Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

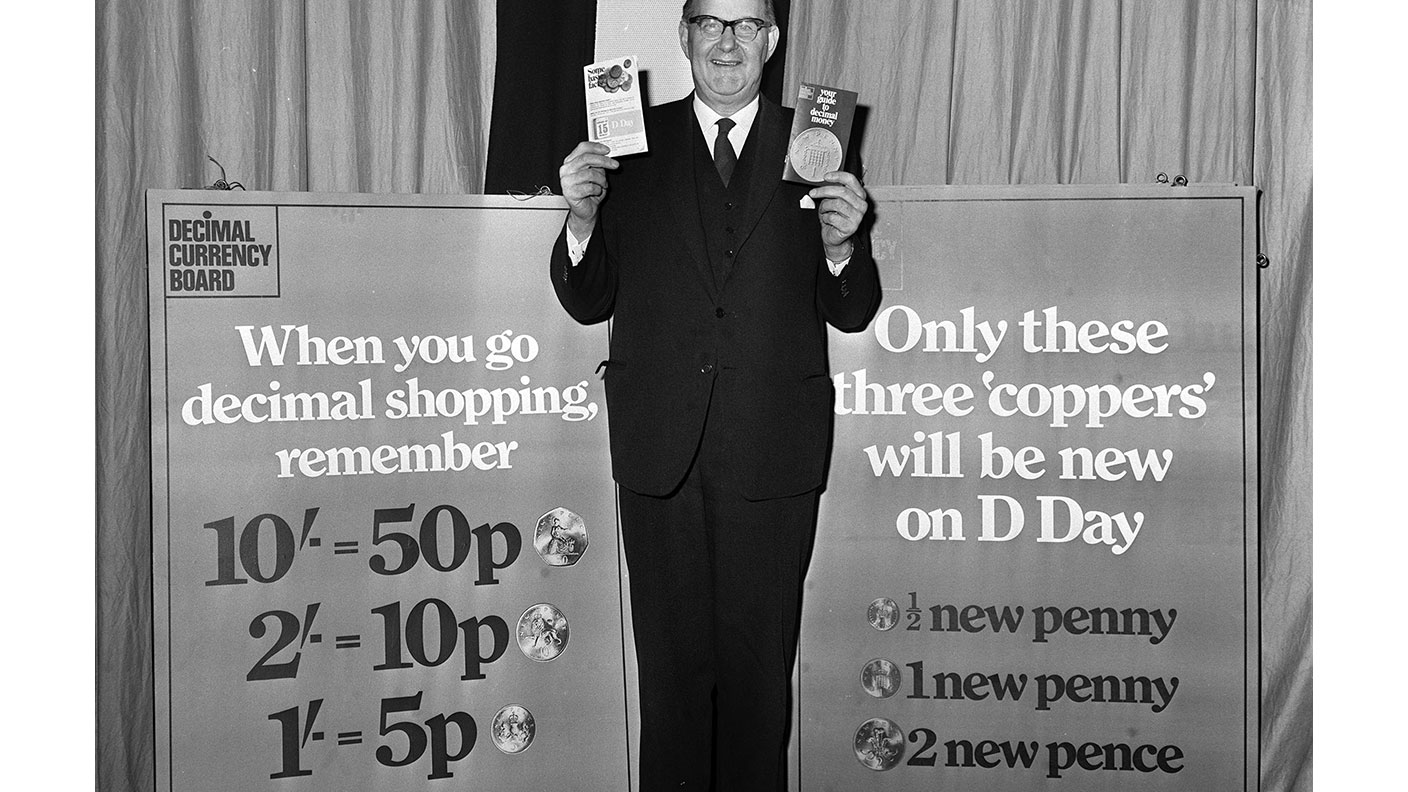

15 February marks the 50th anniversary of the day when, after 150 years of proposals, debate and Royal Commissions, Britain finally adopted a decimal currency. The old system of 12 pennies to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound was replaced by a simple 100 “new pence” to the same old pound. Only a few nostalgic diehards disapproved.

It was widely thought that decimalisation was a precondition of Britain joining what was then called the European Economic Community (EEC) two years later. In fact, decimalisation had been progressing around the world since it was first adopted by the newly formed United States in 1786 and France in 1795. Canada adopted the dollar (a word derived from the central European thaler) upon self-government in 1867.

In 1957, India replaced a rupee divided into 16 annas, each sub-divided into 12 pies, with 100 new pies to the rupee. South Africa followed in 1961 when it adopted the rand, Australia in 1966, New Zealand in 1967 and British colonies when they achieved independence. By 1971, only the UK and Ireland were left. Ireland’s currency was de-facto tied to sterling 50 years after independence – perhaps a lesson for the Scottish nationalists today.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

A Roman legacy

The old currency wasn’t quite as British as it seemed. The abbreviations £, s and d were respectively short for the Latin libra, sestercii and denarii, the coinage of Rome. The lira was the currency of Italy and Turkey, the schilling that of Austria and the pfennig was the German parallel to the penny. The two-shilling coin was known as a florin, the currency of the Netherlands, and the 2s6d or 2/6 coin was “half a crown,” the crown being the unit of currency in Scandinavia. There was no crown coin except for commemorative issues.

The slang word for the sixpence was “a tanner” and for a shilling “a bob”, a word that barely survives in the saying “as bent as a nine bob note”. The “guinea”, or 21 shillings, had been withdrawn in the early 19th century but private doctors, lawyers and auctioneers continued to charge in guineas, probably to squeeze an extra 5% from clients. It survives in the Newmarket races, known as the “1000 guineas” and the “2000 guineas”. The groat, 4d, had disappeared in Victorian times, being unnecessary alongside the 3d coin or “thruppence”. The farthing, remembered in the penny-farthing bicycle, was withdrawn in 1960 and the ha’penny in 1967.

Old coins remained in circulation, as did coins from countries formerly in the sterling area. Late and even mid-Victorian pennies continued to appear in change right up until decimalisation. “Silver” coinage only dated back to the interwar period, when the silver content of the coins was first reduced as the silver content came to be worth more than the denomination, and then replaced by cupro-nickel. The silver thruppence was replaced by a new brass coin, similar in size and shape to the new pound coins, in the late 1930s. The penny, thruppence and half-a-crown were withdrawn at decimalisation, as was the ten-shilling note, to be replaced by ½p, 1p, 2p and 50p coins, but other pre-decimalisation coins remained in circulation. The sixpence disappeared in 1980 but the shilling and florin coins, the same size and of the same value as the new 5p and 10p coins, continued in circulation until 1990. The shilling remains the unit of currency in East Africa.

Stuck in transition

If adoption of a decimal currency was a slow process, full metrification has been even slower, though it has been taught in school maths and science since the early 1970s. The 1985 Weights & Measures Act implemented EEC directives on metrification, but the timetable for full changeover has been repeatedly delayed. So we still use miles and acres rather than kilometres and hectares and many still refer to their height in feet and inches and their weight in stones and pounds. Food and fuel is sold in kilogrammes and litres, but Celsius and Fahrenheit co-exist for temperature. There is little pressure for full metrification, though few people are capable of converting between metric and imperial systems.

The UK is not the only country stuck in transition. The US, the first country to adopt a decimal currency, still uses the imperial system for weights and measures. Recipes use cups and tea/tablespoons as measures, long abandoned even in the UK. Not even in America, though, are microscopic distances referred to as nano or pico-inches. That illustrates a deeper truth: decimalisation and metrification were not pushed through by the EU, politics or modernising social pressures, but by electronic technology. Metric is the only system that pocket calculators, introduced in the early 1970s, or computers understand.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

Do you face ‘double whammy’ inheritance tax blow? How to lessen the impact

Do you face ‘double whammy’ inheritance tax blow? How to lessen the impactFrozen tax thresholds and pensions falling within the scope of inheritance tax will drag thousands more estates into losing their residence nil-rate band, analysis suggests

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive

-

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growth

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growthGDP doesn’t measure what we should care about, say critics. Is that true?

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?