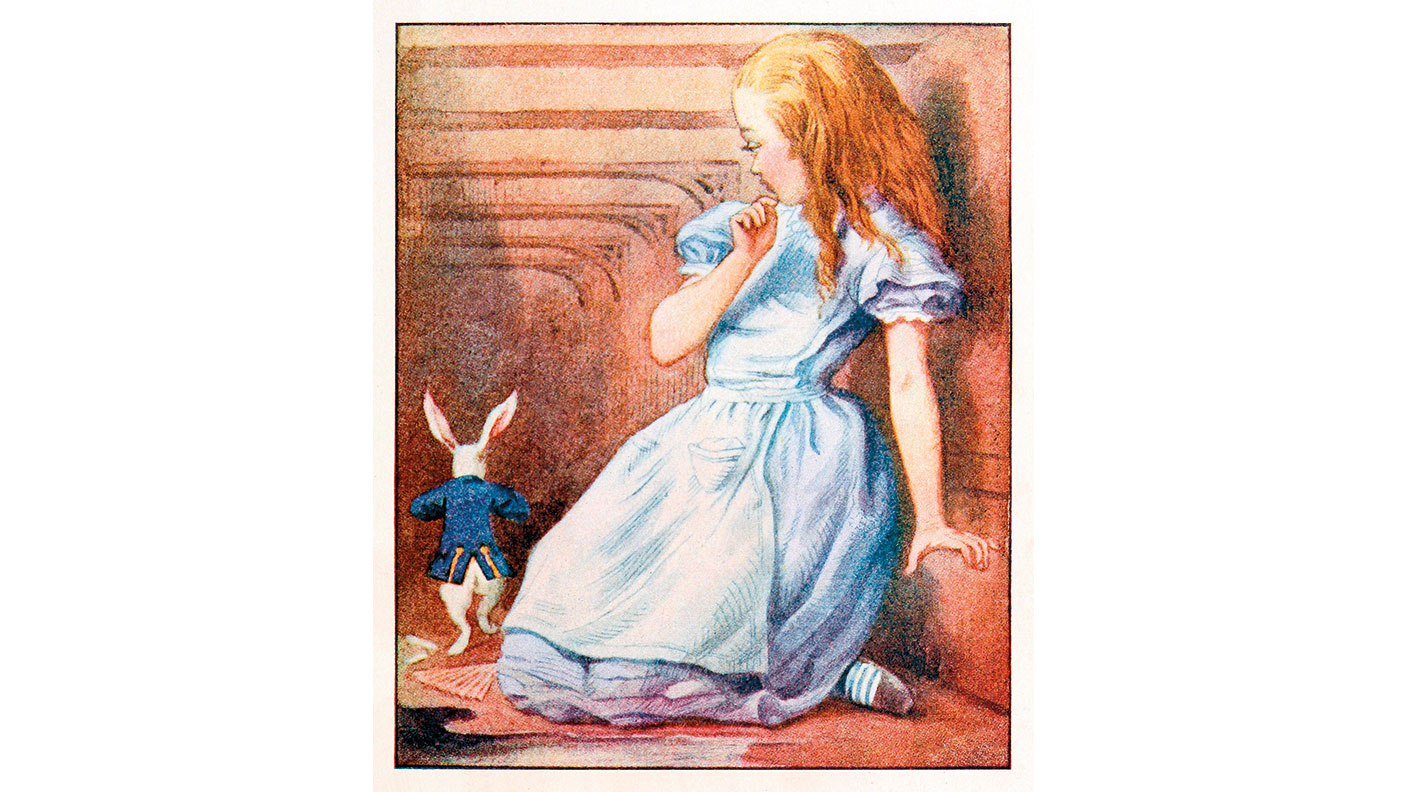

The global economy goes down a rabbit hole

Central banks have manipulated the price of money for years and turned markets upside down, says Edward Chancellor.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Alice’s first day at Tweedle Asset Management was going to be a busy one. She was escorted around the offices by a young staffer named Otto. Their first visit was to the bond team. Fixed income was Alice’s keenest interest. “Do you hold bonds for income?” she asked eagerly. Everyone laughed.

“Are you dreaming?” the desk head replied rudely. “The coupon is subtracted from the principal, not paid out. If it’s income you want, you should take out a Danish mortgage, they pay very well.”“But why own a bond, if it doesn’t pay interest?” Alice asked. “As long as yields continue declining, even at negative rates we hold bonds for capital gains. If you want dividends, go ask the equity folks.”

“I see,” said Alice doubtfully, hoping that stock-market investors would prove more sensible. At least they valued investments by discounting future income streams. But on opening a door marked “Fundamental Active Equity”, she came across an empty trading floor. “Oh, we closed down that team last month – they’d been underperforming for decades,” said Otto. “What was their problem – did they buy overpriced stocks?” “That’s exactly what they didn’t do!” replied Otto scornfully. “They stuck with value, and as everybody knows value sucks. If you want to outperform, you’ve got to show your FANGs.” This didn’t sound quite right to Alice.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Forget stocks – the real action is in unicorns

“Forget about equities,” Otto advised. “If you want to meet real investors, go visit the Venture Capital team.” So Alice did. “What type of companies do you invest in?” asked Alice of the young VC, named Anna. “We invest in unicorns,” replied Anna smartly. “That must be difficult, because unicorns are mythical creatures,” Alice joked.

“Well, there are hundreds of unicorns in Silicon Valley – a unicorn is just a company with a fabulous valuation. Still, the business side of affairs is pretty mythical,” she added with a smirk. “What do you mean?” asked Alice. “Well, most unicorns are just black boxes. If you open the box, it turns out to be empty.” “That doesn’t sound like a very wise investment,” said Alice. “True enough, but they make very good speculations. Besides our aim isn’t to find companies that do anything useful or will ever make a profit. No, we look to get in at an early funding stage and exit at the initial public offering. That’s where the real money is made.”

“If you set the clock – the tempo of capitalism – to run backwards the normal order breaks down”

Alice then visited the private-equity team, Tweedle’s highest-compensated employees. “How do you add value?” she asked to get the conversation going. “There are only three things you need to know about private equity: leverage, leverage and leverage,” replied a slick young man in a bespoke Savile Row suit.“Our business is financial engineering.”

“But isn’t it risky to load companies with too much debt?” “Oh, all the risk is carried by the creditors – we stuff them with covenant-lite loans, payment-in-kind bonds, and the like. They’ll take any trash for the tiniest slither of income. And when the proverbial hits the fan, we refinance.” “Everything seems so strange,” Alice thought to herself. “I don’t think I’m cut out to be an investor. Perhaps I’d enjoy economics research more.”

She soon found herself knocking on the door of Dr. Oirob, head of Tweedle’s monetary and economics department. “The highly abnormal is becoming uncomfortably normal,” intoned the doctor. “Interest rates have been pushed down to unimaginable levels. There is something vaguely troubling when the unthinkable becomes routine.” “At last, here’s someone I understand,” Alice mused.

The snake-oil peddlers

“Central banks have stepped through a mirror,” continued Oirob excitedly. “They used to struggle to control inflation. Now they can’t push it up. They used to oppose wage increases, now they urge them on. Everything is upside down.” Alice now wondered whether she understood any of this.

To change the subject she asked,“Isn’t Modern Monetary Theory the cure to all our problems?” Alice really was au courant with the latest trends in economics. “Why those snake-oil peddlers,” replied the sage, showing an irascible side, “would have us believe six impossible things before breakfast – government debt doesn’t matter, deficits are the cure not the problem, governments don’t have to raise taxes or issue bonds, they can just print money, blah, blah. It’s the most complete nonsense!”

“Here’s the root of the problem,” Oirob continued. “For two decades or more, central banks have played around with interest rates, pushing them lower and lower. They meant well, but didn’t understand they were messing with the price of time. If you set the clock – the tempo of capitalism – to run backwards the normal order of things breaks down: companies turn into zombies, herds of unicorns appear, investment discipline disappears. Wealth becomes virtual. Inequality is unleashed. Society melts down, markets melt up...”

At this point, Alice opened her eyes. It had all been a dream. Now, it was back to dull reality. She clicked on the Reuters website to see if anything had happened. Nothing remarkable, just a story about a new strain of the cold virus spreading in central China.

A longer version of this article was first published on breakingviews.com

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Edward specialises in business and finance and he regularly contributes to the MoneyWeek regarding the global economy during the pre, during and post-pandemic, plus he reports on the global stock market on occasion.

Edward has written for many reputable publications such as The New York Times, Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Yahoo, The Spectator and he is currently a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He is also a financial historian and investment strategist with a first-class honours degree from Trinity College, Cambridge.

Edward received a George Polk Award in 2008 for financial reporting for his article “Ponzi Nation” in Institutional Investor magazine. He is also a book writer, his latest book being The Price of Time, which was longlisted for the FT 2022 Business Book of the Year.

-

Hints of private credit crisis rattle investors

Hints of private credit crisis rattle investorsThere are similarities to 2007 in private credit. Investors shouldn’t panic, but they should be alert to the possibility of a crash.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

The scourge of youth unemployment in Britain

The scourge of youth unemployment in BritainYouth unemployment in Britain is the worst it’s been for more than a decade. Something dramatic seems to have changed in the labour markets. What is it?

-

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growth

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growthGDP doesn’t measure what we should care about, say critics. Is that true?

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again