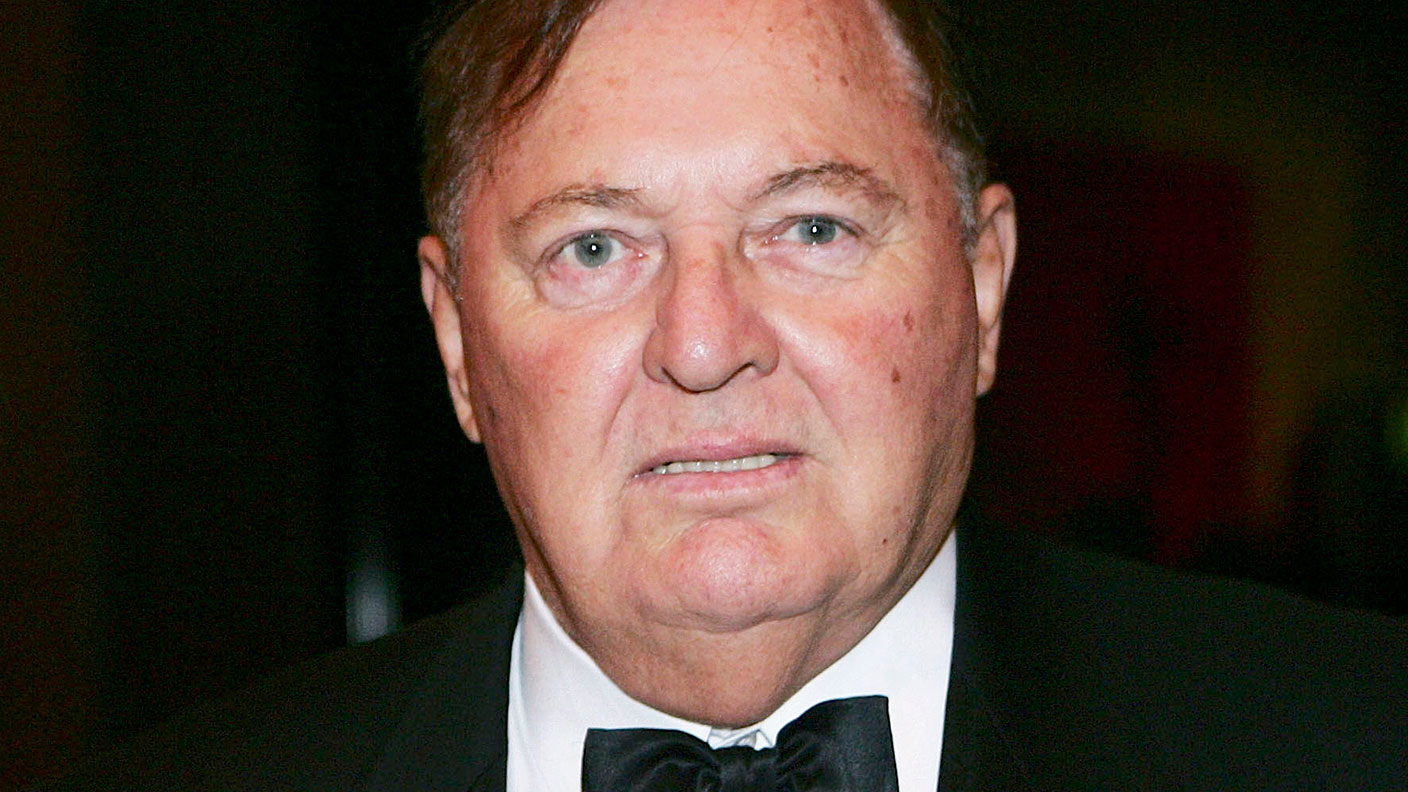

Great frauds in history: Sergey Mavrodi’s Ponzi scheme

Sergey Mavrodi turned his computer import business into a financial investment scheme and plundered hundreds of millions of dollars.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Sergey Mavrodi was born in Moscow in 1955 and went on to study at the Moscow Institute of Electronics and Mathematics before launching his own business. He was briefly jailed for black-market activity in 1983. In 1989, he took advantage of the end of communism to launch MMM. Initially, this was a business importing computers; it transformed into a financial investment scheme in 1994.

What was the scam?

Mavrodi sold shares in MMM, promising investors up to 3,000%-a-year returns for investing in newly privatised companies. In reality the fund was a Ponzi scheme, where money from new arrivals paid earlier investors. MMM’s TV adverts, which portrayed a simple Russian man who becomes rich via Mavrodi’s scheme, acquired cult status, and the fact that some people were indeed making huge fortunes from privatisation led to some five to ten million Russians buying in to the fraud.

What happened next?

The Russian authorities quickly became aware of Mavrodi’s scam, but were helpless to stop it because running a Ponzi scheme was not illegal at that time in Russia. As a result of the sky-high interest rates that the fund was paying, however, MMM quickly ran out of money and Mavrodi was briefly jailed for income-tax evasion. He then turned the tables on the authorities by successfully running for parliament (he claimed this was the only way investors were going to be able to get their money back), giving him immunity from further prosecution. Mavrodi was stripped of his parliamentary immunity in 1996, but he went into hiding and was not arrested until 2003.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What were the losses?

Some estimates put gross investor losses as high as $1.5bn, though this includes the fictitious balances of those who reinvested their “returns” and doesn’t take into account the winnings of those who withdrew their money before MMM collapsed. Still, there is no doubt a lot of people were left out of pocket. This didn’t stop Mavrodi launching a similar scheme in 2011, this time targeted at investors in Asia and Africa. Despite the fact that he was open about the fact there were no underlying investments, his scheme again attracted a large number of investors and was only halted by his death in 2018.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

Could you get cheaper loans under ‘significant’ FCA credit proposals?

Could you get cheaper loans under ‘significant’ FCA credit proposals?The Financial Conduct Authority has launched a consultation which could lead to better access to credit for consumers and increase competition across the market, according to experts.

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.