Mohammed bin Salman: The new face of Saudi Arabia

Under the crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia's de facto ruler, the kingdom has pursued ambitious reforms to transform itself into a thriving 21st-century economy

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Has the country really changed?

Yes, in important ways, Saudi Arabia has changed radically in the ten years since King Salman ascended the throne aged 79, and his son, Mohammed bin Salman (who is known as MBS), became the country’s de facto ruler (as crown prince from 2017 onwards). Ten years ago, women were still shut out of the labour market and public life, prohibited from driving or even leaving the house without a male guardian. Today, they are free to work and travel where they like. Many have ditched the burqa for a simple headscarf. The religious police and “vice squad”, once a ubiquitous presence, have disappeared. Schools have slashed the amount of time devoted to religious instruction. What was once a closed and repressive society has opened up in myriad ways and become far more akin to other Gulf and Middle Eastern states.

So it’s become a democracy?

Hardly. Saudi Arabia remains an autocracy, where a super-privileged elite holds power and the crown prince does not brook dissent. But the country no longer sponsors and exports jihadist terrorism and is a “force for order” and a “stabilising influence in the Middle East”, says The Economist. It counsels restraint on the conflict in Yemen. It is open to better relations with both Iran and Israel, and has helped Syria’s new government by paying some of its debts. If not exactly an enlightened despot, MBS – still aged just 39, and poised to become king for decades – is at least a sane and increasingly pragmatic one.

What about Saudi Arabia's economy?

MBS’s stated mission, under his Vision 2030 rubric, is to transform Saudi Arabia from a petro-state into a diversified 21st-century economy with a flourishing private sector – readying it for the day when the oil runs dry. The hard truth is that while a start has been made, there is much left to do. Oil’s share of the economy remains high, too, although it has fallen from 36% of GDP in 2016 to 26% last year, according to official figures. However, other estimates put the share rather higher than this. And once all economic activity related to oil and gas extraction is factored in, almost half the Saudi economy (48%) is hydrocarbon-dependent, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). And oil still accounts for between 60% and 75% of government revenues, meaning the House of Saud’s fragile social contract is still underwritten by the nation’s oilfields.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So the oil price is a worry?

According to projections by the International Monetary Fund, Saudi Arabia needs the global oil price to be more than $90 a barrel in order to balance its budget. Prices are currently a little above $60, and are not expected to rise much this year. Goldman Sachs has lowered its year-end 2025 oil price forecast to $60 a barrel for Brent crude, and $56 next year. If prices were to stay around $62 this year, Saudi Arabia’s 2024 budget deficit of $30.8 billion would more than double to around $70 billion - $75 billion, according to the bank’s Middle East economist Farouk Soussa. “That means more borrowing, probably means more cutbacks on expenditure, it probably means more selling of assets, or all of the above, and this is going to have an impact both on domestic financial conditions and potentially even international ones.”

What about debt?

The lower oil price is a worry, but it’s not about to precipitate a debt crisis. At the end of last year, Saudi’s debt-to-GDP ratio was just under 30% – modest compared with the likes of the US (124%) or France (111%). Riyadh still has significant headroom for borrowing. Yet $75 billion in debt issuance would be hard for the market to absorb, and the Saudis will need to look at other solutions. In terms of cutting expenditure, many regional economists believe that some of the flashier projects, such as the vast, futuristic “linear city” Neom, will be further scaled back. Other such projects, estimated to cost nearly $900 billion by 2030, include 50 luxury hotels strung along the Red Sea, a ski resort in the desert, and the world’s biggest building in Riyadh. There’s also the possibility of selling more domestic assets, including stakes in the state-owned companies Saudi Aramco and Sabic.

What sectors are thriving in Saudi Arabia?

Perhaps more important than such projects are the “government’s efforts to foster new industries, from tourism to carmaking”, says The Economist. Meanwhile, civil servants are rewriting rules on everything from divorce to foreign investment, with more than 600 packages of reforms in the works. A liberalisation of mortgage lending means that construction is booming. Retail and hospitality are growing fast, as is tourism, which has jumped from around 60 million overnight stays in 2016 to more than 100 million in 2023 (the bulk of this being domestic tourism). Yet the Saudi economy remains a textbook case of “crowding out”, where the state’s dominance of key sectors has stifled private investment and enterprise. About half the male labour force work as civil servants, and political connections remain vital to doing business.

What does the future hold?

One ambition is to establish strength in artificial intelligence (AI) and data centres. Saudi’s new state-owned AI company Humain has signed deals worth $23 billion with US tech groups including Nvidia, AMD, Amazon Web Services and Qualcomm, according to its chief executive. And it has launched a $10 billion venture-capital fund as it leads the kingdom’s effort to become a global AI hub. It’s currently in talks with US groups, including OpenAI, Elon Musk’s xAI and Andreessen Horowitz about its plans. But allied to these lofty ambitions are more prosaic goals – improving the country’s education system; attracting the expertise needed to boost emerging sectors, including carmaking, semiconductors and renewable energy. Social liberalisation may have bought the regime some time in terms of pushing through economic reforms. But those reforms are just getting started.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

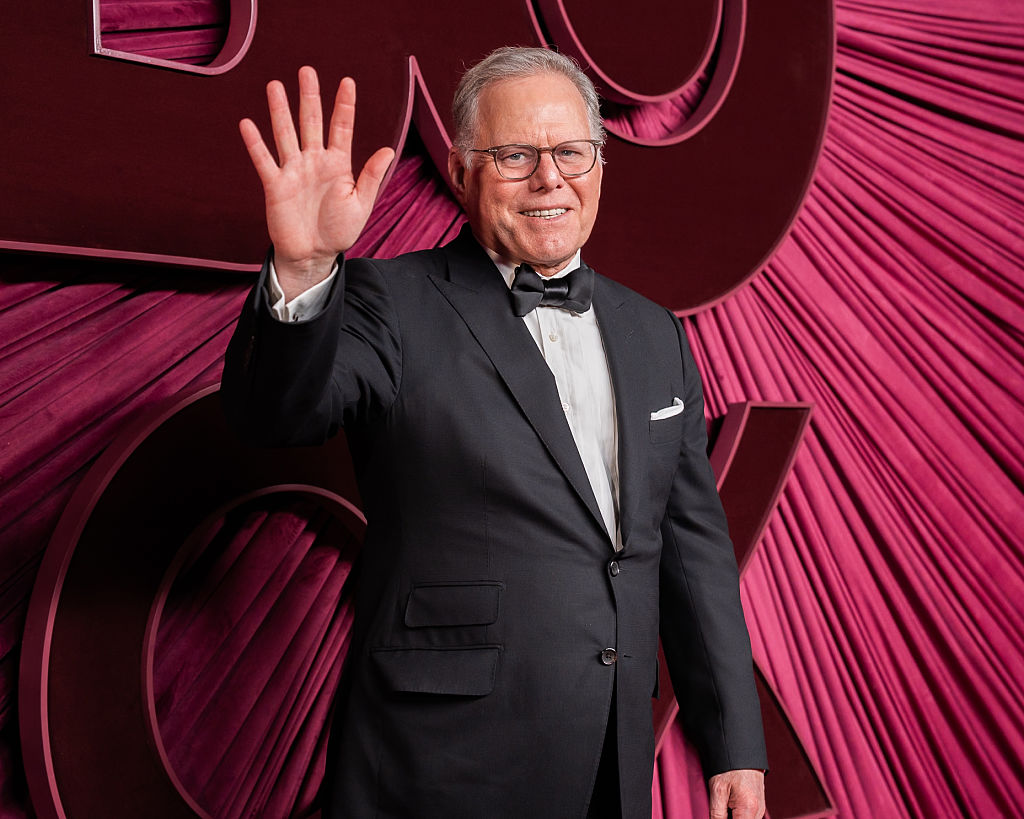

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off