Will the internet break – and can we protect it?

The World Wide Web, or the internet, is a delicate global physical and digital network that can easily be paralysed. Why is that, and what can be done to bolster its defences?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What's the issue with the internet?

The vast majority of the world’s population relies on the internet every day for work, communication, banking and social life. But the network’s ubiquity means that its frequent collapses and outages, and vulnerability to attacks by malign actors, are becoming ever more worrying. In October, a minor technical problem at an Amazon facility in Virginia knocked out Instagram, Hulu, Snapchat, Reddit and ChatGPT. Internet-connected devices – from smart speakers to fancy temperature-changing mattresses – malfunctioned in their millions. But that was pretty minor stuff. In July 2024, about 8.5 million computers worldwide suddenly crashed, displaying blue screens and leaving businesses struggling. The outage was linked to CrowdStrike, a security vendor for Microsoft, and the issue was caused by a bug in a routine software update.

Why is the internet so fragile?

Because beneath the gleaming, gigabit-broadband surface lies a patchwork of ageing infrastructure, brittle protocols, concentrated corporate control and geopolitical tensions that routinely push the global network to its limits. Some of that fragility relates to how the internet originally grew – ad hoc, and in a cooperative spirit of amateurism – and the way it has since developed. It’s vulnerable because there are so many working parts, both digital and physical. The internet sits on a gigantic global network of complex physical infrastructure – from the undersea cables that circle the globe to vast server farms in Virginia run by Amazon Web Services (AWS).

Are the undersea cables protected?

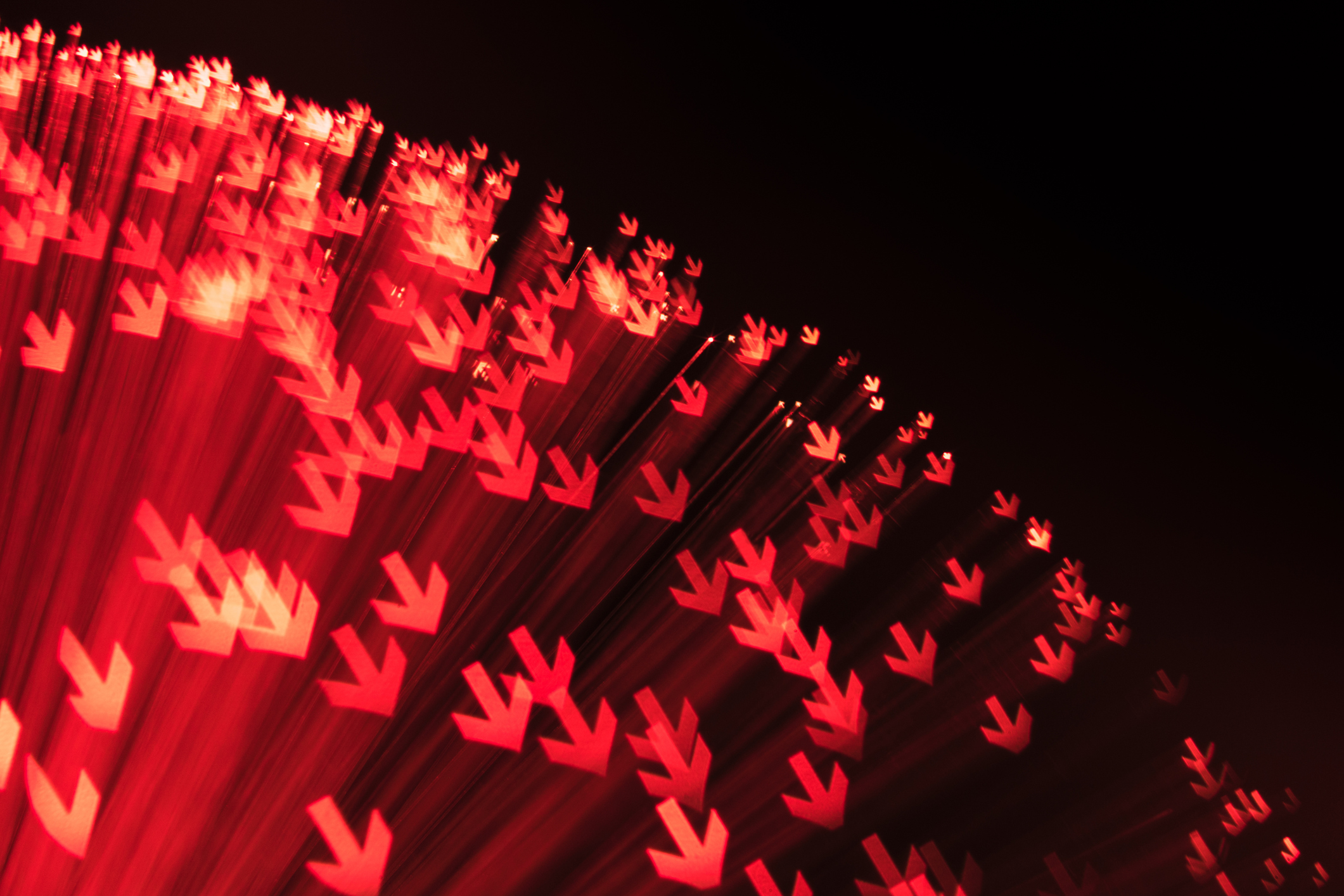

More than 95% of global data travels through roughly 550 fibre-optic cables laid across the seabed. But far from being futuristic, these cables are highly vulnerable to very mundane threats – fishing trawlers, ship anchors – as well as earthquakes, landslides and sabotage by malign state actors. Repairs by specialist ships take days or even weeks. Naturally, the corporate giants protect their assets. But when technical issues disrupted operations at Amazon’s Virginia facilities in October, it temporarily crashed the internet for users around the world.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Internet Exchange Points

At a more local level, the internet relies on Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) – warehouse-sized facilities where networks interconnect – which handle vast amounts of national and international traffic. There are thousands worldwide, but a relatively small number handle an outsized share of global traffic, making them critical single points of failure. If an IXP goes down because of a fire, power failure, or cyberattack, large chunks of the global internet can disappear along with it.

What is the internet's digital structure?

The internet is inherently fragile because it’s a complex network – indeed a network of networks made up of millions of nodes – in which very small causes can have enormous global effects. Every message sent travels through a labyrinth of servers, routers, cables and sometimes satellites. Many digital services rely on the same gateways, load balancers, identity checkpoints and routing layers. A Cloudflare configuration file growing past its limit, a DNS pointer inside AWS vanishing, a Google service-control routing rule drifting – all these small glitches can pull whole systems sideways, with cascading global impacts. But even if the physical network were flawless, and the digital architecture impregnable, the internet would still be fragile thanks to the protocols that keep it running.

How internet protocols work

The most basic – or notorious – is the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), which directs traffic between networks, but was never designed with security in mind. One mistaken update – or malicious reroute – can send traffic spiralling into black holes or hostile servers. Meanwhile the Domain Name System (DNS) – the internet’s address book, with its familiar suffixes – is technically decentralised, but in practice heavily reliant on a few major operators.

If one of these is attacked or fails, users can find themselves unable to reach major parts of the web, even if the websites themselves are perfectly healthy. Neither of these vulnerabilities are bugs in the system; they are legacy features of the early 1990s, when the internet became a mass-user network in a far more trusting and less interconnected era. Even today, says The Economist, the people who maintain the open-source code on which the internet operates often do so in their spare time.

Does the Cloud boost resilience?

No. The growth of the cloud, pioneered by Amazon, has made the internet more vulnerable and its control more centralised, says Will Gottsegen in The Atlantic. Once, setting up a website meant buying physical servers, procuring software licences and writing foundational code from scratch. Now, for a monthly fee, AWS and a few others own the servers and pre-write the code. The servers “are consolidated under a handful of companies”, so are the potential points of failure.

How can we strengthen the internet?

Widely cited ideas include overhauling critical protocols like BGP with built-in authentication; diversifying physical infrastructure, including more international cable routes and more regionally distributed IXPs; adopting multi-cloud strategies so organisations aren’t dependent on a single provider; building far more security into internet-dependent consumer products; using regulation to foster greater diversity of suppliers in web services; and establishing global norms, modelled on the rules of warfare, that prohibit targeting civilian infrastructure in cyberspace. The internet doesn’t have to be this fragile. But first we need to recognise how fragile it truly is.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems