Philip Day: the retail knight falls off his horse

Retail baron Philip Day, once seen as the saviour of the British high street, is under fire for holding to a monastic silence as his suppliers struggle due to coronavirus.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

In recent years, the billionaire proprietor of Edinburgh Woollen Mill, Philip Day, has basked in the glow of a burgeoning reputation as a saviour of the British high street. “The opposite” of the sector’s stereotypical “brash entrepreneur”, Day is “quietly showing his retail rivals the way”, said The Guardian in 2018. Having quietly built a 1,113-store powerhouse from formerly stricken fashion chains such as Jaeger, Austin Reed, Peacocks and Bonmarché, his star is in the ascendant even as the curtain falls on Sir Philip Green’s troubled Arcadia empire. “As one billionaire Philip fades into the background another is hoving into view.”

From council estate to castle

Eighteen months and a pandemic later, a new, rather less flattering picture of the Lancashire-born tycoon’s operation is emerging. As it battles the current “brutal” economic environment, Edinburgh Woollen Mill is alleged to have resorted to tactics that “are pushing suppliers both at home and overseas to the brink” – notably, refusing to honour orders, says Sam Chambers in The Sunday Times. Partners claim their “pleas for help” have been met with what one called “monastic silence”, raising questions over the health of Day’s empire.

Day keeps a low profile. But he has certainly come a long way from his childhood roots on a Stockport council estate. These days, notes The Independent, he “owns a castle in Carlisle”, but “officially lives in Switzerland and spends a lot of his time in Dubai”, where his acquisition company, Spectre, is registered. “He reportedly bought his first helicopter from Sports Direct tycoon Mike Ashley.”

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Born in 1965, Day once observed that on leaving school (having reportedly turned down a place at university) he saw three career options, says The Sunday Times: “the mines, the army, or industry”. Choosing the latter, he joined textiles giant Coats Viyella, which gave him a useful insight into how the fashion supply chain worked. At 28, he was headhunted by the upmarket clothing brand,Aquascutum, rising to become joint managing director within five years, says The Guardian. Then, in 2001, he seized his chance to build his own retail entity. Teaming up with private-equity firm Rutland Partners, he bought the Edinburgh Woollen Mill chain for £55m and succeeded in transforming “one of the fustiest brands on the high street” into a mecca for tourists, who snapped up its tartan scarves, shortbread and Scottish knits – no matter that many of them had actually been made in Mongolia.

A taste for scavenging

Over the past decade, Day – who paid himself a £16m dividend last year – has developed “a taste for scavenging”, snapping up ailing chains from administration. Critics accuse him of asset-stripping and using “financial engineering” to turn a profit from failing brands while using insolvency laws to his advantage, says The Independent. Most recently, his takeover of Bonmarché raised eyebrows. Just months after being acquired by Day in “an unusual takeover battle” last summer, the struggling womenswear retailer called in the administrators, blaming “Brexit uncertainty” for some of its woes, says the FT. The pandemic is posing similar challenges for the man once described as “the knight in a comfy cardie”. We may soon get a better idea of how close to reality that cosy image really is.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

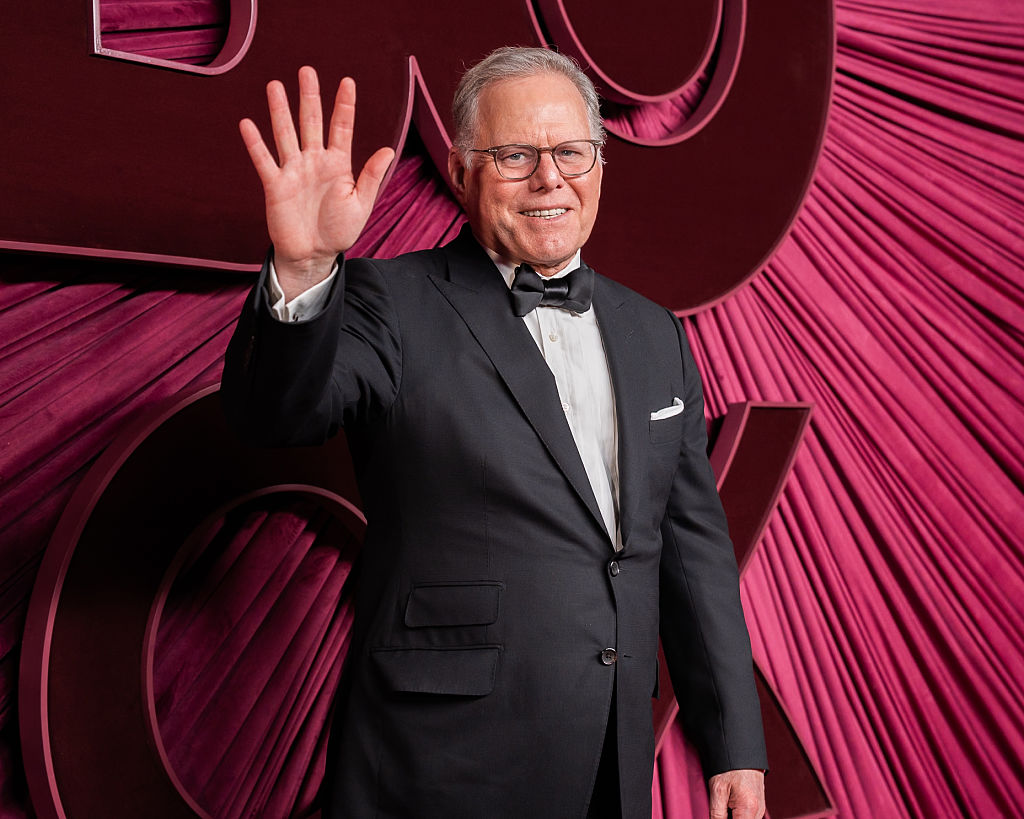

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off