Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

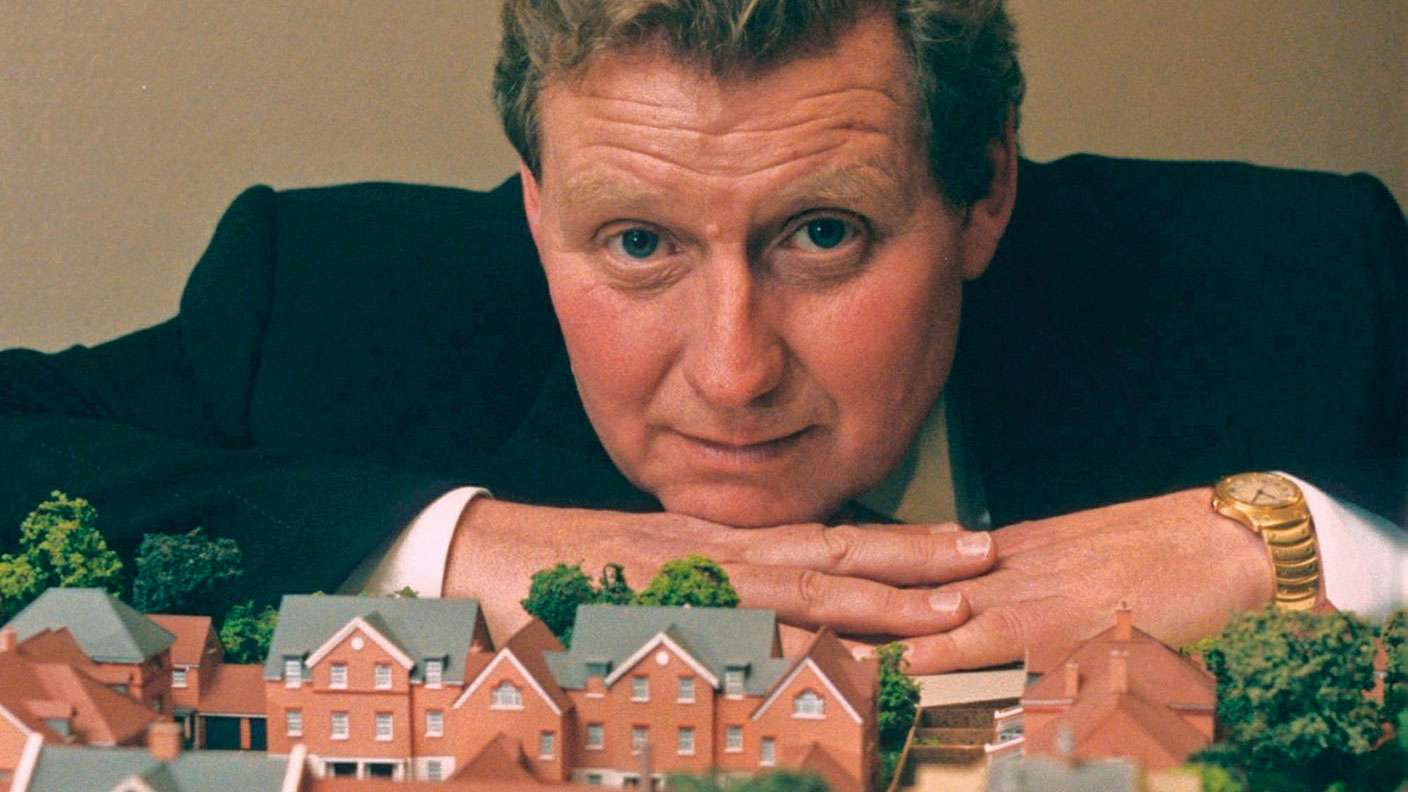

I always enjoyed company visits as a fund manager. They were a valuable reminder that I was investing in businesses rather than bits of paper and an opportunity to gain insights. Occasionally they were a priceless crash-course in getting to know a company, an industry and how a business should be run. One of those was a trip to Epsom in the early 1990s to see Berkeley Homes, the housebuilder co-founded by Tony Pidgley, who sadly died recently.

Berkeley was then a small company specialising in upmarket houses. Pidgley, a Barnardo’s boy who left school at 15, had started his housing career at Crest Nicholson. He told us that in the 1970s housing slump he had been sent to Kent as their star salesman to shift a new development of 12 houses, only one of which had been sold. In a fortnight, he had sold them all. But over the next few weeks, all but one of the sales fell through. The lesson, he said, was that in one of the sector’s periodic slumps, there is nothing you can do.

He applied that lesson several times at Berkeley, cashing up the company and battening down the hatches when the market was riding high. He was happy to acquire construction plots under option, foregoing the planning gain for the reduced risk and capital commitment.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

A new approach

At the time, standard housebuilders’ practice was to buy a plot of land, usually greenfield, flatten it, build near-identical houses on it then offer them for sale. Buyers would have to wait at least ten years for the saplings and landscaping to mature and new-build housing had a poor reputation among the well-to-do.

Pidgley’s formula was radically different. Berkeley built on small sites, typically buying an old, dysfunctional house with too much land, knocking it down and building three to five houses on the site. This spared the Green Belt and meant that road and utility infrastructure was already on the site.

Rather than flatten the site, Berkeley left mature trees and landscape features alone, to the inconvenience of the contractors. The houses were sold off-plan, reducing the financial risk but enabling the buyers to decide the model of the house and specify features. Double-glazing was standard and the customer chose the decoration and fittings.

Everything from extra electrical sockets to conservatories and swimming pools could be added at a fraction of the cost of doing it yourself. All the houses were different and our personal prejudices against new-build properties were swept aside.

On the Epsom trip, Pidgley offered to show us a house that was completed and sold, inviting us to pick one at random on a development. We trooped up to the door, Pidgley pressed the bell and we all expected to be sent packing.

When a lady opened the door, Pidgley introduced himself and pointed to some paving which he said was uneven. “I’ll send the boys round tomorrow to sort it out,” he said. Within a few minutes, the lady was giving us a tour of the house and then offered us tea and biscuits while answering questions from half a dozen complete strangers in her sitting room.

Gazumped by dad

Tony Pidgley junior had recently joined the business, but he wasn’t going to be given an easy time (he had just written off an expensive new car). He went on to found his own company and be successful in his own right, sometimes despite his father. A popular story has his father asking him at a family Sunday lunch how business was. His son then told him about a fantastic development opportunity he had found.

A month later, his father asked him how he was getting on with that deal. His son, crestfallen, said he had been gazumped by an unknown rival, to which his father said “Son, the first rule of business is that you don’t brag about the deal until the papers are signed”. Berkeley was the gazumper.

Berkeley, through its St George and St James subsidiaries, later moved heavily into urban regeneration. Anyone who remembers the sites at Woodberry Down, Woolwich Arsenal and Kidbrooke (arguably London’s worst sink-estate) before development can only be staggered at the transformation. Friends who have been involved in such projects with Berkeley say that they never offered the best deal financially, but more than made up for it in reliability and quality.

In his book Home Truths Liam Halligan is scathing about housebuilders generally, but has nothing but praise for Pidgley. He tells the story about how Pidgley bought a site near Effingham Junction “for a song – about £3m” because planning permission was thought to be impossible.

Pidgley realised that a nearby school needed redevelopment and offered £25m towards it, plus 20% affordable housing. The offer was increased to £32m and approved by the secretary of state. Berkeley built 295 new houses and still made a profit margin of 20%.

Pidgley was a genius who transformed the housebuilding industry, revived run-down urban areas and made great returns for his investors. His focus was always on building, not on trading land, and on deals that shared the benefit between his customers, the public and his investors. His legacy is immortal.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

The downfall of Peter Mandelson

The downfall of Peter MandelsonPeter Mandelson is used to penning resignation statements, but his latest might well be his last. He might even face time in prison.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

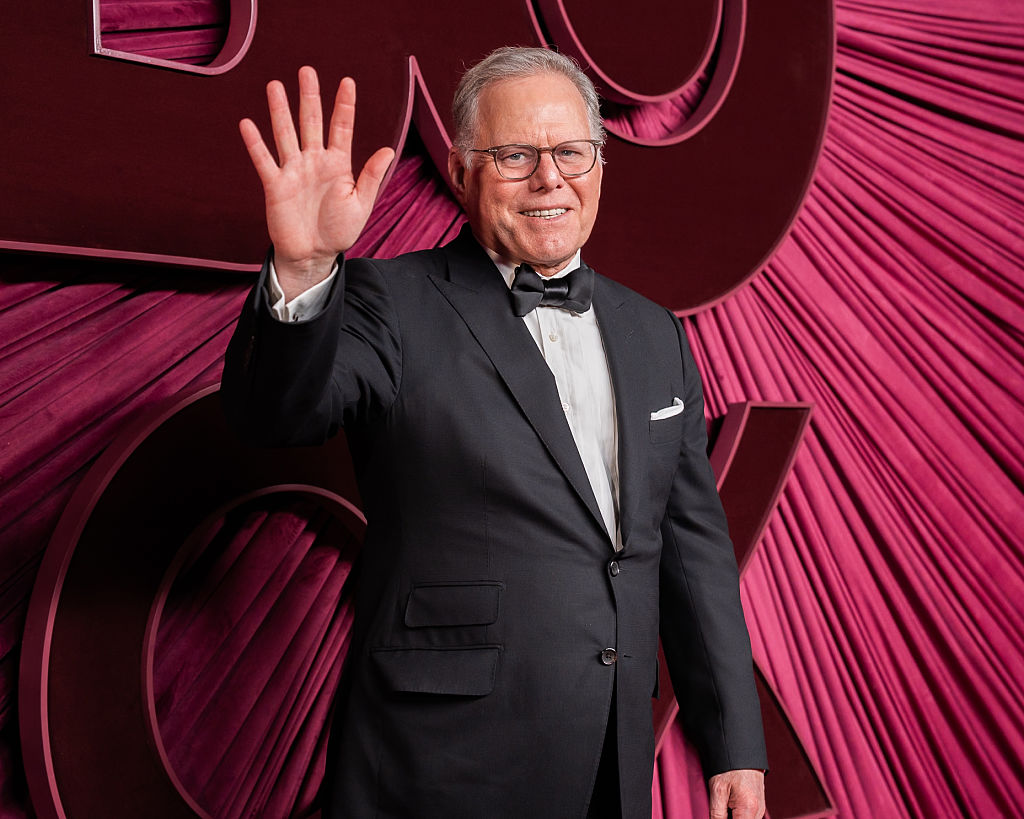

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi