Why Modi’s magic now looks like an illusion for investors in India

Investors are losing confidence in India’s prime minister and his promise of further reforms. The country’s potential remains intact, but be prepared for some short-term bumps, says Cris Sholto Heaton.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

When Narendra Modi won a landslide victory in India's general election in May, stocks quickly surged to a new high. Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are widely seen as more business-friendly than the opposition, and investors hoped that a larger majority would allow the prime minister to speed up the economic reforms that he promised when he won a first term in office in 2014.

Unfortunately, Modi's most decisive move since his re-election has prioritised a different side of his agenda. At the beginning of August, the government revoked the special constitutional status that applied to Jammu and Kashmir in northern India, which previously gave this state a degree of administrative autonomy. Although this was in the BJP's manifesto and has been a long-standing goal for the party, it was a controversial decision, since Jammu and Kashmir is an extremely sensitive region both domestically (it is India's only Muslim-majority state) and internationally (it lies on the border with Pakistan and China and includes several areas held by one country but claimed by another).

The area has problems that defy easy solutions including a long history of religious violence and abuses by the security services and require careful handling. So the government's decision to push ahead with this change reawakened fears about Modi's authoritarianism and his increasingly overt embrace of Hindu nationalism (an ideology that holds that India is the Hindu homeland and people of other faiths can live there only on sufferance).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

For non-partisans, there has always been a trade-off to having Modi in power: the expectation that his economic reforms will help India develop faster is set against doubts about the impact of his other views and policies on religious tolerance and stability. Serious questions about this go back almost two decades, to his controversial record as chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014. Supporters argue that his decisions there helped deliver strong growth in the state during his time in office, but critics say he was at least partly responsible for inflaming an appalling outbreak of violence between Hindus and Muslims in 2002 that left hundreds, possibly thousands, dead. The Jammu and Kashmir decision has reawakened these concerns about his judgement on social and religious issues, just as his economic competence is coming under greater scrutiny.

A very mixed record

For all the talk of India's recent success, the reality is Modi's economic achievements in the last few years are scanter than his supporters claim. On the plus side, there is the introduction of a new national goods and services tax a reform that is rather more totemic than it sounds, because it helps reduce some of the barriers to trade between states by doing away with a hotchpotch of different sales taxes and duties imposed by regional governments. A new bankruptcy code also aims to curb the problem of heavily indebted companies that continually fail to pay their creditors.

However, a decision to withdraw most large-denomination banknotes from circulation abruptly in 2016 was at best a bold idea badly executed it was intended help tackle corruption, tax evasion and counterfeiting, but caused huge disruption without ultimately achieving much. And outright negatives include weakening the independence of the Reserve Bank of India late last year in order to dip into its reserves to help fund public spending (and pay for some populist pledges ahead of the election) and to take the heat off some undercapitalised public-sector banks (and let them continue lending to politically important businesses).

Since the election, the government has announced welcome plans to change the country's restrictive employment laws, although it remains to be seen how ambitious these will be and how successful Modi will be in pushing them through in the face of inevitable strong opposition. This could be an important breakthrough, however: a radical shake-up would be the single most effective move the government could take to transform the manufacturing sector.

Set against that, the July budget was light on reform and heavy on new taxes and duties. These included a tax surcharge aimed at the wealthy that would have hit foreign institutional investors (FIIs) as well the measure has since been refined, but rattled FIIs still took $4bn out of Indian shares in the last two months, having invested $11bn in the first half of the year.

The growth illusion

There are also awkward questions about how well the economy has really performed in recent years. Officially, GDP has grown at 7% or more per year since 2011-2012. But this is at odds with other data, such as the sluggishness of business investment, and many analysts believe growth is being overestimated due to faults in a new method for calculating GDP. The true rate of growth may have been under 5%, according to a paper by Arvind Subramanian, formerly the country's chief economic adviser and now at Harvard University.

In any case, growth is now clearly slowing: at just 5% year-on-year officially, the latest quarter was the weakest result since early 2013, largely on the back of strains in consumer spending. This is at least partly due to ongoing problems in the non-banking financial company (NBFC) sector, India's shadow-banking industry. In recent years, these firms have supplied around one-third of new loans, especially to consumers, small business and housing but ever since IL&FS, a large infrastructure-focused NBFC, defaulted last year, investors have become more reluctant to lend to them. This in turn means that NBFCs have been unable to extend as many new loans, which has affected sectors such as automobiles and consumer durables, which depend on a steady flow of credit to finance purchases.

Economists are already starting to revise down forecasts for next year on the back of these trends, but some of the risks facing the global economy could well make matters worse. For example, India imports around 80% of its oil supply, so if this week's spike in the price of oil is sustained, it will increase the trade deficit and probably feed through into inflation and hurt domestic demand.

The case for India

Still, even if one doesn't think Modi and the BJP are doing a particularly good job of managing the country right now and even if India and the world in general may be approaching the end of the current economic cycle that doesn't demolish the long-term argument for investing there.

The core of the investment case is pretty simple. India has a vast population (over 1.3 billion, second only to China) and good demographics (the average age is 29). That creates an enormous potential market for growth for decades to come. There are no other countries in the world of that scale the next biggest emerging market is Indonesia, with around 270 million people and companies that can capitalise on the opportunity may grow to enormous scale.

Government decisions can certainly make matters better or worse and there are plenty of points on which to be pessimistic. The BJP's Hindu-nationalist policies risk making social unrest worse. Failure to change labour laws could mean that low-cost manufacturing never emerges as a route to bring large numbers of people into an modern industrial economy and so hundreds of millions could remain stuck in subsistence farming. There seems to be little immediate prospect of serious land reform, even though the experience of other emerging economies suggests that this could both strengthen the position of small farmers and reduce headaches for infrastructure, industry or housing developments (disputes over ownership makes land acquisition one of the biggest difficulties when doing business in India and often leads to major projects being abandoned altogether).

However, while it will be tragic if India fails to achieve its full potential and much of the population remains trapped in poverty, the country's sheer size means that even being partially successful will be a major economic shift. As such, it's a market that's impossible to ignore. The question is whether now is a good time to invest or whether the growing evidence that Modi is not the magician that investors hoped he would be, plus the wider headwinds facing most emerging markets at this point, make it particularly vulnerable to disappointment.

Expensive as ever

Certainly Indian stocks don't look like a bargain, even if the post-election blues have seen them retreat a little from their highs. The MSCI India index today trades on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of almost 23, compared with 13 for the MSCI Emerging Markets index. This comparison sounds slightly worse than the reality: the overall valuation of the MSCI EM is heavily affected by weightings towards markets such as China (with its superficially cheap but appalling banks) and Korea (with its highly cyclical manufacturing industries that trade on low valuations at the peak of the cycle). But it's still pricier than peers such as Indonesia (p/e of 17).

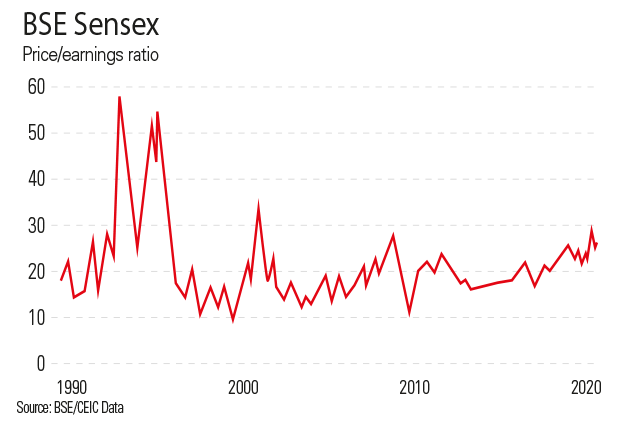

India has always been a relatively expensive market, as the chart shows. The long-term p/e ratio for the BSE Sensex (India's traditional domestic equity benchmark, with a longer history than the MSCI India) has been in the high teens or low 20s for most of the last two decades or so. Historically, this has been partly justified by the fact that India's biggest companies enjoy relatively good returns: average return on equity for Sensex firms has been near or above 20% for much of this time. Consequently long-term returns have been respectable: the Sensex (and the MSCI India) have returned around 10%-11% per year on average over the past 25 years.

However, valuations today are as high as they were at the peak of the market in 2000 or 2007 neither of which were good times to invest. Even if we wouldn't expect the market to plumb the single-digit p/es of 2008-2009 in a normal downturn, there's clearly scope for disappointment. To make matters worse, profitability is slipping: return on equity for Sensex firms was little more than 10% in 2018 (another bit of evidence that the economy has done less well in recent years than headline GDP numbers suggest).

The rupee rally runs out of steam

The currency is also a problem for foreign investors. The rupee has weakened steadily against the dollar over time, both under Modi and his predecessors, and hit an all-time low of almost 75 to the dollar in October last year. It rallied to 68 in the post-election euphoria, but has since slid again and now stands at around 72. This has a big impact on returns for overseas investors. The MSCI India has had an average total return of 6.3% per year over the last five years and 8.9% per year over the last ten years in rupee terms, but that falls to 2.9% per year and 4.9% per year respectively in US dollar terms. (The drag on returns for UK investors has been less extreme, since sterling has itself performed so badly against the dollar and most other major currencies.)

So it's difficult to be very optimistic about the near-term outlook for the Indian market. On the plus side, the economy is domestically driven and should be more insulated from a possible US-China trade spat than much of the emerging world. And there's little sign of any major internal crises brewing: the greatest risk is probably that the NBFC issues spread into the wider banking system. This could happen some banks, already coping with bad loans extended to troubled industrial groups in recent years, also have exposure to NBFCs that may turn sour but doesn't look like a systemic threat at present.

However, the combination of slow growth, disillusionment with Modi and the fact that the market is already richly valued could well send more investors heading for the exits especially FIIs, which tend to have a disproportionate impact on the direction of the market. So while MoneyWeek remains enthusiastic about India for the long term, this definitely feels like a time to take a comparatively cautious approach and my suggestions for what to buy and watch below reflect that.

Four ways to invest in India

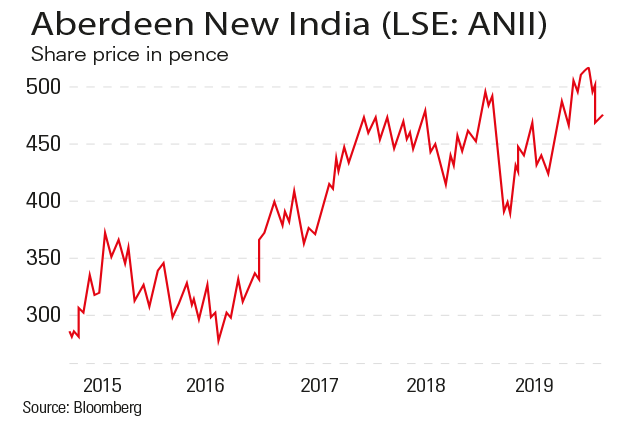

Aberdeen New India (LSE: NII) is MoneyWeek's preferred way to buy into the Indian market: not only does it have the best long-term record, but a clear focus on higher-quality companies should make it more defensive. The trust has an ongoing expense ratio of 1.17% and is on a discount to net asset value (NAV) of 13%.

The much larger JPMorgan India (LSE: JII) has performed similarly to Aberdeen New India over the past five years, with Aberdeen having a slight edge. However, while many of the funds' holdings overlap, there are significant differences in their sector weightings: JII has a lot more in financials (41% versus 26%) and less in consumer staples and information technology. This may make it more vulnerable if the economy weakens, as even relatively well-run banks willsuffer some pain. The ongoing charge is 1.09% and the discount to NAV is 9%.

India Capital Growth (LSE: IGC) has been more volatile. Until early 2018, it was outperforming by a large distance, but since then performance has slipped in a more difficult market. This is not entirely surprising since it focuses on mid-caps and smaller companies, but it has also been exposed to the NBFC crisis, through holdings such as Dewan Housing Finance (which it has now sold) and Yes Bank (whose share price has slumped amid concerns over its loans to shadow banks and other troubled borrowers).

The trust's discount of 20% may now look tempting, but the type of investments it favours look likely to keep underperforming at this stage of the cycle. The ongoing charge last year was 1.99%, although it has announced a 0.25 percentage point cut to the management fee.

Some other emerging-market funds are also heavily invested in India, including Fundsmith Emerging Equity (LSE: FEET). This has 40% of the portfolio there mostly in consumer goods and healthcare stocks that I like as long-term investments. Unlike the very successful Fundsmith Equity strategy, which invests in developed-market stocks, this has lagged its benchmark market since launch. The fund has now slipped to a discount to NAV of 10%, but I'd want to see more evidence that the managers have tackled the reasons for its weak returns so far before buying. The ongoing charge last year was 1.4%, with the management fee cut by 0.25 percentage points this year.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson

-

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fire

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fireIndian stocks pass a new milestone, but global fund managers are holding back. Are there signs of overheating?

-

Invest in space: the final frontier for investors

Invest in space: the final frontier for investorsCover Story Matthew Partridge takes a look at how to invest in space, and explores the top stocks to buy to build exposure to this rapidly expanding sector.

-

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growth

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growthCover Story It’s time to invest in Brazil as the economic powerhouse looks set to profit from the two key trends of the next 20 years: the global energy transition and population growth, says James McKeigue.

-

Shining a light on India

Shining a light on IndiaAdvertisement Feature Despite some short-term challenges, India remains very attractive for investors. Here’s why.

-

5 of the world’s best stocks

5 of the world’s best stocksCover Story Here are five of the world’s best stocks according to Rupert Hargreaves. He believes all of these businesses have unique advantages that will help them grow.

-

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sector

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sectorCover Story Move over, Silicon Valley. Over the past two decades the UK has become one of the main global hubs for tech start-ups. Matthew Partridge explains why, and highlights the most promising investments.

-

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?Cover Story Gold has always been the most reliable form of money. Now collaboration between China and Russia could lead to a new gold-backed means of exchange – giving prices a big boost, says Dominic Frisby

-

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?Briefings India has come a long way since independence to become the world's fifth-largest economy. But early mistakes and now a divisive leader are holding back the economy’s potential.