How to profit from molybdenum

There is one metal that China has not yet cornered the market in: molybdenum, which makes steel resistant to corrosion and extreme heat. But China wants control of that, too. Eoin Gleeson examines the sector, and explains the best way to profit from molybdenum.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

China seems determined to own all the world's metals. There is one critical metal it has missed out on so far: molybdenum. But not for much longer.

Molybdenum has been vital to just about every infrastructure project the Chinese have undertaken. 'Moly' makes steel resistant to corrosion and extreme heat. So it is a vital ingredient in the high-strength steel China uses to build everything from cars to the skeleton structure of its skyscrapers. China was one of the primary producers of the metal in 2008, with exports of 25 million pounds. But this year it became a net importer for the first time, according to consultancy firm MolyEx. Why?

Lately it has just been too expensive to mine the stuff, says Chris Mayer in the DailyWealth newsletter. China is one of the few countries with deposits big enough to warrant extensive moly mining there are also substantial deposits in the US and Chile. But it costs nearly $13 to produce a pound of moly from Chinese mines, and moly trades at only $8 today down from its peak of $30/lb. The huge environmental cost of developing moly mines is shifting production from China to America.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

But that has done nothing to kill off China's demand for the metal. They may not be able to mine it, but the Chinese are importing huge quantities instead. In the first half of this year, 40% of Chilean moly exports were shipped to China there were no Chilean exports at all in the first half of 2008. And the Chinese recognise that they can stockpile the metal while it's cheap, knowing that it is critical to the energy industry.

Nuclear power utilities, for example, rely on super-resistant moly alloys to replace the world's ageing reactor condenser tubes. Each new reactor will need at least 400,000 pounds of the stuff. Around 100 new reactors are scheduled for construction in China over the next few years. America, meanwhile, is hoping to build twice that many.

Then there are the oil pipelines. The Alaskan pipeline consists of a moly alloy that can handle temperatures of 70F. Without moly, the 48-inch thick pipeline, which delivers 775,000 barrels of oil a day to the US, couldn't hope to maintain the 99% integrity it keeps along 800 miles of tundra.

A burst in steel production in the last few months has also boosted moly demand. The more steel going into cars, buildings and appliances, the more moly you need. That can't last for ever. Steel makers are heavily indebted to stimulus packages and are being a bit too enthusiastic about firing up dormant mills. Hot-rolled steel, a benchmark grade that is processed into cars, buildings and appliances, cost about $600 to $630 a tonne in August. But it can now be had for about $550 to $570 a ton, according to World Steel Dynamics. Steel makers appear to have stocked up for now on the necessary alloying metals for the quarter ahead. Nonetheless, a slew of big projects to develop primary moly mines have foundered for lack of finance this year (see below). So supply will remain tight.

Once demand for molybdenum picks up as oil pipelines are laid, nuclear plants are built and China continues its steel-intensive bid for industrialisation, it won't stay at $8 per pound for long. Chinese demand alone has been growing at 27% a year, making up a quarter of global demand. And true to form, Beijing has started banning exports and hoarding the stuff.

The best bet in the sector

Thompson Creek Metals (NYSE:TC) is one of the world's largest publicly traded producers of molybdenum. The group has four sites two in British Columbia, one in Idaho and one in Pennsylvania. Total mineral reserves exceed one billion pounds of moly excluding the potentially massive Mt Emmons deposit in Colorado.

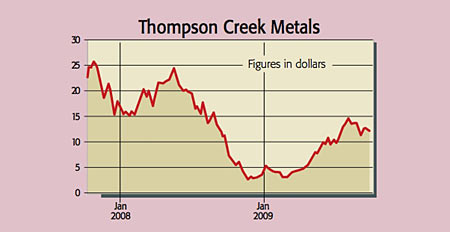

Thompson Creek Metals recently announced deal financing of C$217m to develop the Endako expansion in British Columbia. As of 30 June, the company had C$262m of cash and a debt load of C$16m. The firm suffered last year as the price of the metal dipped. But it is profitable and will rebound strongly as demand for moly in nuclear, steel and energy infrastructure projects picks up.

Meanwhile, major rival projects have been delayed this year. The New Big Hope project, owned by junior miner General Moly, is at least 20 months away, even once it gets financing, says Chris Mayer in the Daily Wealth newsletter. And other big projects by Freeport and Moly Mines have been pushed back to 2011. Thompson Creek Metals trades on an attractive forward p/e of 11.3.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Eoin came to MoneyWeek in 2006 having graduated with a MLitt in economics from Trinity College, Dublin. He taught economic history for two years at Trinity, while researching a thesis on how herd behaviour destroys financial markets.

-

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026Podcast Fidelity's Tom Stevenson reveals his top three funds for 2026 for your ISA or self-invested personal pension

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now