Great frauds in history: Arthur Nadel’s day-trading scam

When failed lawyer Arthur Nadel's hedge fund collapsed, it claimed to have $350m in assets. But it had just $500,000 in the bank.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

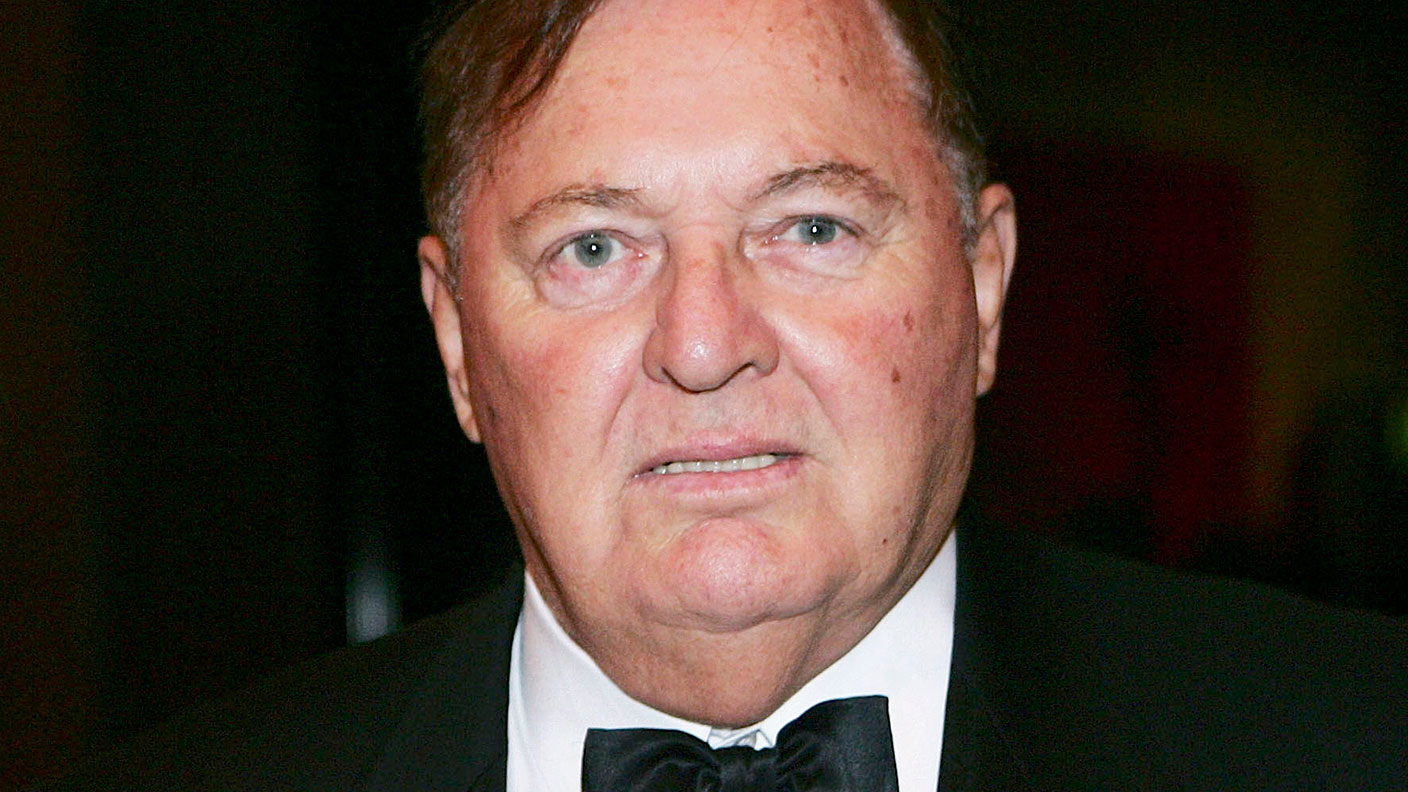

Arthur Nadel was born in New York on New Year’s Day in 1933. He went on to graduate from New York University (NYU), followed by NYU Law School. His law career came to an ignominious end when he was disbarred in 1982 for misappropriating money held in an escrow account (though the money was eventually repaid). Nadel then moved to Sarasota, Florida, trying out various business ventures, interspersed with stints as a piano player. In the 1990s he and his fifth wife, Peg, founded a successful day-trading club. On the back of this success he launched a hedge fund, Scoop Management Company, which managed money for three funds run by Neil and Chris Moody.

What was the scam?

Nadel claimed that he would make money for investors by day-trading the Nasdaq (a technology-heavy index of stocks) using a computer program. He was a poor trader, however, making only small returns during the technology boom, and large losses when the bubble burst. To cover up his failure, he reported consistently large returns, which enabled him to keep attracting enough money to repay those few investors who wanted their money back. During this period, Nadel and the Moodys earned around $42m each in fees based on the reported performance of the fund and the amount of assets under management.

What happened next?

The global financial crisis in 2008 made investors nervous, resulting in increasing numbers demanding their money back, and a sharp decline in the number of new investors. Nadel suddenly disappeared in January 2009, days before the fund was due to repay $50m, leaving a letter for his wife confessing everything. A few weeks later he handed himself in to the authorities, and was eventually sentenced to 14 years in prison. He died in jail in 2012. Neil Moody and his son, Chris, denied knowing anything about the fraud, but they accepted a brief ban from the securities industry as part of a settlement.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

At the time of Scoop’s collapse it claimed to have $350m in assets, but had only $500,000 in the bank. Actual investor losses totalled $168m, around half of which has been repaid through lawsuits and clawbacks from those investors who made money. Many investors put money into the scheme based on a fulsome recommendation from an independent investment newsletter, run by a neighbour of Nadel, which claimed to have done “due diligence”, but later turned out to have received nearly $10m worth of payments from Scoop. Investment newsletters can provide useful tips, but it’s always a good idea to do your own research.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?Graduates are complaining about their levels of student debt so should wealthy parents be helping them avoid student loans?

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.