Trump’s tariffs: what is he thinking and how should the UK respond?

Every right-thinking person knows that free trade is a surer route to the wealth of nations than protectionism, says Stuart Watkins. So, what is Trump thinking?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

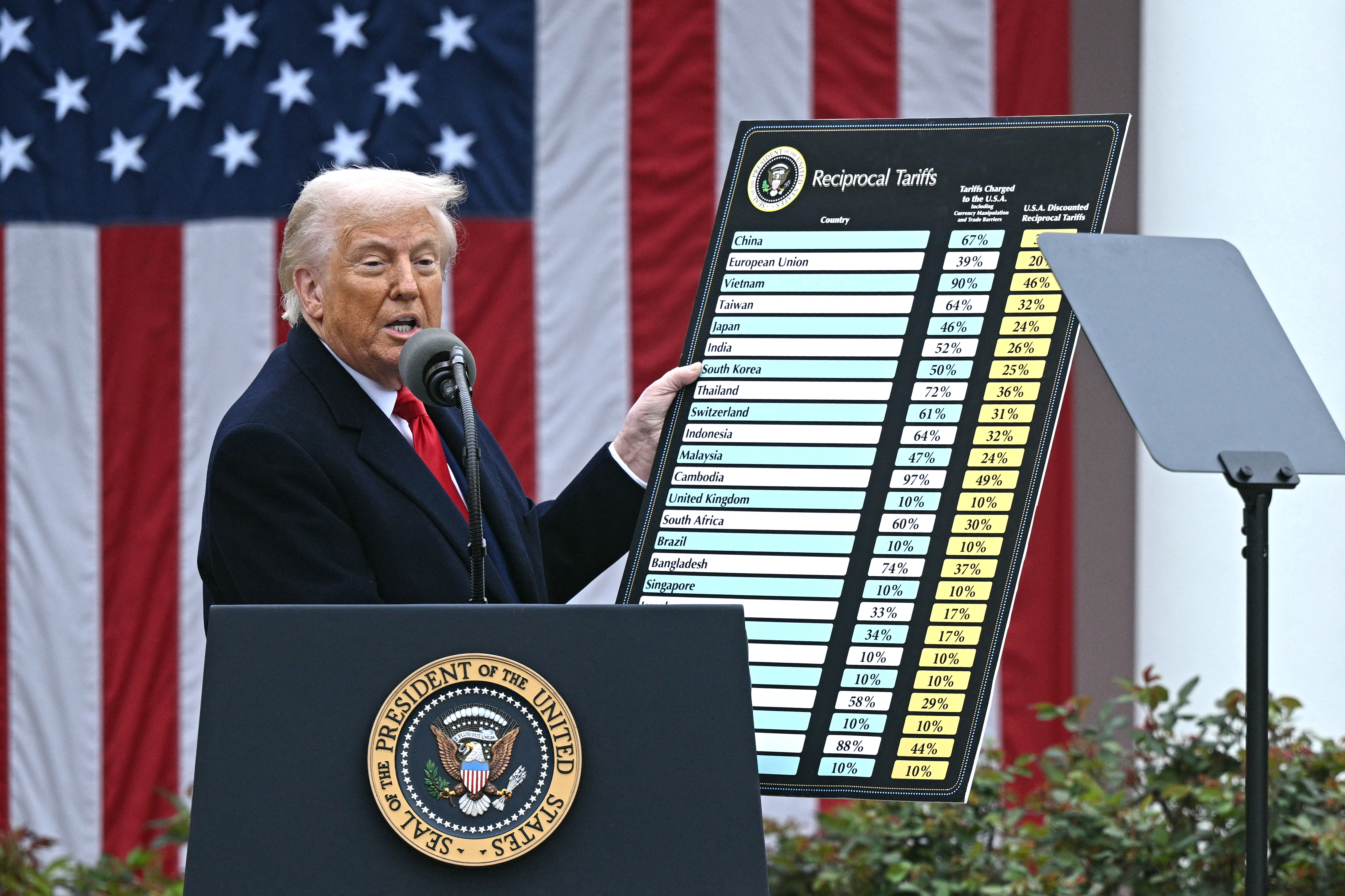

The consensus among mainstream economists and policymakers is that tariffs are bad for the economy and ultimately self-defeating. Slapping charges on imports to make them more expensive and thus protect industries at home leads to economic inefficiencies, reduced competition and hence innovation, and a higher cost for imported goods, which leads to price rises for consumers and sparks retaliatory tariffs from other countries that harm exporters and fuel counterproductive trade wars. But if that is all so obvious to everyone, then why is Donald Trump’s administration in the US so determinedly beating a path in the opposite direction? What is Trump thinking?

A profound shift

It is to be hoped that he is in fact thinking, for there is a lot at stake, as that bastion of right-thinking, The Economist, explains. Trump had already raised the average tariff on America’s imports by about twice as much as he did in his first stint in the White House before his “Liberation Day” blitzkrieg. Confidence in the prospects for the American economy had already been “sapped” as a result, and financial markets had swooned. Inflation expectations were edging upwards. Investors were losing faith in the administration’s ability to steer the economy.

And despite the tariffs, which should if all else were equal, have strengthened the currency, the dollar had been sliding, suggesting an “act of grave self-harm” – that the overall “hit” to the US economy from Trump’s policies was more than outweighing the direct impact of rising tariffs. Investors and businesses were unsure how much worse things would get, explaining why surveys were showing an “alarming” fall in planned capital expenditure, foreshadowing slower growth. And then, Trump dropped a further bombshell, jacking up tariffs on all countries and “erecting a wall of protection around the US economy akin to that of the late 1800s”.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Businesses, investors, diplomats and economic forecasters are still trying to think through the details and the consequences. But to get bogged down in the detail risks missing the bigger picture, says Simon Nixon on Substack. Trump’s “Liberation Day” announcement represents the “end of the economic world as we knew it” and the consequences will not be limited to trade. Trump has blown up what was left of the “global rules-based trading system”, and the predictable result will be “chaos”.

America’s average tariff is now estimated to be between 25% and 30%, far above the 20% level it reached in the 1930s following the introduction of the infamous Smoot- Hawley tariffs. Those tariffs, and the retaliation they invited, were sufficiently damaging to lead to a 60% reduction in global trade, deepening the Great Depression and “fuelling what turned into economic and political disaster in Europe”, says Nixon. Trump’s tariffs represent a far larger and more rapid hike, and apply to pretty much everything (the Smoot-Hawley measures were limited to certain goods).

Just how damaging all this will prove to be to global growth is hard to say, not least because it all hinges on how the rest of the world, particularly China and the EU, responds. (China has already announced large retaliatory tariffs.) But few investors realise how closely global trade and capital flows are linked, says Nixon.

If Trump’s tariffs lead to lower cross-border capital flows, that could have huge consequences for the global financial system. Nearly the whole of Wall Street and the City has been “spectacularly wrong-footed” by the scale of all this, and they have “consistently misjudged” Trump’s agenda since his election in November, assuming his tariff threats were all about leverage. The reality is that we are seeing a “profound ideological shift in American economic strategy”. The market turmoil last week was a sign that investors are finally waking up to the reality.

Don’t underestimate Trump

Trump may walk like a buffoon, talk like a buffoon and look like one, as Yanis Varoufakis said in an interview with The Times, but it’s a profound mistake to think that he is one and hence to underestimate him. Trump is surrounded by a serious and intelligent economic team who have very clear ideas about what they are doing.

Which is what? Nothing less than the “controlled disintegration of the world economy by means of a devastating blow”, as Varoufakis explains on Unherd. Despite the outrage about that, it wouldn’t be the first time America has inflicted such a blow. The words just quoted were actually uttered by president Richard Nixon’s treasury secretary, John Connally, who succeeded in convincing Nixon to unleash the famous “Nixon shock” – a series of economic measures including wage and price freezes, tariffs on imports and ending the convertibility of the dollar into gold.

That shock was more devastating than Trump’s, especially for Europeans, but the US didn’t care, says Varoufakis. Its aim was to ensure that “US hegemony grew alongside America’s twin (trade and government) deficits” by seeking an alternative to belt-tightening, which would have risked a recession and curtailed US military might.

The idea was essentially to boost the US trade deficit and make foreign capitalists pay for it, and the result over decades was the construction of the international system of finance, trade and commerce that Trump has just blown up. Connally explained the rationale: “It is tempting to look at the market as an impartial arbiter. But balancing the requirements of a stable international system against the desirability of retaining freedom of action for national policy, a number of countries, including the US, opted for the latter”. Trump has different goals, but the same basic idea.

What are Trump’s goals? Why topple the global trading system that America took such pains to create in the first place and has profited from so handsomely, both economically and in terms of world dominance? There are actually some very good, indeed urgent, reasons, says Juliet Samuel in The Times. For more than a generation, the US economy has been “dragged hideously out of shape by a massive financial distortion” caused by the way investors use the dollar. This has been long been a feature of the world economy, but the US is only now “waking up to the threat” this poses to the country’s industrial base and therefore its security.

In the world financial system, US dollars are used not only by foreigners who want to trade with Americans but by any country that wants to save the proceeds from exports without putting them at risk in their own small or corrupt systems or because they want to avoid moving their own exchange rates. They hoard it instead by buying US Treasury bonds.

When the US was by far the world’s biggest economy, that didn’t affect Americans much. In fact, it gave America “exceptional power to sanction foreigners and to borrow seemingly without limit”. But over decades, and especially since China joined the world trading system, the US economy has become smaller and smaller relative to the rest of the world. This has inflated the value of the dollar to the point where it is “pricing American exporters out of the game”.

As Varoufakis has put it, Trump is trying to correct this by pulling off a tricky balancing act – to weaken the dollar to address this issue, and to rebuild America’s industrial might, while yet retaining the dollar’s global hegemony (his introduction of a cryptocurrency reserve may be another plank in his plan here). The fear is that if nothing had changed, then when US deficits exceeded some threshold, foreigners would have panicked, sold their dollar-denominated assets and found some other currency to hoard. Americans would then have been left “amid international chaos with a wrecked manufacturing sector, derelict financial markets and an insolvent government”.

Tariffs alone are unlikely to work to fix this, but there is, says Samuel, a “grand strategy” at play, outlined by the chairman of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, Stephen Miran, in a paper last year entitled A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. The upshot is that the tariffs are but an “opening salvo in a struggle to fix the US trading position and to sort allies from enemies in doing so”. “Start with tariffs on everyone, let them feel the pain, then offer relief to those willing to help gradually deflate the dollar by slowly selling down Treasuries, opening up their own markets to US goods and agreeing to impose a tariff wall on China.”

The right response

This is, to say the least, a risky and dangerous operation, and lots could go wrong. Indeed, internal opposition to it, even among Republicans in Congress, is starting to take shape. Trump may walk back his tariffs when he gets what he wants from other countries, or under other political or economic pressure. Geopolitical realignments may not work out in the way Trump intends. We simply don’t know what will happen and can’t control what does. All we can control is what we do in response – which should be what?

As a country, the best response may be to sit on our hands. Tariffs mostly hurt the people in the country imposing them, so the rush to impose “retaliatory” tariffs makes no sense, at least not economically, as Julian Jessop points out on CapX. “The best response to someone else doing something stupid… is unlikely to include doing the same stupid thing yourself.”

In fact, Britain should go in the opposite direction and reduce tariffs on imports from the US. Regardless of how Trump responds to that, “British consumers would be better off”. It may not have much impact on the bigger picture, and all major economies will be hurt by a global trade war. But the UK “can at least try” to sit out the war, “rather than rush to join in”.

As the world “hurtles towards mercantilist madness”, the UK should “stride unconditionally and without delay towards the opposite path of enlightenment”, says Harry Phibbs for ConservativeHome. Last year, we “used our Brexit freedoms” to lift tariffs on orange juice, almonds and tofu, among other things. We could go much further, regardless of what others do. “A unilateralist embrace of free trade is in our country’s interest.”

As investors, the key thing is not to rush to action. Assuming you already had a clear idea of your investment goals and a well-balanced portfolio, at times like these “it is usually best to keep a clear head, stick to your investing plan and keep focused on the fact that sharp short-term moves should pale into insignificance over multiple years and decades”, as Rob Morgan, chief analyst for Charles Stanley, points out. “It’s rather like avoiding sea sickness by keeping your eyes on the horizon rather than the rolling waves below.”

If you are investing for the long-term, time spent in the market is far more important than timing the market. Selling out in fear can be the worst thing to do, as large falls can be followed by big rises, so you risk missing out on both sides – selling when prices are depressed and not buying in until they have moved higher. “In the absence of a crystal ball, keeping invested is often the best strategy, no matter how uncomfortable.” Don’t panic, then, but brace for turbulence.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Stuart graduated from the University of Leeds with an honours degree in biochemistry and molecular biology, and from Bath Spa University College with a postgraduate diploma in creative writing.

He started his career in journalism working on newspapers and magazines for the medical profession before joining MoneyWeek shortly after its first issue appeared in November 2000. He has worked for the magazine ever since, and is now the comment editor.

He has long had an interest in political economy and philosophy and writes occasional think pieces on this theme for the magazine, as well as a weekly round up of the best blogs in finance.

His work has appeared in The Lancet and The Idler and in numerous other small-press and online publications.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?

-

What turns a stock market crash into a financial crisis?

What turns a stock market crash into a financial crisis?Opinion Professor Linda Yueh's popular book on major stock market crashes misses key lessons, says Max King

-

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher eraOpinion With the ISA under attack, the Labour government has now started to destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era, returning the economy to the dysfunctional 1970s

-

Why does Trump want Greenland?

Why does Trump want Greenland?The US wants to annex Greenland as it increasingly sees the world in terms of 19th-century Great Power politics and wants to secure crucial national interests