Trump’s economic legacy

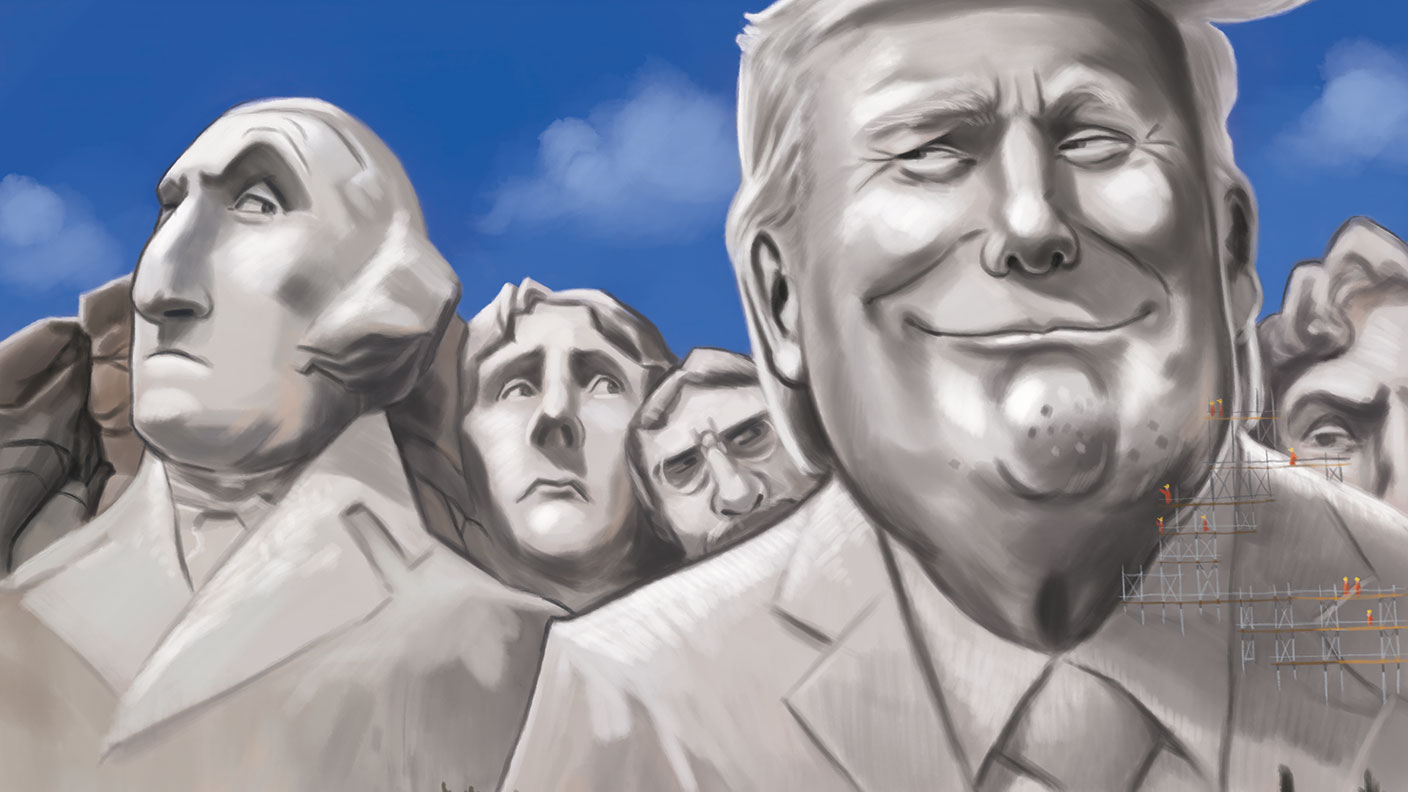

If the polls are right, Donald Trump will not be president of the United States for much longer. But right or not, what did he manage to achieve in the White House?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

How has America's president done?

Despite having to deal with a hostile press and political establishment, he’s had some wins. Take foreign policy. Critics charge Donald Trump’s nakedly transactional approach to international relations with putting the Western alliance and the international system under severe strain – to the despair of many of America’s long-standing friends and the grateful disbelief of Moscow and Beijing. And indeed, Trump’s fellow-feeling for authoritarian “strongman” leaders has been well-documented. Vladimir Putin struggled to keep a straight face at the July 2018 Helsinki press conference after his one-on-one with the US president – Trump lauded Putin’s “extremely strong and powerful” denial that Russia had tried to interfere in the 2016 US presidential election. But in terms of Trump-era foreign policy, two key events stand out – the bizarre geopolitical theatre that saw him attempt to cut a deal with North Korea and the deal brokered by him between the UAE and Israel – an accord that signalled a “significant shift in the balance of power in the Middle East”, says the BBC, and presented by Trump as a major foreign-policy coup.

But it’s the economy, stupid?

On the economy Trump has a strong claim to a positive legacy – and one that explains why, pre-Covid-19, he stood a fair chance of re-election. For all Trump’s obsession with short-term moves in the stockmarket, the long view is that Trump inherited a growing economy, and it kept growing on his watch. The pace of growth increased a bit in his first two years in office and America did notably well relative to other major economies, before growth slowed down a bit in 2019. What’s more, thanks to a decade of growth, wages were finally rising in real terms, even for lower-income workers. Trump’s overall economic record is problematic, says Josh Barro in New York magazine, partly because his tax cuts were so skewed to the rich. But he deserves credit for getting some big decisions right – for example, in appointing a Federal Reserve chairman, Jerome Powell, who focused on growth (rather than the spectre of inflation) and kept interest rates low.

Did Trump’s tax cuts work?

Trump’s early cuts in corporation tax did raise post-tax profits, which is one reason the US stockmarket has done relatively well under this president, says The Economist. Yet the long-term boost to growth from Trump’s tax reform is estimated at a mere tenth of a percentage point per year or less. The US has also attracted more foreign direct investment. The irony, though, is that a “crude stimulus to growth” might not have been needed were it not for Trump’s trade wars and tariffs, which “hurt confidence and weighed on global growth”. Overall, research suggests that tariffs have pushed up consumer prices by 0.5% and destroyed more US manufacturing jobs than they created (by making imported parts more expensive and inviting retaliation from other countries).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

And deregulation?

The administration says that its bonfire of red tape eliminated $51bn of regulatory costs between 2016 and 2019. But that is only about 0.2% of one year’s GDP, says The Economist. It also ignores any public benefits from regulation and there has been scant sign of the promised boom in business investment. Trump deserves some credit for steady growth and the best labour market in years. But “despite that, he is overselling Trumponomics. It was both a help and a hindrance”.

What about the public finances?

My verdict on the US economy under Trump would be “a modest acceleration from an unexpected source”, says Jon Hilsenrath in The Wall Street Journal – that source being government spending. The US federal deficit grew steadily under this Republican president, before ballooning this year to around $3.3trn, or 16% of GDP – the highest since World War II. Trump’s most lasting (if partly “unintended”) economic legacy will be to shift the economic conversation towards protectionism and away from deficits, argues Patricia Cohen in The New York Times. No matter who wins next week’s election, future US economic policy is “likely to pay more attention to American jobs and industries threatened by China and other foreign competition and less attention to worries about deficits caused by government efforts to stimulate the economy”. In theory, the unprecedented trillion-dollar deficits run up by Trump (by cutting taxes and raising spending) should have “caused interest rates and inflation to spike and crowd out private investment. They didn’t”. Paradoxically, the main beneficiary could be a president Joe Biden: Republicans will find it harder to attack Democrat spending plans as fiscally irresponsible given the past four years.

Does Trump deserve re-election?

No, says Jennifer Rubin, a conservative commentator who is hostile to Trump, in The Washington Post. His failure to counter Covid-19 is an economic catastrophe as well as a human one, she says. Blinded by the need to run for re-election on the economy, he first tried to downplay the pandemic and has “refused to understand that without a strategy to control the spread” of the virus “we will not enjoy a sustained economic recovery”. Even so, says Irwin Stelzer in The Sunday Times, the US economy is in “far better shape than we dared expect only a few months ago”. Some analysts think GDP will end the year only fractionally lower than 12 months earlier and America will probably be the best-performing G7 economy in 2020, perhaps by some margin. So if it really is the economy, stupid, it’s not clear who Americans should vote for. Those who want to see an end to the “chaos and vulgarity” of Trump must “bear the risks that Biden’s programme creates for the recovery. Neither an empathetic Trump nor a risk-free Biden is on the ballot”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn