Global Economy

The latest news, updates and opinions on Global Economy from the expert team here at MoneyWeek

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

Canada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

By Simon Wilson Published

-

Why does Trump want Greenland?

The US wants to annex Greenland as it increasingly sees the world in terms of 19th-century Great Power politics and wants to secure crucial national interests

By Simon Wilson Published

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

The state of Iran’s economy – and why people are protesting

Iran has long been mired in an economic crisis that is part of a wider systemic failure. Do the protests show a way out?

By Simon Wilson Published

-

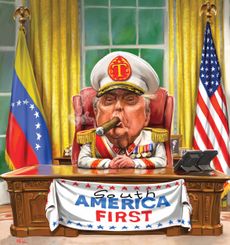

Why does Donald Trump want Venezuela's oil?

The US has seized control of Venezuelan oil. Why and to what end?

By Simon Wilson Published

-

My market predictions for 2026

Opinion My 2026 predictions, from a supermarket merger to Dubai introducing an income tax and Britain’s journey back to the 1970s

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

The war dividend: how to invest in defence stocks

Western governments are back on a war footing. Investors should be prepared, too, says Jamie Ward

By Jamie Ward Published

-

Did COP30 achieve anything to tackle climate change?

The COP30 summit was a failure. But the world is going green regardless, says Simon Wilson

By Simon Wilson Published

-

How to profit from defence stocks beyond Europe

Opinion Tom Bailey, head of research for the Future of Defence Indo-Pac ex-China UCITS ETF, picks three defence stocks where he'd put his money

By Tom Bailey Published

Opinion