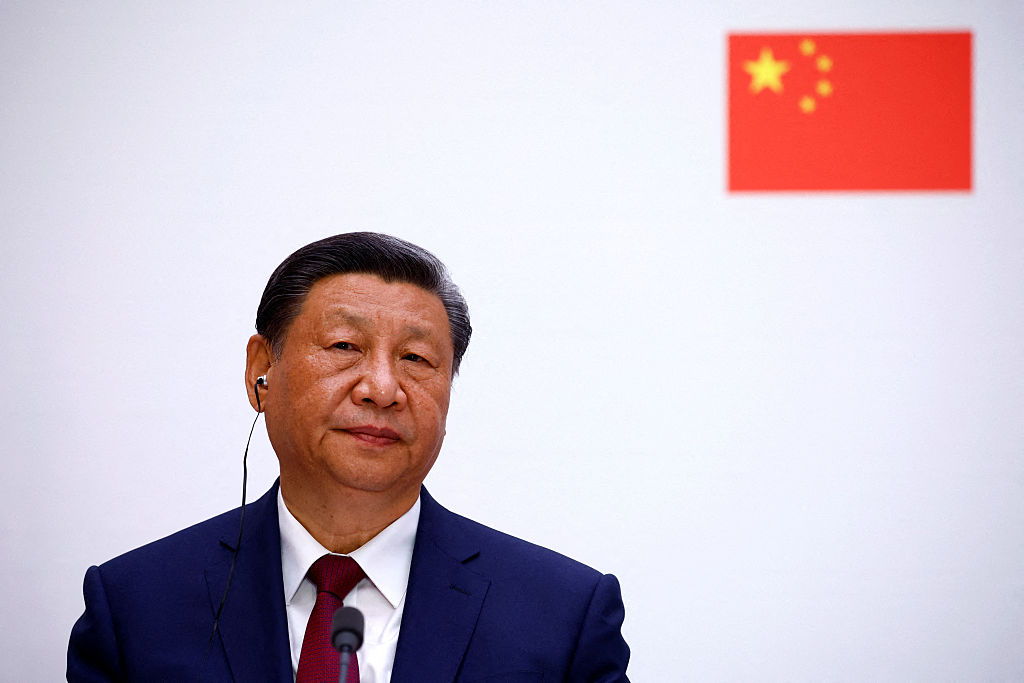

Xi Jinping masters “The Art of the Stall”

China’s Xi Jinping appears to have played his hand well in the face of hostility and threats from Donald Trump. But at home, his position may not be as secure as it seems.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

If Xi Jinping wrote a book about dealing with Donald Trump, it would probably focus on “exploiting the US president’s greatest weaknesses” – and then “using the time gained” to strengthen China’s position, says The New York Times. “The Art of the Stall” appears to have been Beijing’s strategy. Rather than yield to tariff threats, China played the “trump card” of its control of critical minerals, while kicking thornier disputes deep into the long grass of “framework” talks. As an exercise in cunning, it cannot be faulted.

The irony, says The Spectator, is that even as Xi basks in the admiration of Western strategists, his position at home is looking ever less secure. Two years ago, the dictatorial Communist Party leader “presumptuously declared his intention to rule until 2032”. Plenty of people are now prepared to bet against that outcome. Reading the runes of what is going on in the opaque world of Chinese politics is always difficult, but of late, China-watchers have “detected subtle changes”.

In the last two weeks of May, Xi seemingly disappeared from public view – and his once ubiquitous presence on the front cover of the “People’s Liberation Army Daily” has become much patchier. His power base also appears under threat. Prominent members of Xi’s “Fujian faction” – including the vice-chair of the Central Military Commission and a senior admiral – have been arrested or investigated, while “other Xi generals have been removed from their posts”. A 40-episode drama series, Time in the Northwest, was dropped by China’s main state broadcaster after just two episodes. The piece was “an unashamed glorification” of Xi’s family – in particular his father, Xi Zhongxun. A revolutionary who rose to power under Mao before being purged in the Cultural Revolution, he was rehabilitated under the reformist Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Unshakeable loyalty

Few people have shaped Xi, who was born in 1953, as much as his father, says The Economist. Which is why a new biography of Xi Zhongxun by the American scholar Joseph Torigian conveys such fascinating, and sometimes gruesome, insights. In The Party’s Interests Come First, Torigian shows that, throughout his life, “Xi has been loyal to two groups that demand absolute obedience: the party and the family”. Both were often strict, yet that never dented his loyalty. As a boy, Xi washed in his father’s bathwater and practised deference at every turn, having been taught that “children who did not respect their parents were doomed to fail as adults”. Even when Xi was in his mid-30s and a rising star in the party, the ordeals continued. Torigian relates how Xi Zhongxun – then in his 70s with rotten teeth – “extracted some half-masticated garlic ribs from his mouth and gave them to his son to finish”. Xi accepted “without hesitation or complaint”.

After the hardships the family had endured during the Cultural Revolution, this probably seemed tame. When Xi Zhongxun was kidnapped, held in solitary confinement and tortured, his family was forced to denounce him. One daughter committed suicide, while the teenaged Xi was branded a traitor and forced to wear a heavy steel cap in front of a baying crowd. “His mother joined in the jeering.” Shortly after, Xi was “sent down” to a desolate part of the country, where he lived in a cave.

Xi’s rise began when his father became governor of Guangdong province, a “Special Economic Zone”, under Deng. But expectations that he would become an economic reformer proved premature. “His experience of injustice has not taught him that arbitrary power is undesirable; only that it should be wielded less chaotically than it was under Mao, by someone wise like himself,” says The Economist.

Might his time be up? Similar rumours have circulated before and come to nothing, says The Spectator. But given “the dire problems facing China” and the “indifferent performance” of its autocratic leader, it’s quite plausible that “CCP elders are casting around” for a more liberal successor. “If so, the consequences for Taiwan, and US-China relations, could be dramatic – and possibly beneficial to both.”

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example