Hong Kong’s crown slips as Singapore takes over

As international sentiment sours on Hong Kong, other Asian financial hubs – primarily Singapore – are snapping up business.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“Since Hong Kong’s return to the motherland in 1997, its financial market has evolved… with remarkable progress made in the banking system, capital market, as well as the foreign exchange market,” says Xinhua, China’s state news agency. Since July 1997 the value of the local stockmarket has grown from HK$4.6trn (£490bn) to HK$38trn (£4.04trn) today. The city was ranked third in the latest edition of the Global Financial Centres Index, behind only New York and London.

Yet international business is souring on Hong Kong, says the Financial Times. The territory still has strengths: “a convertible currency, a bustling port and mechanisms that allow international investors to gain exposure to the Chinese market”. But byzantine Covid-19 rules and the erosion of the rule of law mean that “since the start of the year, more than 130,000 people have left”. In the future “Hong Kong will be less international and closer to China, both economically and culturally”.

Travelling to Hong Kong “is now only for the determined” because of strict entry requirements and quarantine, says Elaine Yu in The Wall Street Journal. In 2019, 70 million passengers passed through its airport, but this figure had fallen 98% by last year. Bankers are looking elsewhere in Asia to network.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Singapore: Asia’s new number one

Other Asian financial hubs want to snap up business that’s leaving Hong Kong. But many have their own problems. South Korea’s reputation for poor regulation and high taxes has deterred financiers. Tokyo offers “political stability and good public security”, as well as “excellent education resources” for expatriates’ children, says Takeshi Kawasaki in Nikkei Asia. But Japan’s “complex and heavy tax system” is deterring many of the hedge funds relocating from Hong Kong. Unlike Hong Kong or Singapore, Japan also taxes capital gains, providing another “huge disincentive” to the finance industry.

“As China grows more authoritarian, the chances of Shanghai resuming its pre-1949 role as a global hub have receded,” says The Economist. Instead, Singapore looks best placed to capitalise on Hong Kong’s woes. The city-state boasts “an effective and predictable government” and its geopolitical neutrality “allows it to act as a hub for both Western and Chinese capital and businesses”. It also has “a reliable legal system and a business-friendly regulatory environment” – things that Hong Kong is losing.

“Simple laws for establishing trusts” saw Singapore surpass Hong Kong as a hub for regional wealth management in 2017, with $3.4trn of assets under management in 2020. Yet “when it comes to capital markets and investment banking”, Hong Kong remains top, with nearly $5trn of listed stocks compared with just $700bn in Singapore.

Hong Kong's diminishing importance to Beijing

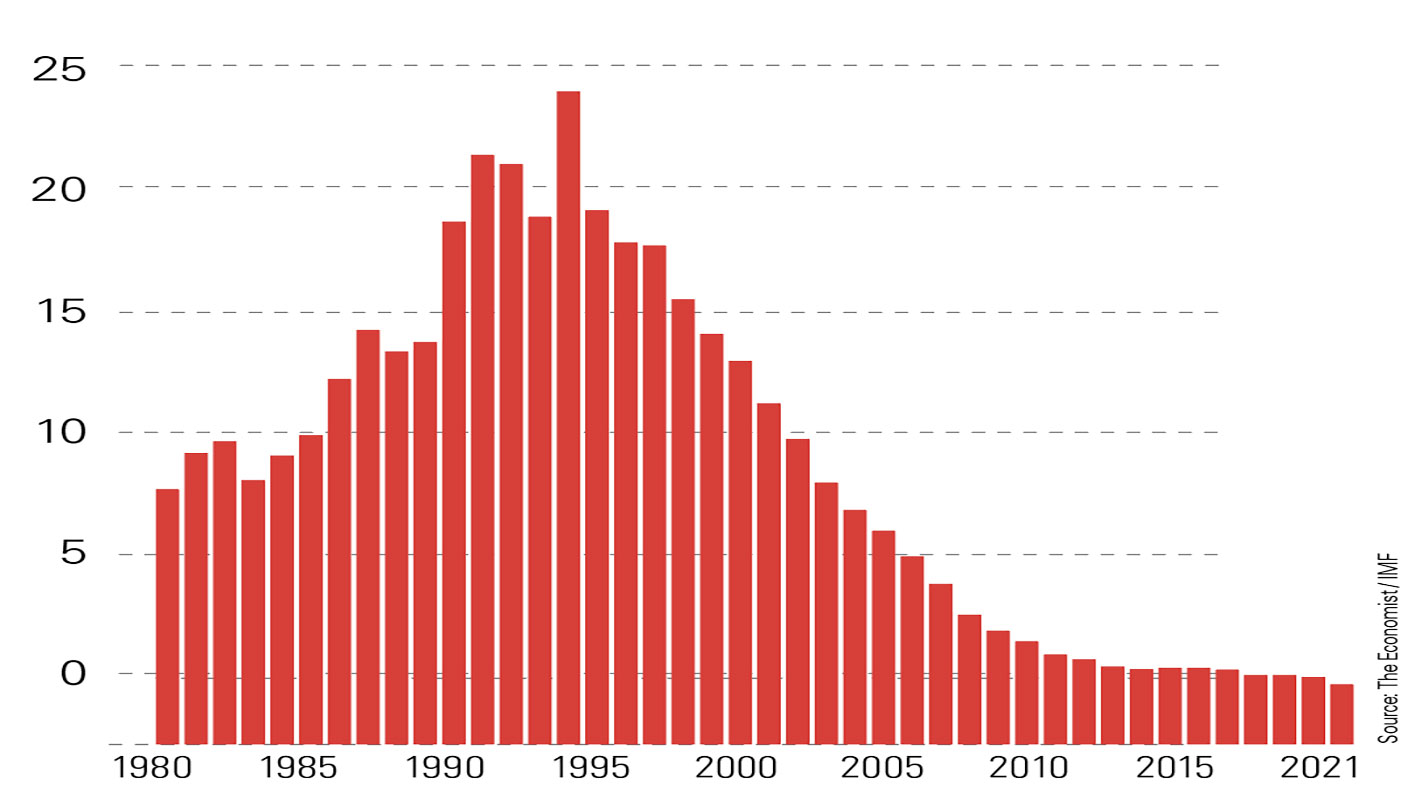

China’s crackdown in Hong Kong is a sign of the territory’s diminishing importance to Beijing. After the 1997 handover, Communist party cadres looked to Hong Kong as an important source of capital through which to fund China’s economic development. At the time of the handover Hong Kong’s economy was worth more than 18% of mainland China’s GDP.

Hong Kong’s GDP as a % of China’s

However, faster growth in China has since seen that percentage fall to just 2.1%, says Prableen Bajpai on Investopedia. Today China’s $17.33trn economy dwarfs Hong Kong’s $368.13bn (Hong Kong’s GDP per capita, at $49,660, remains far higher than the mainland’s $12,556, however). In 2021 mainland companies accounted for almost 79% of the Hong Kong market’s value.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alex is an investment writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2015. He has been the magazine’s markets editor since 2019.

Alex has a passion for demystifying the often arcane world of finance for a general readership. While financial media tends to focus compulsively on the latest trend, the best opportunities can lie forgotten elsewhere.

He is especially interested in European equities – where his fluent French helps him to cover the continent’s largest bourse – and emerging markets, where his experience living in Beijing, and conversational Chinese, prove useful.

Hailing from Leeds, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Oxford. He also holds a Master of Public Health from the University of Manchester.

-

The UK regions with the highest proportion of homes above the inheritance tax threshold

The UK regions with the highest proportion of homes above the inheritance tax thresholdHigh house prices are pushing more families into the inheritance tax trap across the country

-

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek Talks

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek TalksPodcast Clare Francis, savings and investments director at Barclays, speaks about money and mental health, why you should start investing, and how to build long-term financial resilience.

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.