Henry Keswick: the plutocrat who fell for China

Henry Keswick, a scion of the Jardine Matheson trading company, rebuilt the firm's fortunes after the upheavals of the 1990s. He died aged 86.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

In 2014, Henry Keswick wrote to the Financial Times to voice his opposition to Scottish independence. “I am a humble Scottish merchant trading in the China Seas. My family has followed this profession for almost 200 years,” he wrote. “When we are bearing the sticky heat of China’s Pearl River Delta or the tropical rainforests of equatorial Borneo, we dream about the cool, soft mist of the green Galloway hills where we were bred.”

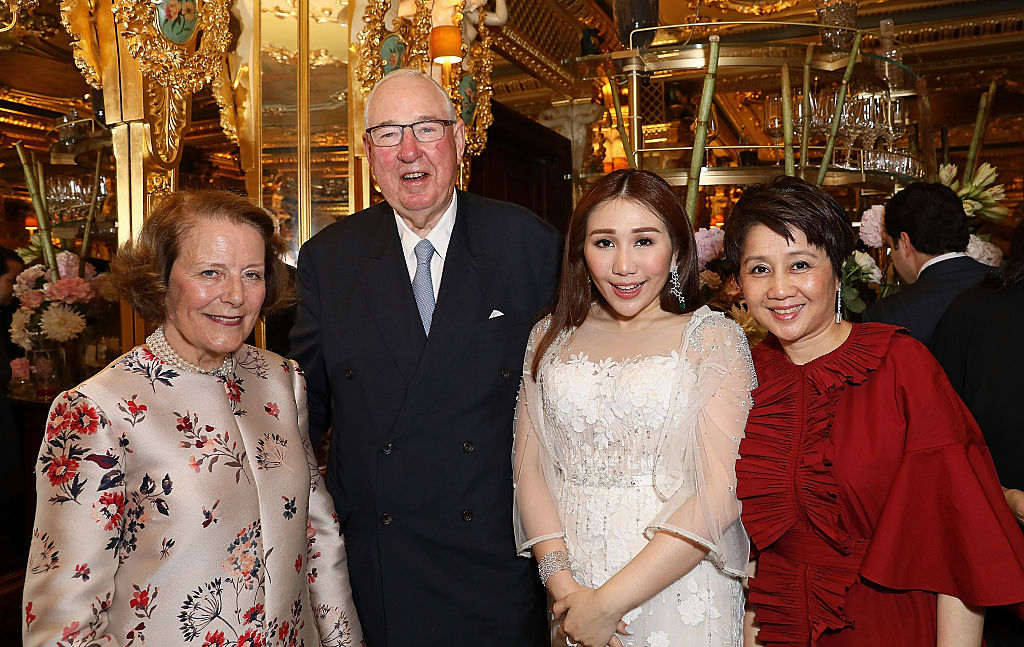

Keswick, who has died aged 86, was “an almost extinct type”, says Charles Moore in The Spectator: “the patrician plutocrat – grand, usually benevolent, occasionally autocratic”. As a scion of the Jardine Matheson trading company – co-founded in 1832 in Canton (now known as Guangzhou, China) by a Jardine forebear to trade tea, silk, rhubarb and opium – he became the Hong Kong firm’s youthful “taipan” (leader) in 1970, and “therefore rich”.

Five years later, aged 36, he returned to Britain, “almost like Clive of India”, seeking a “country house, a wife and a seat in parliament”. The latter ambition went awry when, shortlisted for a Conservative seat in Wiltshire, he was asked if he’d buy a house in the constituency. “Madam,” he replied, “my arboretum is in the constituency… If you insist, I shall buy a house in every village in the constituency.”

Henry Keswick's legacy

“Tall, portly with a formidable appetite for Scotch eggs”, Keswick’s grand air belied a keen business brain, says The Times. Credited by the FT as the “taipan who took Jardine Matheson back to China” after the upheavals of the 1990s, he also pushed the trading house into new southeast Asian markets. By 2017, Astra International, an Indonesian automotive and industrial group, was delivering 25% of the group’s profits. Keswick “took the performance of the US investor Warren Buffett as his benchmark” – and gave the sage a run for his money. Jardine’s net assets grew from $70m to $26bn between 1972 and 2017.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Nonetheless, he had his critics, says The Telegraph. Not every hefty diversification bet paid off, and he and his brother Simon acquired a reputation for “buying high and selling low”. Still, Jardine’s “core businesses carried them through”. Keswick was admired (“grudgingly by some investors”) for his “tenacity in maintaining control of the group” through “complex voting rights and cross-shareholdings”.

Born in Shanghai in 1938, Henry Neville Lindley Keswick grew up in turbulent times. The family fled Shanghai to escape Japanese occupation in 1942 and returned after the war only to be expelled during the communist takeover of 1949 when Jardine’s then substantial property, railway and business assets were seized.

Regrouping in Hong Kong, Jardine’s “embedded itself into the fabric of the British colony”, says the FT. By the time he returned to Hong Kong in the early 1960s, Jardine’s had “recovered handsomely” and boomed during Hong Kong’s “period of rapid expansion” in the 1970s, says The Telegraph. Keswick, “rarely seen without a large cigar”, ran the business with a “commanding” style that won “the respect – if not necessarily the affection – of the colony’s leading Chinese entrepreneurs”.

Keswick never hid his distaste for communism and, in the run-up to Hong Kong’s 1997 handover to China, moved Jardine’s listing from Hong Kong to Singapore. He spent the next 30 years “mending fences with Beijing while hedging his bets”, says The Times. While enjoying a comfortable life in Britain – where Keswick owned the Oare estate in Wiltshire and two Scottish sporting estates – the Far East never lost its pull. “Mr Keswick you were bitten by the snake,” a senior Chinese leader once observed. “You waited, you watched, but you came back!”

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

Last chance to invest in VCTs? Here's what you need to know

Last chance to invest in VCTs? Here's what you need to knowInvestors have pumped millions more into Venture Capital Trusts (VCTS) so far this tax year, but time is running out to take advantage of tax perks from them.

-

ISA quiz: How much do you know about the tax wrapper?

ISA quiz: How much do you know about the tax wrapper?Quiz One of the most efficient ways to keep your savings or investments free from tax is by putting them in an Individual Savings Account (ISA). How much do you know about ISAs?

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

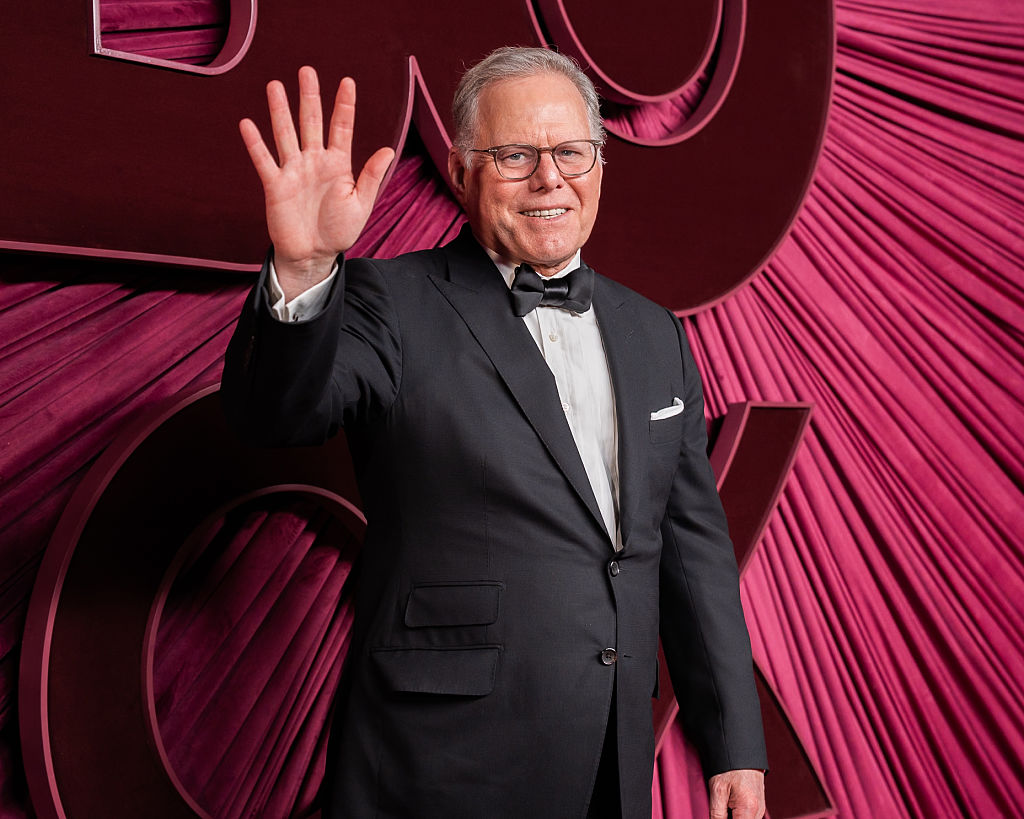

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off