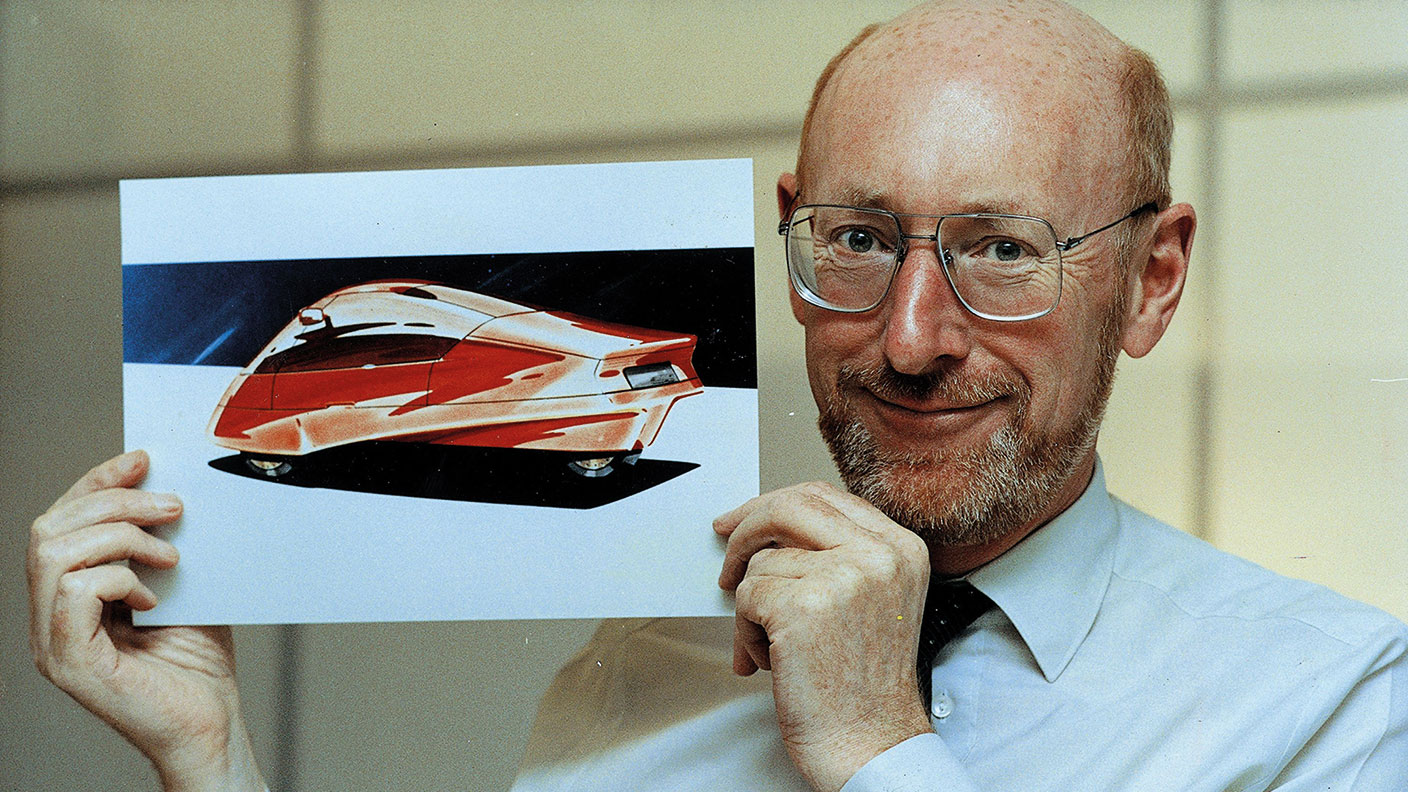

Clive Sinclair: the father of the home computer

Clive Sinclair was a serial inventor and visionary whose output also included the prototype electric car. His other interests included poetry, marathon-running and poker.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“RIP, Sir Sinclair. I loved that computer,” tweeted Elon Musk. He wasn’t alone, says the Financial Times. The death, aged 81, of Sir Clive Sinclair, the entrepreneur behind the UK’s first mass-market home computer, brought tributes from “a host of engineers, entrepreneurs and tech billionaires” who claimed “their careers had been built on his inventions” – notably the affordable ZX Spectrum.

Coming a cropper

“One part visionary, one part dotty uncle and one part marketing genius”, for a few years in the 1980s Sinclair epitomised “the new hi-tech, go-ahead Britain”, says The Guardian. But his reputation “came a cropper” in 1985 with the launch of the C5, his prototype electric car. The three-wheeled, low-slung vehicle had a top-speed of 15mph and a battery that needed recharging every 20 miles.

Sinclair predicted annual sales of 100,000, but the “tricycle with a modified Hoover washing-machine engine” sank “under gales of derisive media laughter”. Several ensuing inventions – including an electric bicycle called a Zike and a tiny radio that could fit in the ear – did little to dispel his eccentric image. But his descent into mad-professor territory never deterred him, says The Independent on Sunday. “If an idea is good enough, it’s going to appear pretty crazy to almost anyone,” he observed. “Either you do it yourself or it ain’t going to happen.”

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Born in 1940, in the London suburb of Richmond, Sinclair was “the son and grandson of engineers”, says The Guardian. His own enthusiasm was apparently sparked by an inventor character on the children’s radio programme Toytown. By the age of 12, “he had designed a one-person submarine out of a petrol tank”.

Leaving school with A-Levels in maths and physics, Sinclair eschewed university to become a journalist on the trade paper Practical Wireless. His passion was “miniaturisation” and in 1962 he and his first wife, Ann, formed a company, Sinclair Radionics, making mail-order radio kits “using transistors bought cheaply... and dispatched to customers” from their home.

The combustible calculator

Sinclair’s drive for innovation saw him produce what he claimed to be the world’s first pocket calculator in 1973, says The Daily Telegraph. Its tendency to burst into flames nearly caused “an international incident”: when a Soviet diplomat’s device exploded in London, the Russians thought it was “an assassination attempt”.

Sinclair’s own temperament was no less explosive. Reportedly “he only went into computing to annoy his ex-employee, Chris Curry, who left Sinclair Research to develop home computers and founded the successful Acorn brand”. Indeed, Sinclair prided himself on never using computers.

Sinclair’s rivalry with Curry may be one reason he took his eye off the commercial ball. By the mid-1980s, the Spectrum had been eclipsed by its rival Amstrad and a new generation of IBM PCs and clones. He consoled himself with other interests, including poetry, marathon-running and poker.

Memories of the Sinclair C5

By Dr Michael Tubbs

The newspapers have been full of pictures of Sinclair’s C5 car, but he should really be remembered for bringing affordable computers such as the ZX Spectrum into British homes.

I remember receiving a call from a headhunter when I was running the product R&D at Lucas, which was then the UK’s largest supplier of automotive and aerospace components and systems. I had R&D projects on electric vehicles and new batteries at Lucas, so I was not surprised when the headhunter told me that he had an exciting new position to fill as technical director of a very well-funded new electric vehicle company. He mentioned a salary of twice what Lucas were paying me, so I went along to an interview with the managing director.

He described the company and explained that they wanted to launch a new electric car. I asked him how he believed he could solve the problem of a worthwhile range and performance with a battery of the size and weight that could be fitted in a small car. He replied that he had a solution but could not even outline it to me until I had accepted the job. Of course, he did not have a solution as I realised a little later. I replied that I needed an answer before I could consider accepting an offer so, since neither of us would budge, I left.

Some weeks later I opened my copy of The Sunday Times and saw a picture on the front page of the man who had accepted the job I had refused, and he was seated in a Sinclair C5 that looked like a white bathtub driving round Hyde Park corner with a double-decker London bus towering over him. I thought “rather you than me”. He drew the large technical director’s salary for only a few more weeks – production was cut by 90% just three months after launch, and ceased soon after that.

With an IQ of 159, he became chair of the British arm of Mensa. At 70, he married a former pole-dancer 36 years his junior. Sinclair long ago secured his legacy as “the father of the home computer”, says The Conversation. “But time is only now vindicating his other creations” – particularly “electrified personal transportation”. Even his so-called failures were prescient.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off