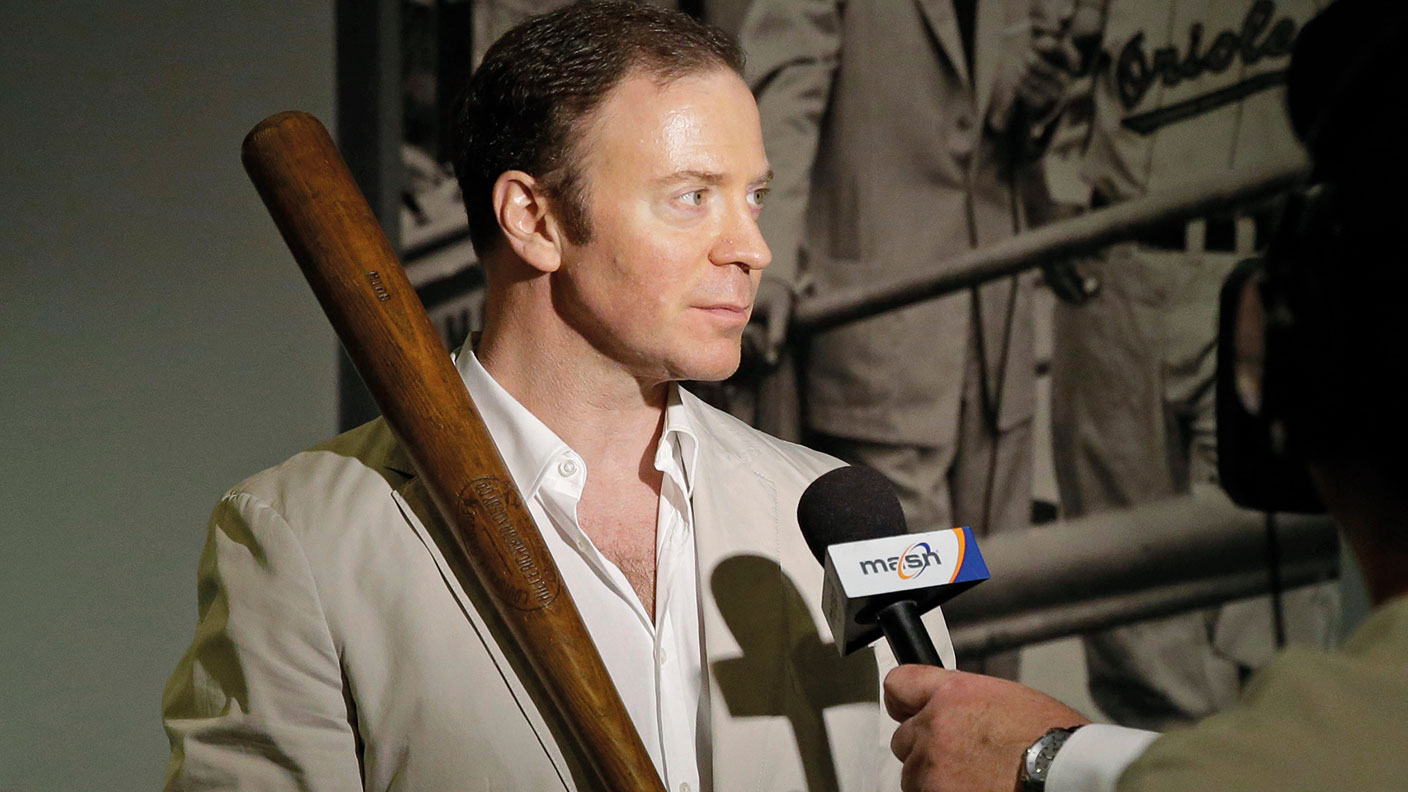

Ken Goldin: making a million from a child’s hobby

Ken Goldin’s career began when, aged 12, he swapped his toy cars for a baseball-card collection. He turned the hobby into a multimillion-dollar business – and now the market is going wild.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Ken Goldin has been selling sports trading cards and other memorabilia for four decades and his company, Goldin Auctions, is known by some as “the Sotheby’s of sports”. But even he has been taken aback by the sector’s red-hot boom this year. “There’s never been a time like this in the history of the business,” he told CNN Business in February, shortly after a card of basketball star Michael Jordan, as a rookie player, sold for a record $738,000, having more than tripled in price in a matter of weeks. Since then, things have become even crazier. Goldin reckons his “little company running on 2002 software” is on course to make $500m in sales this year. “I would bet that for every person who wanted a Jordan rookie card in 2019, there’s 100 [now].”

Rummaging around in the loft

The trading-card renaissance has its roots in the pandemic. “Stuck at home without live sports games, people began raiding their attics and basements and digging up old cards,” says CNN. Many had been children during the last big craze in the 1980s. Celebrities got in on the act and then things just mushroomed. The same “speculative forces” that sent prices of cryptocurrencies, meme stocks, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), music rights and other alternatives assets through the roof homed in on cards. “For the first time in his career, Goldin has been fielding calls from hedge funds.” In February, he sold a majority stake in his firm to LA-based investment firm Chernin.

A new career beckons, says Bloomberg. Goldin, 55, is already one of the most recognisable faces of the sports collectables industry – a regular on news shows and the like. Now, having been approached by a well-known producer in the field, the New York-born impresario is “getting the reality-TV treatment”. Goldin, an “outsized personality”, seems tailor-made for the role.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The “Babe Ruth of sports memorabilia” got into card-collecting early, says NJ.com. Goldin can trace his empire back to 1978 when, as a 12-year-old, he “fleeced a buddy out of his baseball-card collection” by swapping it for $50 worth of miniature racing cars. He insists neither of them knew the value of what they were trading. Goldin’s father, an executive in a medical equipment company, caught the bug and together they went to a flea market and bought “six or seven trash bags filled with cards – 70,000 in all”, says Bloomberg. Goldin spent months sorting them, keeping the best to sell on.

Floating on Nasdaq

By the mid-1980s, the hobby had evolved into a business, Score Board, says fundinguniverse.com. Riding the coat-tails of the 1980s memorabilia boom, it enjoyed an extraordinary trajectory – becoming the first of its kind to float on Nasdaq in 1987. The Goldins branched out into “exclusive autograph contracts” – getting baseball legends such as Mickey Mantle and Joe DiMaggio on their roster – and later moved into entertainment memorabilia, signing contracts with Elvis Presley Enterprises and Paramount. At its peak in 1994, Score Board made $100m in sales. But the death of Goldin’s father that year coincided with an industry downturn. Goldin left the company in 1997; the following year it went bankrupt.

Is he concerned that history will repeat itself? Not a bit of it, says CNN. Prices might fluctuate, but, however wild the market, Goldin reckons something has shifted. “The difference between cards and stock [is] nobody loves a stock,” he says. Asking an avid card collector to sell “is like getting them to take off an arm”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off