Chris, denied knowing anything about the fraud, but they accepted a brief ban from the securities industry as part of a settlement.

Nicholas Cosmo and the big gambles that turned sour

What was the scam?

Agape World claimed to make money for its investors through short-term real-estate loans designed to meet the need of those moving properties who require short-term liquidity. Cosmo did indeed try to find people to lend money to, but the return on the loans was far less than the high rates of interest that he was promising his investors.

At the same time, he started looting the business to cover his personal property speculation, his online futures trading (totalling $80m) and personal expenses. As a result, he came to rely on a constant infusion of new money to repay investors, turning his firm into a Ponzi scheme.

What happened next?

The scheme seemed to work well to start with, attracting plenty of new investors by word of mouth. In the financial crisis of 2008, however, investors started to demand their money back to compensate for losses that they had made on other investments.

When Cosmo told them they would have to wait, they hired a private investigator who discovered the fraud and alerted the authorities. Eventually, the US postal service and the FBI got involved, shutting down the scheme in early 2009. Cosmo would eventually be sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Nevin Shapiro’s groceries scam

What was the scam?

Shapiro claimed investors could make large risk-free returns of 10%-26% a year by lending money to his new company, Capitol Investments USA, which would use the cash to buy cheap wholesale groceries in one market and then re-sell them in another for more than the cost of transporting them.

To reassure investors, Shapiro produced falsified financial statements that disguised the fact that Capitol Investments consistently lost money and had effectively ceased trading after 2005. In reality, the entire scheme was a Ponzi-style fraud that repaid investors with newly raised cash and funded Shapiro’s lavish lifestyle – among his possessions were a $5m mansion and a $1m yacht.

What happened next?

By 2008, the supply of new cash had started to dry up and older investors started demanding their money back. Unable to make interest payments, Shapiro tried stalling them, proffering various promises and excuses, and giving away some of his jewellery and even his condo in the Bahamas.

Eventually, however, the numbers of irate investors mounted and lawsuits forced Capitol into bankruptcy in November 2009. Meanwhile, a tip-off from an irate investor prompted an FBI investigation, which led to Shapiro being convicted of fraud and sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2011.

The downfall of Ferdinand Ward – the "Napoleon of finance"

What was the scam?

Ward quickly dominated the partnership, making all the decisions, and persuaded Grant Jr and his father to invest another $200,000 into the business. When this capital was squandered through bad investments, Ward simply altered the books to give the impression that the firm was making money.

Greedy for cash to fuel an extravagant lifestyle, Ward then raised yet more money by launching a Ponzi-style scheme based on fictitious government contracts. Ward promised to pay investors interest rates of 10% a month, but no money was in fact invested, and investors were paid with funds raised from new depositors.

What happened next?

Fish’s Marine National Bank had heavily invested in Grant & Ward, financing this with a loan of $1.6m from New York City. By April 1884, the New York City comptroller decided to reduce the city’s deposits with the bank.

Despite an emergency loan of $80,000 from the tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt (underwritten by the former president), the bank collapsed, causing a minor financial panic and exposing Ward’s scam. Ward, who had briefly been known as the “Napoleon of finance”, quickly became the “best-hated man in the United States” and spent nearly seven years in jail.

Byrraju Ramalinga Raju and Satyam

What was the scam?

From 2001, in order to boost Satyam's share price, Raju began working with key executives, including those within the company's internal audit team, to systematically inflate profits, cash flows and assets. Raju and his team did this by creating false bank statements, customer invoices and even fake salary accounts.

The company also used forged board resolutions to obtain loans that were never declared on the balance sheet, using the money to keep the scam going. By September 2008, reported sales were 25% higher than actual sales, while assets were overstated by $1.47bn.

What happened next?

In December 2008 the company announced it was buying an infrastructure company owned by Raju's sons. The deal was approved by the board, but it generated a massive backlash from shareholders, along with the resignation of all the independent directors.

Raju was forced to confess publicly that he had been systematically defrauding investors, prompting the company's share price to collapse. Raju was arrested along with two other company executives. He was convicted of fraud in 2015 and sentenced to seven years in prison, but he remains out on bail.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

MoneyWeek is written by a team of experienced and award-winning journalists, plus expert columnists. As well as daily digital news and features, MoneyWeek also publishes a weekly magazine, covering investing and personal finance. From share tips, pensions, gold to practical investment tips - we provide a round-up to help you make money and keep it.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.