Gold miners should regain their shine – but choose carefully

Gold miners have struggled in recent years, despite the rise in the gold price. But this could be about to change.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The first piece I ever wrote for MoneyWeek was about gold miners. It was in 2006. "Buy this stock here," I said, with the easy confidence of a young man in a bull market. "It's 50 cents now, but it's going to be three dollars. As for that one there, it's a dollar. It will be five dollars by next year."

Every single one of these claims, made so casually because I knew no better, proved true. I must have tipped six or seven different stocks. There were doubles, triples, five baggers and ten baggers. I recommended one company, Gold Resource Corporation, below $2.The stock went up more than 15-fold to $30. Those bull market days are a long way away now. The bear emerged in 2011. In 2013 he took hold and, apart from six months of respite in 2016, he has refused to let go since.

Today, Gold Resource Corporation is one of the better companies in that it boasts producing mines and pays a dividend that is at $3.75. But that is one of the top performances. Many of the star companies of the 2000s do not even exist anymore some because they were taken out, others because they went to zero. Even the supposedly solid senior producers have been awful. Barrick costs C$16 today, 50% down on its 2006 price. Newmont sits at $32 when it was north of $40 12 years ago. Goldcorp touched $36 in 2006. This week it's $9.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

When you compare this performance with America's benchmark S&P500, which has roughly doubled in the same time frame, the opportunity cost is just staggering. But what is perhaps most galling of all is that gold itself is also roughly double where it was in 2006. Today the gold price sits at $1,225 an ounce. In 2006 it ranged between $500 and $720.

Why have gold miners missed the gold bull?

The received wisdom is that miners give you leverage to the yellow metal. If gold doubles, miners might triple or more. But this has not happened. You certainly get the leverage on the downside: when gold falls, the miners sell off by more. But the opposite has not occurred. The cumulative effect of this asymmetry is a situation where, even if gold is a lot higher than it was, the miners are a lot lower.

Some of the blame for this can be laid at the door of the miners themselves. They are often badly run. They have issued far too much paper. They bought unviable mines at the top of the market, which have since become write-downs. They have suffered from political and environmental risk. They have lacked discipline and financial rectitude. Companies have been run in the interests of management, not shareholders. Managements themselves have bought very little stock. But the companies are not entirely to blame. There is another factor at play here too.

Too much choice for gold investors

To understand this we need to go back to the 1930s. Homestake was the go-to stock of the decade. In the face of the Great Depression and a stockmarket that was in broad decline, Homestake, North America's largest gold miner, bucked the trend and multiplied many times over. The perceived wisdom was that something similar would happen in the great recession following the global financial crisis. And in fact there was a brief period in 2008 when this was the case. But it did not last. The broader trend in which gold outperformed the miners resumed.

Here's why. In the 1930s everyone was allowed to have up to 5oz ($100) of bullion coins. In 1932 President Roosevelt devalued the dollar as part of his New Deal strategy to kick-start the economy amid the Great Depression. The only way Americans could get any legal exposure to the gold price was by buying Homestake.

Fast forward to the 21st century and the reverse applies. There are umpteen different ways to buy gold or gain some kind of exposure to the gold price. You can go old school and buy coins or bars to store at home or in a safe. You can buy bars online and store them in a vault. You can buy the exchange-traded funds (ETFs). If leverage is your thing, you can buy leveraged ETFs, futures, options, CFDs or spread bets. Now there are over 100 gold-backed cryptocurrencies. The bottom line? There are so many ways to play the gold price that owning a gold miner and taking on all the accompanying individual company risk – the competence of the management, the geology of the mine, or even the local politics seems pointless unless there is some kind of special situation.

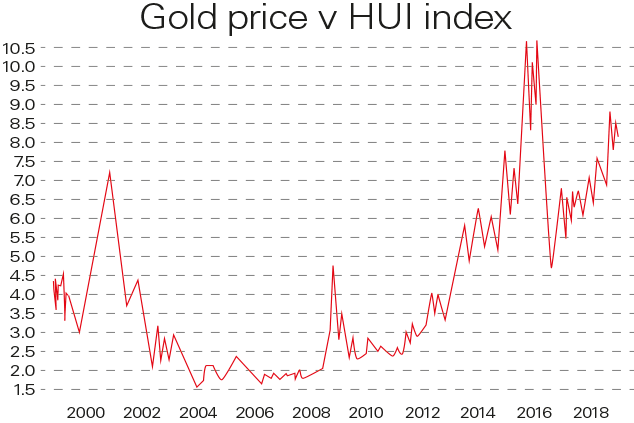

Miners and gold have diverged since 2006

The shoddy performance of mining operations relative to gold was masked for many years by the fact the gold price kept going up. Between 2001 and 2011 the gold price went from $250 to $1,920. As long as the metal was bullish, the miners were dragged up, even if the correlation between miners and metal was in structural decline. There were two periods of counter-trend action. One, as we have seen, was in late 2008, coming out of the stockmarket crash. The other was in the first six months of early 2016. Otherwise miners have underperformed.

Consider the chart above of the ratio between miners and the metal over the last 20 years: the HUI index of gold versus unhedged gold miners. Hedged miners sell their gold before they have mined it to guarantee a certain price, a habit many developed during the long bear market of the 1990s. Hedging reduces the scope for losses during a bear market by shielding you from future price falls, but it also means you are likely to miss out on gains when the tide turns and drives gold above the price you agreed. Unhedged miners, therefore, do best in a bull market. When the chart is rising the metal is outperforming the unhedged miners; when it is falling the miners are outperforming. The broader trend has been inexorable since 2006. Compared with the period from 2000 to 2004 that is some considerable underperformance.

Miners that have bucked the trend

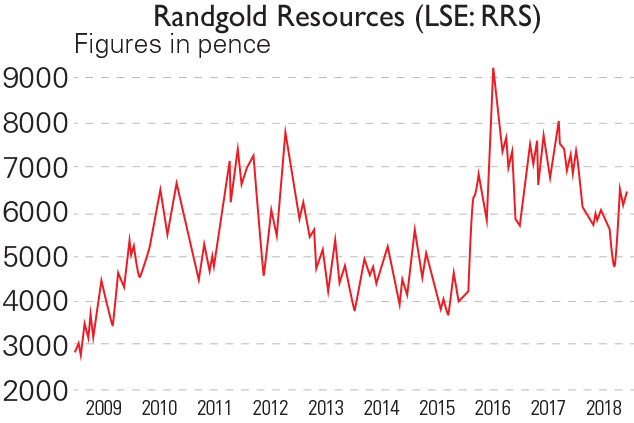

There are examples of companies that have bucked this trend.

Randgold Resources stands out in this context. Its boss, Mark Bristow, successfully constructed a plethora of mines across Africa and his stock has gone against the broader trend – dramatically outperforming the metal, in its early years at least. There are other examples of competent management companies that have excelled in the business of either exploring for, developing, building, or operating a mine. But anything less than excellence, or a notch or two under that, has met with disappointment. If you are to have any success in today's market as an investor, you cannot accept anything beneath a first-class performance by the company you invest in. Otherwise, you will lose your shirt. Conditions are that hard. Bear markets are like that.

A bull market needs buzz...

Gold-mining exploration and development relies on hype. Promoters need to hype properties before they have been mined in order to raise the money to mine them. The better they hype them, and the better the industry backdrop, the easier it is to raise the cash they need and the better the price they can mine it at. The same logic applies to all bubbles. They accelerate investment.

With that accelerated investment essential infrastructure gets built more quickly than it otherwise would. The hype around dotcoms got the infrastructure around the internet built. The hype around railways in the 19th century got the tracks laid and the stations set up. Even if many investors lost money, the broader industry benefited. This is why we need bubbles. Mining, more than perhaps any other industry, is reliant on them.

But the problem is that after a bubble has popped it takes a long time for the narrative that drove the previous bull market to take hold again. Bad memories linger and it is very hard for any promoter to hype anything credibly when the sector is so visibly disappointing. Granted, we need better practice by gold-mining companies. Fewer Ferraris, private jets and nights at the Savoy would be a start, although the decadence witnessed among executives at the peak of the boom has, thankfully, largely disappeared. It would also help if there were fewer scams.

Where will the buzz come from?

Above all, however, we need a rising gold price and that we do not have. Beneath every bull market in gold-mining stocks is the fundamental case for gold. This is a strong story. Gold is money. It is a store of value in turbulent times. It is nobody else's liability. You can buy a similar amount of food, clothing, shelter or energy with the same ounce of gold that you could buy ten, a hundred, or a thousand years ago. Its value never deteriorates. People are always going to want gold.

The problem is, today they don't particularly. Over the last five years, the gold price has meandered between $1,050 and $1,400. Inventory levels in the main exchange-traded funds are close to record lows. Even Google searches for "buy gold" are down. Long gone are the days when a sign saying "we buy any gold" could be seen on every street corner.

Of course, we "should" be in a bull market. There are a million reasons why the gold price "should" be going up. The outlook hasn't been this gloomy in years. The threat of inflation lurks; interest rates outside the US are still extremely low (gold has no yield so it looks relatively appealing when rates are depressed); quantitative easing (money printing) and currency debasement continue; governments keep running up colossal budget deficits; the bond markets look as though they are on borrowed time; political unrest seems to be growing; and trade wars loom. Yet none of it seems to matter.

Expect a bounce

Since 2006, the other period of outperformance by the miners was in the first six months of 2016. The market was brutally oversold and sentiment was bitter beyond belief. There is a possibility a similar relief rally is not far away. There are many parallels, not least that bearish sentiment is almost as bad now as it was back in late 2015. The market could not be more indifferent to gold mining: fertile ground for a change in trend.

That remarkable rally in early 2016 (there were five baggers galore) followed the December tax-loss selling season. In North America, come December, investors sell their losers to offset the tax gains of their winners, and so oversold stocks become even more oversold.

Both 2017 and 2018 have been horrible in mining, and as a result I can say with almost total confidence that this year's tax selling, which begins now, will be brutal. There are going to be bargains galore. There is a very strong case for scooping some up with a view to selling them again before the end of February. Unless there are visible signs that the market is stronger than that, the time frame is that narrow. This would be a speculative bottom-fish with all the associated risk. It is hard to justify any longer-term investment in this sector without some demonstrable excellence on the part of management or some special situation, such as a unique discovery. These are possible to find, but the scope for error is huge.

My attitude will change if circumstances change, of course. But without the underlying support of a bull market in gold, this market is not going anywhere. Nonetheless, perhaps my saying all this in a MoneyWeek cover story is contrarian bullish: perhaps this article in itself will mark the low.

The miners set to shine

September saw the biggest merger in gold-mining history as London's largest listed gold miner, Randgold Resources (LSE: RRS), merged with Barrick (NYSE/Toronto: ABX), once the world's largest gold-mining company. Barrick had, at the time, a market cap of roughly $12bn and Randgold roughly $6bn, so at $18bn it was some merger.

If I had been a Randgold shareholder, I would not have been crazy about the deal. Randgold's outspoken chief executive, Mark Bristow, will become president and CEO of the new company, while Barrick's executive chairman, John Thornton, remains chairman.

But I can't help thinking this was more a takeover by Randgold of Barrick than the other way around. The smaller company wanted to get its hands on Barrick's assets. Given Bristow's track record with Randgold, you rather think he will shape up the new company and its operations.

Some assets he'll sell, some he'll restructure, but you get the impression that within a year or two, Barrick, hitherto a perennial underperformer, will turn a corner, at least as far as its day-to-day operations are concerned. So if you want a play on a senior gold explorer, Randgold/Barrick is probably the one to go for.

Newmont has, as a result of this deal, lost its status as the world's largest gold-mining company. Given machismo, you can't help thinking it would want that positionback. One way it could quickly retake it would be for it to buy out B2 Gold (NYSE: BTG). Newmont's market cap sits around $17.5bn, while B2 Gold's is about $3.25bn.

B2 Gold has producing assets in Nicaragua, the Philippines, Namibia and Mali, and is also developing properties in Burkina Faso and Colombia. The real jewel in its crown is the Fekola mine in Mali, which is proving to be a major cash cow for the company. The balance sheet is good, but you rather suspect that a $4.5bn offer would swing it for Newmont.So B2 Gold is my tip of the smaller large caps or mid-tiers, depending on what you want to call them. It's the best-in-show in this category of potential takeovers.(I hold shares in the group.)

I also have a fairly sizeable position in Regulus Resources (Vancouver: REG), which is developing a large copper-gold-silver project in Peru called AntaKori.

Regulus is a development play: you are basically betting the company's exploration lives up to expectations and it then gets bought out. Regulus's current market cap is about C$125, and it trades around $1.50, although it is not very liquid.

Initial drilling results at AntaKori have been extremely encouraging. Management is reasonably prudent. There is, I gather, enough cash to get it through all the drilling planned for 2019. In that same casual way that I dished out calls for doubles and triples back in 2006, I'm rather hoping this will double or triple before it gets taken out in three years time at $5 or something.

BHP Billiton recently took a placement in SolGold (LSE: SOLG), a huge exploration play in Ecuador at 45p. Newcrest Mining also owns stock. You suspect one of them will eventually take the firm out. Given the stock is currently trading at 36p, there is a slight discount to be had to the 45p BHP paid.

There is no doubting the potential of the resource here. The problem? Ecuador. Ecuador is hardly the most mining-friendly country in which to operate. I don't own shares in this one. This is definitely a stock for the brave.

All prices and information correct at the time of writing.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Marc Shoffman is an award-winning freelance journalist specialising in business, personal finance and property. His work has appeared in print and online publications ranging from FT Business to The Times, Mail on Sunday and the i newspaper. He also co-presents the In For A Penny financial planning podcast.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge